If you’ve ever scrolled through Zillow and paused on a listing for a house from the 1800s, you’ve probably felt that pull. The wraparound porch. The wavy glass. That weird, inexplicable feeling that the walls have actual stories to tell. Honestly, it’s a vibe. But let’s be real for a second—buying a home built in the 19th century isn’t just about aesthetics or pretending you’re in a period drama. It’s a lifestyle choice that involves a lot of dust, some very confusing plumbing, and a steep learning curve.

Old houses are stubborn. They don't care about your smart thermostat or your desire for perfectly level floors. They were built before power tools, before standardized lumber, and long before the concept of an "open floor plan" existed. Back then, rooms were small for a reason: heat was a luxury. You closed the door to keep the warmth from the fireplace in the room with you.

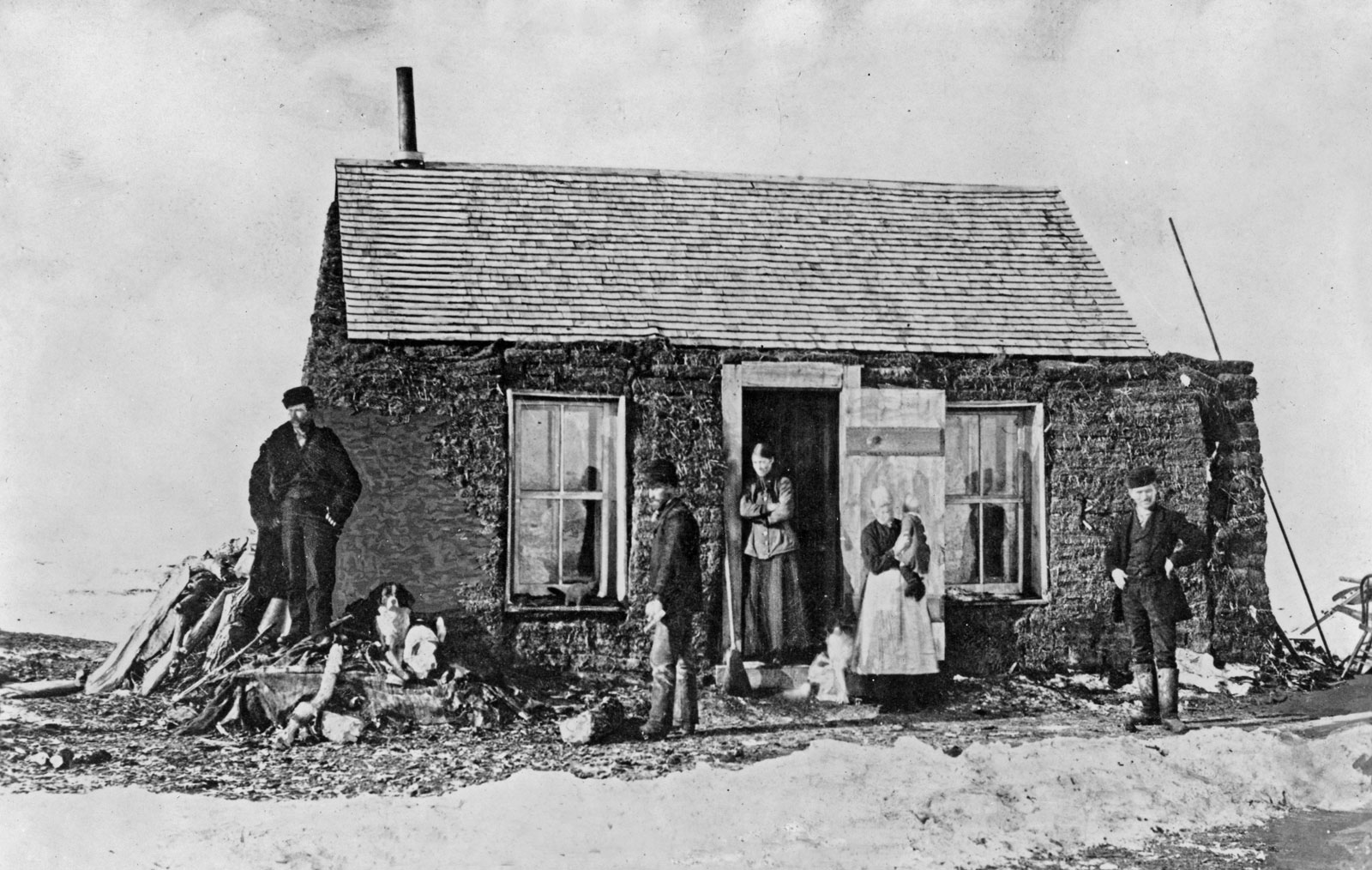

The Reality of 19th-Century Construction

When we talk about a house from the 1800s, we are looking at a massive range of styles. In the early 1800s, Federal-style homes were all about symmetry and understated elegance. By the mid-century, the Gothic Revival brought those pointy arches and "gingerbread" trim. Then came the Victorians—Queen Annes with their towers and Italianates with their bracketed eaves.

The craftsmanship is what usually gets people. You won't find hand-hewn beams in a modern suburban development. Builders back then used "old-growth" timber. This wood is incredibly dense compared to the soft, fast-grown pine we use today. It’s why an 1850s farmhouse can still be standing straight while a 1990s build is already sagging.

But there’s a trade-off.

The "bones" might be solid, but the systems are usually a mess. Unless a previous owner did a full "to-the-studs" renovation, you’re likely looking at a mix of eras. You might have some original gas lines that were capped off in the 1920s, some knob-and-tube wiring from the 1940s, and maybe some questionable PVC plumbing from the 70s. It’s a puzzle. A very expensive, potentially sparking puzzle.

📖 Related: Defining Chic: Why It Is Not Just About the Clothes You Wear

That Wavy Glass Mystery

Have you ever looked through an old window and felt like you were underwater? People used to think the glass was "melting" over time because it’s thicker at the bottom. That’s actually a myth. It’s just how cylinder glass was made. Glassblowers would create a giant cylinder of glass, cut it, and flatten it out. It wasn't perfect. It had ripples, bubbles (called "seeds"), and streaks.

Keeping those original windows is a point of pride for many old house owners. Modern double-pane windows might be more energy-efficient for a few years, but once the seal breaks, they’re trash. An 1880s sash window? You can repair that forever. You just need some glazing putty and a lot of patience.

Why a House from the 1800s Smells Like That

It’s not just "old person" smell. It’s the smell of horsehair plaster, damp basement stone, and decades of woodsmoke trapped in the floorboards. Plaster walls are a huge part of the 19th-century experience. Before drywall became the standard after WWII, walls were made by nailing thin wooden strips (lath) to the studs and smearing layers of lime plaster over them.

Plaster is a superior material. It’s thicker, it’s a better sound insulator, and it has a certain "softness" to its look that drywall can't replicate. But it cracks. As the house settles over 150 years—and it will settle—those cracks spider-web across the ceiling. Fixing it properly is an art form that’s slowly dying out. Most modern contractors will just tell you to rip it out and put up blueboard. Don't listen to them. If you can save the plaster, save the plaster.

The Foundation and the "Scary" Basement

Most people head straight for the kitchen during a showing, but you should head for the cellar. In a house from the 1800s, you aren't going to find a poured concrete basement. You’re going to find a fieldstone foundation or maybe brick.

👉 See also: Deep Wave Short Hair Styles: Why Your Texture Might Be Failing You

- Fieldstone: Big rocks held together with lime mortar.

- The Floor: Often just dirt or a thin "rat slab" of old concrete.

- Moisture: It's going to be damp. These foundations were designed to breathe.

- The "Summer Kitchen": Sometimes you'll find a massive fireplace in the basement where the cooking happened in the heat of July.

If you see white, fuzzy stuff on the stones, that’s efflorescence—basically salt deposits left behind by water. It’s common. But if you see the mortar crumbling into sand (spalling), you’ve got work to do. You can’t just use modern Portland cement to fix a lime mortar foundation. The modern stuff is too hard; it won't allow the stones to shift and breathe, which actually causes the old stones to crack. You have to use lime-based mortar. This is the kind of specific, slightly annoying knowledge you have to acquire when you own a piece of history.

Layout Quirks You Didn't Expect

Living in an old house means accepting that the layout was designed for a completely different way of life. There are no walk-in closets. People didn't have fifty pairs of shoes in 1840. They had a wardrobe or an armoire. If there is a closet, it’s probably under a staircase and roughly the size of a microwave.

Then there’s the "death stairs."

That’s what many owners call the back staircase. They are steep, narrow, and have treads that barely fit a human foot. These were often for servants or just a secondary way to get to the bedrooms. They are terrifying at 2 AM.

And bathrooms? Forget about it. Indoor plumbing didn't become a standard feature until the late 1800s or even the early 1900s for rural areas. This means that the bathroom in your house from the 1800s was probably a bedroom or a large closet at some point. That’s why the plumbing often looks like it was "tacked on"—because it was.

✨ Don't miss: December 12 Birthdays: What the Sagittarius-Capricorn Cusp Really Means for Success

The Maintenance Debt

You don't really "own" a house from this era. You're more like a glorified caretaker. The term "deferred maintenance" will become your new nightmare. If a previous owner ignored a roof leak in 1984, you're the one dealing with the rotted joists today.

Lead paint is a reality. Asbestos around the old gravity furnace pipes is a reality. These aren't dealbreakers, but they require a "safety first" mindset. You can't just go sanding down the trim without a HEPA vacuum and a respirator.

The Cost of Authenticity

Is it more expensive to live in a house from the 1800s? Usually, yeah. Your heating bills will be higher because even with insulation, these houses are drafty. Custom-cutting trim to match a 150-year-old profile costs way more than buying a piece of MDF from a big-box store.

But then you see the sunlight hitting the original wide-plank pumpkin pine floors. You see the hand-carved newel post at the bottom of the stairs. You realize that your house has survived hurricanes, civil wars, and the invention of the automobile. There is a weight to that. A sense of permanence that a new build just can't offer.

Practical Steps for Prospective Owners

If you're serious about buying or restoring an 1800s home, don't just wing it. It's a specialized field.

- Find a Specialist Inspector: Do not hire a guy who mostly inspects new condos. You need someone who knows what a sills plate is and can recognize if a 150-year-old beam has powderpost beetle damage.

- Join the "Old House" Community: Sites like The Craftsman Blog or the Old House Guy offer deep dives into historically accurate repairs. There are also massive Facebook groups dedicated to "The Money Pit" lifestyle where you can get advice on everything from unsticking painted windows to sourcing salvaged hardware.

- Prioritize the Envelope: Before you buy that vintage-style stove, fix the roof and the gutters. Water is the number one enemy of an old house. If you keep the water out, the house will last another 200 years.

- Audit the Electrical: If you see ceramic knobs on your attic joists with wires running through them, call an electrician. Knob-and-tube is not inherently evil, but most insurance companies hate it, and it wasn't designed for the load of a modern kitchen.

- Learn to DIY Small Things: You will go broke if you call a pro for every squeaky floorboard or cracked pane of glass. Buy a good set of scrapers, a heat gun (for lead-safe paint removal), and a book on basic home repair.

Owning a house from the 1800s is a labor of love, emphasis on the labor. It's a hobby that you happen to live inside. If you want perfection, buy a new build. But if you want a home with a soul—and you don't mind a few drafts—there’s nothing else like it.

Actionable Insight: Start your journey by visiting the National Register of Historic Places database to research the architectural history of your specific region. This helps you identify which local materials and styles are authentic to your area before you begin any restoration work.