It starts with a drop of blood. Just one. Most people remember the giant, foul-mouthed plant from the movie, but if you really want to understand the soul of this show, you have to look at the moment it all goes wrong. I’m talking about Little Shop of Horrors Grow For Me, the song that basically functions as the "inciting incident" for the entire botanical nightmare. It’s a desperate, nerdy plea from a guy who just wants to be noticed, and it’s arguably one of the most clever pieces of musical theater writing ever put to paper by Alan Menken and Howard Ashman.

Seymour Krelborn is stuck. He’s living in a basement on Skid Row. He’s in love with a girl who thinks she deserves to be treated like garbage. And he’s got this weird plant that won't stop dying.

The Desperation Behind Little Shop of Horrors Grow For Me

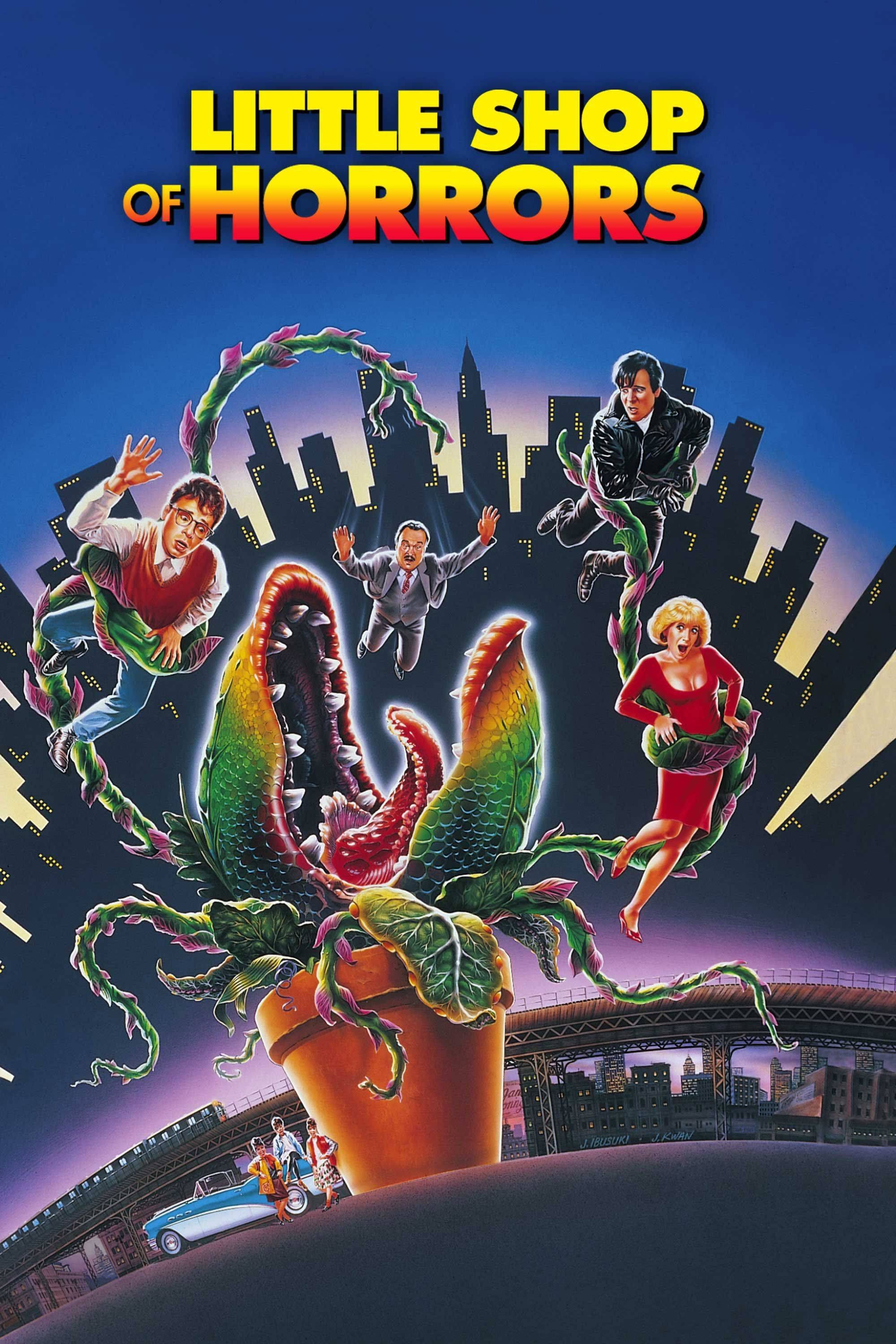

You’ve probably seen the 1986 Rick Moranis film, or maybe you caught a local community theater production where the plant looked like a spray-painted sock. Regardless of the budget, the song "Grow For Me" hits the same. It’s a solo. It’s awkward. Seymour is literally begging a vegetable to thrive so he can keep his job and maybe get the girl.

The song starts out as a sweet, almost 1950s-style doo-wop ballad. It’s got that classic Menken lilt. But the lyrics are where Ashman’s genius shines. He captures the specific kind of frantic anxiety that comes with being a failure. Seymour has tried everything. He’s tried plant food. He’s tried different amounts of water. He’s tried "mineral supplements" and "N-P-K" ratios (that's nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium for the non-gardeners out there).

Nothing works.

Then he pricks his finger on a rose thorn.

The shift in the music when the plant—Audrey II—reacts to the blood is subtle at first. But for the audience, it’s the "oh no" moment. We watch a man decide, in real-time, that his own physical safety is less important than his professional success. Honestly, it’s a little too relatable for anyone who has ever over-worked themselves for a paycheck.

What Howard Ashman Was Actually Doing

A lot of folks think Little Shop is just a campy B-movie homage. It’s not. Or well, it is, but it’s also a deeply cynical commentary on the American Dream. Howard Ashman, who wrote the book and lyrics, was obsessed with the idea of "the monster within."

When Seymour sings Little Shop of Horrors Grow For Me, he isn't just feeding a plant. He’s making a pact. In the original 1982 Off-Broadway production at the Orpheum Theatre, this moment was much grittier than the polished movie version. Lee Wilkof, the original Seymour, played it with a layer of sweaty desperation that made the eventual murders feel almost inevitable.

📖 Related: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

The song serves a specific structural purpose:

- It establishes Seymour's technical knowledge (he’s actually a good botanist, just unlucky).

- It highlights his isolation (he’s talking to a pot of dirt).

- It introduces the "blood for success" motif.

- It sets the "Faustian bargain" in motion.

If Seymour doesn't bleed here, the story ends in twenty minutes with him being fired by Mushnik. The stakes are everything.

The Technical Difficulty of Performing the Song

If you’ve ever tried to sing this at karaoke or for an audition, you know it’s a trap. It sounds easy. It’s not. The vocal range required isn't insane, but the character work is. You have to be charming enough that the audience likes you, but pathetic enough that we understand why you’d feed your boss to a giant flytrap later.

Music directors often point to the "bridge" of the song as the hardest part to nail. Seymour lists off all the things he’s done for the plant. The tempo speeds up. The pitch rises. He’s spiraling. By the time he reaches the final "Grow for me!" he’s practically screaming at the ceiling.

Then there’s the puppetry. In a professional production, the "Phase 1" Audrey II is usually a hand puppet operated by the actor playing Seymour. You’re singing a complex, syncopated song while trying to make a hand puppet look like it’s subtly sniffing for blood. It’s a coordination nightmare. I once talked to a stage manager who said the biggest fear during this number isn't a missed note—it's the puppet's head falling off because the actor's hand got too sweaty.

Why the 1986 Movie Changed the Vibe

Frank Oz, the legendary puppeteer and director, had a very specific vision for the film. In the movie, the Little Shop of Horrors Grow For Me sequence is much more "cinematic." We get close-ups of Rick Moranis’s face. We see the lush colors of the flower shop.

But some purists argue the movie loses the claustrophobia of the stage. On stage, Seymour is trapped in a tiny shop with no escape. In the film, it feels a bit more like a whimsical fairy tale gone wrong. Both are great, but the stage version feels more dangerous. When Seymour realizes the plant wants blood, the silence in a live theater is deafening.

The Science of Seymour’s Struggle (Sorta)

Okay, let's talk about the botany for a second. Seymour mentions "Light and water / And carbon dioxide." This is basic photosynthesis. But then he gets into the weeds. He mentions he's tried "the floor," "the shelf," and "the backroom."

👉 See also: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

In reality, most plants that look like Audrey II (which was modeled after a mix of a Venus Flytrap and a pitcher plant) are incredibly finicky. Venus Flytraps (Dionaea muscipula) actually need nutrient-poor soil and distilled water. If you gave them "plant food" like Seymour suggests, you’d actually kill them. They evolved to eat insects specifically because their soil lacks nitrogen.

Seymour’s "blood" solution is actually scientifically sound in a morbid way. Blood is rich in iron and nitrogen. If you were a mad scientist trying to grow a sentient, alien plant, blood is actually a pretty high-quality fertilizer. It’s just, you know, morally questionable.

Cultural Legacy and the "Meme-ification" of the Song

In the last few years, especially on TikTok and Instagram, "Grow For Me" has found a second life. Gardeners use the audio to show off their failing house plants. It’s become a shorthand for the frustration of trying to keep a Fiddle Leaf Fig alive.

But beneath the memes, the song remains a powerhouse of musical storytelling. It’s the moment the protagonist stops being a victim of his environment and starts becoming an active participant in his own destruction.

We see this same trope in things like Breaking Bad or Macbeth. The hero finds a "shortcut" to power. The shortcut requires a small sacrifice. They tell themselves it’s just this one time. But the plant always gets bigger. And it always gets hungrier.

Breaking Down the Lyrics

If we look at the lines "I've given you sunshine / I've given you dirt," we see the simplicity of Seymour’s world. He thinks life is a series of inputs and outputs. If he does the "right" things, he should get the "right" results.

The tragedy of skid row is that the rules don't apply. Hard work doesn't get you out. Only something "strange and unusual" can change your life. That’s why the total eclipse of the sun is so important. It’s the supernatural breaking into a mundane, depressing reality.

Key takeaway from the lyrics:

✨ Don't miss: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

- Seymour is a scientist at heart, but a desperate man in practice.

- The plant is a "silent" character during this song, but its movements dictate the tempo.

- The transition from "Please" to "You've got to!" shows the shift from hope to demand.

How to Approach This Song Today

If you’re a performer or a fan, the best way to appreciate "Grow For Me" is to lean into the discomfort. It shouldn't be a pretty song. It should be a little bit gross. Seymour is literally rubbing blood onto a leaf.

When Christian Borle played Orin Scrivello (the dentist) in the recent Off-Broadway revival, people were reminded of how dark this show actually is. But Jonathan Groff’s Seymour reminded everyone of the heart. During his rendition of "Grow For Me," you didn't see a killer. You saw a kid who was tired of being invisible.

That’s the secret sauce. You have to love Seymour even while he’s doing something terrible.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Performers

If you're looking to dive deeper into the world of Audrey II or perhaps prepare for a production yourself, keep these specific points in mind:

- Study the 1960 Corman Film: To understand the vibe, watch the original non-musical movie. It’s public domain and totally wild. It gives context to the "Skid Row" desperation that the song draws from.

- Focus on the Dissonance: When singing or listening, notice the contrast between the upbeat melody and the increasingly dark lyrics. That tension is where the "Little Shop" magic happens.

- Puppetry Timing: If you're staging this, the plant shouldn't move too much. It should only react when the blood appears. It makes the "payoff" much stronger.

- Listen to the Cast Recordings: Compare the 1982 Off-Broadway recording (Lee Wilkof) with the 2003 Broadway version (Hunter Foster) and the 2019 Revival (Jonathan Groff). You'll hear three completely different takes on Seymour’s psyche.

The real power of Little Shop of Horrors Grow For Me isn't just the catchy tune. It's the universal feeling of standing over something you've put your heart into and realizing it might just need a little bit more than you’re able to give. Usually, that’s just more time or money. For Seymour, it was a pint of O-negative.

Next Steps for the Ultimate Fan

To truly master the nuances of this era of musical theater, your next move should be exploring the Howard Ashman demo tapes. There are rare recordings of Ashman himself singing "Grow For Me" while developing the show. Hearing the lyricist's original "voice" for Seymour reveals a much more neurotic, fast-talking character than the versions we usually see today. It changes how you perceive the rhythm of the entire opening act.

Furthermore, look into the "lost" ending of the 1986 film. Originally, the movie followed the stage play where Audrey II wins and takes over the world. Watching that alternative footage while keeping the lyrics of "Grow For Me" in mind reframes the song as a global threat rather than a personal mishap. It turns a small song about a plant into an anthem for the end of the world.