Forget the dusty, sepia-toned images of stone-faced men in top hats for a second. If you really want to understand what happened during the Industrial Revolution, you have to stop thinking of it as a boring list of inventions like the steam engine or the spinning jenny. It was chaos. Total, messy, loud, and often smelly chaos. It was the moment humanity basically decided to trade the rhythm of the sun for the rhythm of the clock, and honestly, we’re still dealing with the fallout of that breakup today.

Imagine living in a world where "on time" didn't really exist. Before the late 1700s, if you lived in a village, you worked when there was light. You slept when there wasn't. Then, suddenly, James Watt perfects the steam engine in 1776, and everything hits the fan. Factories started popping up in places like Manchester and Birmingham, and they didn't care if it was 2 AM or 2 PM. The machine was hungry. It needed to be fed coal and labor. This shift wasn't just a "technological advancement." It was a complete rewiring of the human brain.

The Great Stink and the Reality of the Urban Crush

People flocked to cities. Why? Because the money was there, or at least the promise of it. But the infrastructure was a joke. In London, the population exploded so fast that the city literally couldn't handle the waste. This led to the "Great Stink" of 1858. The Thames was essentially an open sewer. It got so bad that Parliament had to soak their curtains in chloride of lime just to tolerate being in the building.

Life during the Industrial Revolution meant living in "back-to-back" houses. These were tiny, cramped dwellings sharing three out of four walls with other houses. No ventilation. No indoor plumbing. Just a lot of people, a lot of soot, and a whole lot of cholera. Dr. John Snow—not the guy from Game of Thrones, but the actual physician—eventually figured out that cholera was waterborne by tracking an outbreak to a single water pump on Broad Street in 1854. Before that, everyone thought "miasma" or bad air was the killer. It's wild to think that we were building massive iron bridges and complex looms before we even understood that drinking poop-water was bad for us.

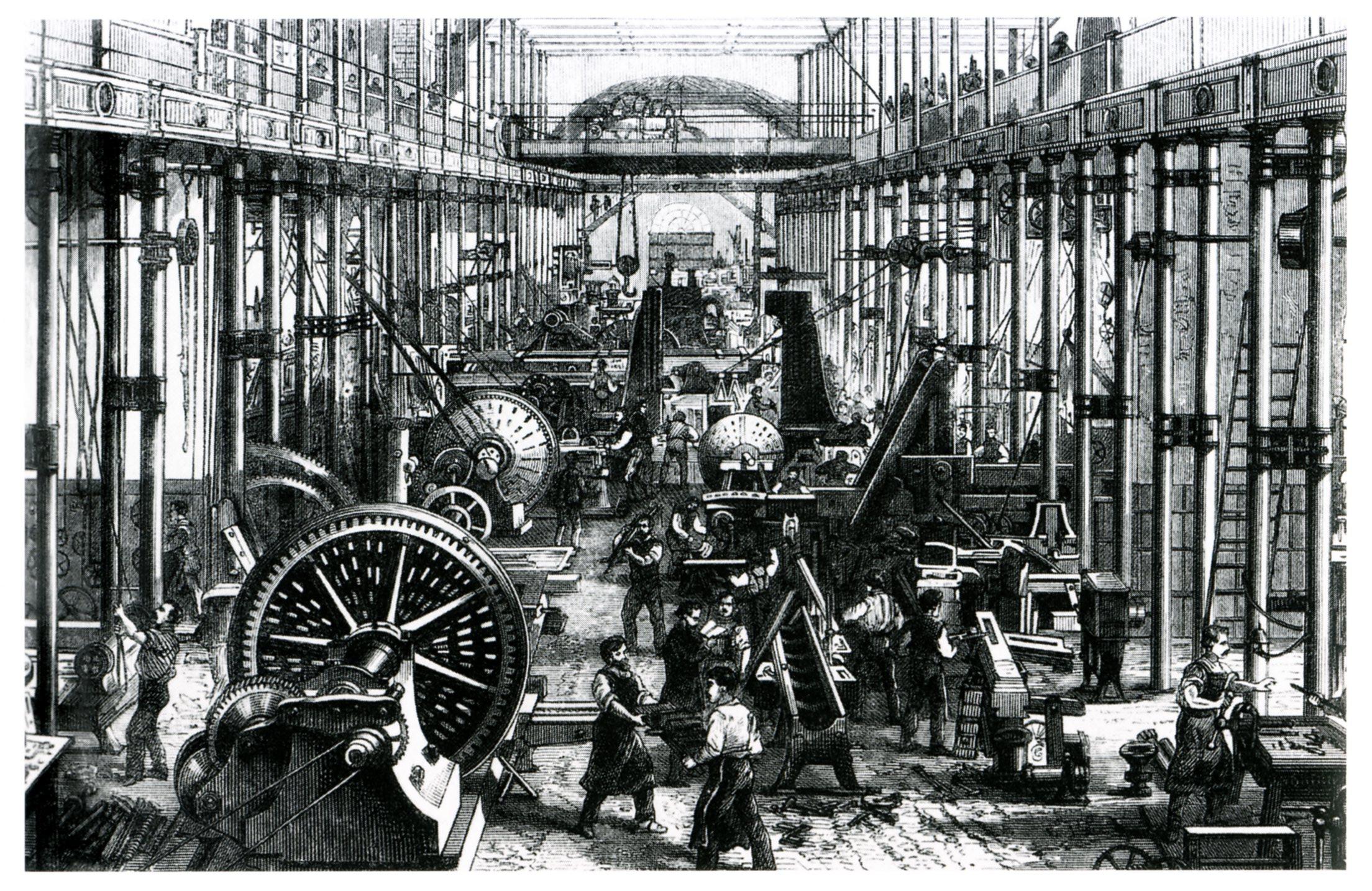

The Machines That Ate the World

We always talk about the "winners" of this era. The Carnegies. The Rockefellers. The Watts. But for the average person, technology felt more like a threat than a gift.

Take the Luddites. In modern slang, we call someone a Luddite if they can’t figure out how to use an iPhone. But the real Luddites, led by the mythical (and probably fictional) Ned Ludd, weren't tech-illiterate. They were highly skilled weavers. They saw that power looms were going to produce lower-quality fabric at a higher speed, effectively nuking their livelihoods. So, they did what any rational person would do: they grabbed giant hammers and started smashing the machines.

🔗 Read more: Why the Star Trek Flip Phone Still Defines How We Think About Gadgets

The government didn't take this lightly. By 1812, breaking a machine was a capital offense. You could literally be executed for sabotage. This tension between "efficiency" and "human dignity" is the central theme of the 19th century.

Child Labor: Not Just a Dickens Trope

It's uncomfortable to talk about, but the economic engine of the 1800s was fueled by children. They were small. They could crawl under moving machinery to clear jams or tie broken threads. In 1833, the Factory Act finally started to put some guardrails on this, but even then, it only "limited" children aged 9–13 to 48 hours of work a week. Imagine a 10-year-old working an eight-hour shift and thinking, "Wow, this is a huge improvement."

The "scavengers" and "piecers" in cotton mills faced horrific conditions. If they fell asleep or slowed down, they risked losing a limb to the belts and gears. This wasn't some niche occurrence; it was the standard operating procedure for decades. It took decades of activism from people like Lord Shaftesbury to move the needle on human rights.

The Birth of the Middle Class and the Weekend

It wasn't all misery, though. That's a common misconception. During the Industrial Revolution, we saw the rise of something brand new: the middle class. Before this, you were either a peasant or an aristocrat. Suddenly, there's a need for clerks, managers, engineers, and shopkeepers.

This new group had a little bit of extra cash. They wanted to buy things. This "consumer revolution" is why we have department stores today. It’s why Josiah Wedgwood became a household name—he figured out how to mass-produce fancy-looking pottery so middle-class families could feel a bit more posh.

💡 You might also like: Meta Quest 3 Bundle: What Most People Get Wrong

And let's talk about the weekend. "Saint Monday" was a tradition where workers would just... not show up on Monday because they were hungover or wanted an extra day off. Factory owners hated this. To combat it, they eventually struck a deal: if you work hard all week, you get Saturday afternoon and Sunday off. This compromise basically invented the modern weekend and, by extension, professional sports. Why do you think so many English football clubs were founded in the late 1800s? Because workers finally had a few hours on a Saturday to actually go watch a game.

Lighting Up the Night

Gas lighting changed everything. Before gas, when the sun went down, you were done. Maybe you had a dim candle or an oil lamp, but you weren't doing much. By the 1820s, London streets started to glow. This extended the workday, sure, but it also birthed the nightlife. Theaters, pubs, and shops could stay open. It made the city feel safer, even if the "safety" was mostly an illusion.

It also changed how we slept. Humans used to have a "biphasic" sleep pattern—you’d sleep for a few hours, wake up for an hour or two to read or chat, and then go back to sleep. The artificial light of the Industrial Age squeezed those two sleeps into one solid block. We literally changed our biology to fit the industrial schedule.

Environmental Scars and Global Impact

You can't talk about this period without mentioning the environment. The smog in cities like St. Louis or Pittsburgh (later on) or Manchester was so thick it was called "pea soup." It wasn't just fog; it was a toxic mix of soot and sulfur dioxide.

- The Carbon Spike: This is when the Keeling Curve—the graph showing the rise of CO2 in the atmosphere—really starts its upward climb.

- Deforestation: Entire forests were cleared to make room for factories or to provide timber for the massive expansion of the railways.

- Species Shift: The famous case of the peppered moth is a perfect example. Before the revolution, light-colored moths were common because they blended in with trees. As soot blackened the bark, dark-colored moths survived better. It’s evolution in real-time, powered by coal smoke.

Why Should You Care Today?

Everything you're doing right now—reading this on a screen, sitting in a climate-controlled room, maybe wearing clothes made in a factory halfway across the world—is a direct result of the shifts that happened during the Industrial Revolution.

📖 Related: Is Duo Dead? The Truth About Google’s Messy App Mergers

We are currently in what many call the "Fourth Industrial Revolution" (AI, biotech, etc.). The parallels are kind of scary. Just like the Luddites feared the power loom, people today fear automation and LLMs. The lesson from history isn't that we should stop the machines; it's that we usually fail to think about the human cost until the "Great Stink" happens.

If you want to dive deeper into this, don't just read textbooks. Look at the primary sources.

Next Steps for the History-Curious:

1. Read "The Condition of the Working Class in England" by Friedrich Engels. Before he became the co-author of the Communist Manifesto, Engels was sent by his father to manage a mill in Manchester. His firsthand accounts of the slums are harrowing and offer a perspective you won't get from a corporate history of the era.

2. Explore the Broad Street Pump map. Look up the original maps created by John Snow. It is a masterclass in data visualization and shows exactly how the intersection of technology (the pump) and lack of infrastructure (the sewage) created a catastrophe.

3. Visit a "Living History" Museum. Places like Ironbridge Gorge in the UK or various mill sites in New England (like Lowell) give you a physical sense of the scale. The noise of a single power loom is deafening; imagine five hundred of them running at once in a room with no ear protection.

The Industrial Revolution wasn't a "period" we finished. It’s an ongoing process of trying to figure out how to be human in a world designed for machines. We got the weekend and the lightbulb, but we also got the 40-hour work week and the climate crisis. It was the ultimate trade-off. Luckly, we don't have to drink the Thames water anymore.