He was obsessed. Honestly, there is no other way to describe how Leonardo da Vinci felt about the sky. While his contemporaries were busy painting frescoes or arguing over papal politics, Leonardo was staring at bats. He spent years filling the pages of the Codex Atlanticus and the Codex on the Flight of Birds with messy, frantic sketches of wings. He wanted to solve the riddle of the air. The result was the Leonardo da Vinci ornithopter, a machine designed to fly by flapping its wings just like a living creature.

It didn't work. Not then, anyway.

But to call it a failure is to miss the entire point of how engineering actually evolves. Leonardo wasn't just a painter who liked gadgets; he was essentially the world's first biomechanic. He realized that if humans were going to leave the ground, we couldn't just wish ourselves upward. We needed to understand the physics of displacement and resistance. He looked at a bird’s wing and didn’t just see feathers; he saw a lever. He saw a system of pulleys and tendons.

The Bat-Wing Obsession and the Mechanics of Failure

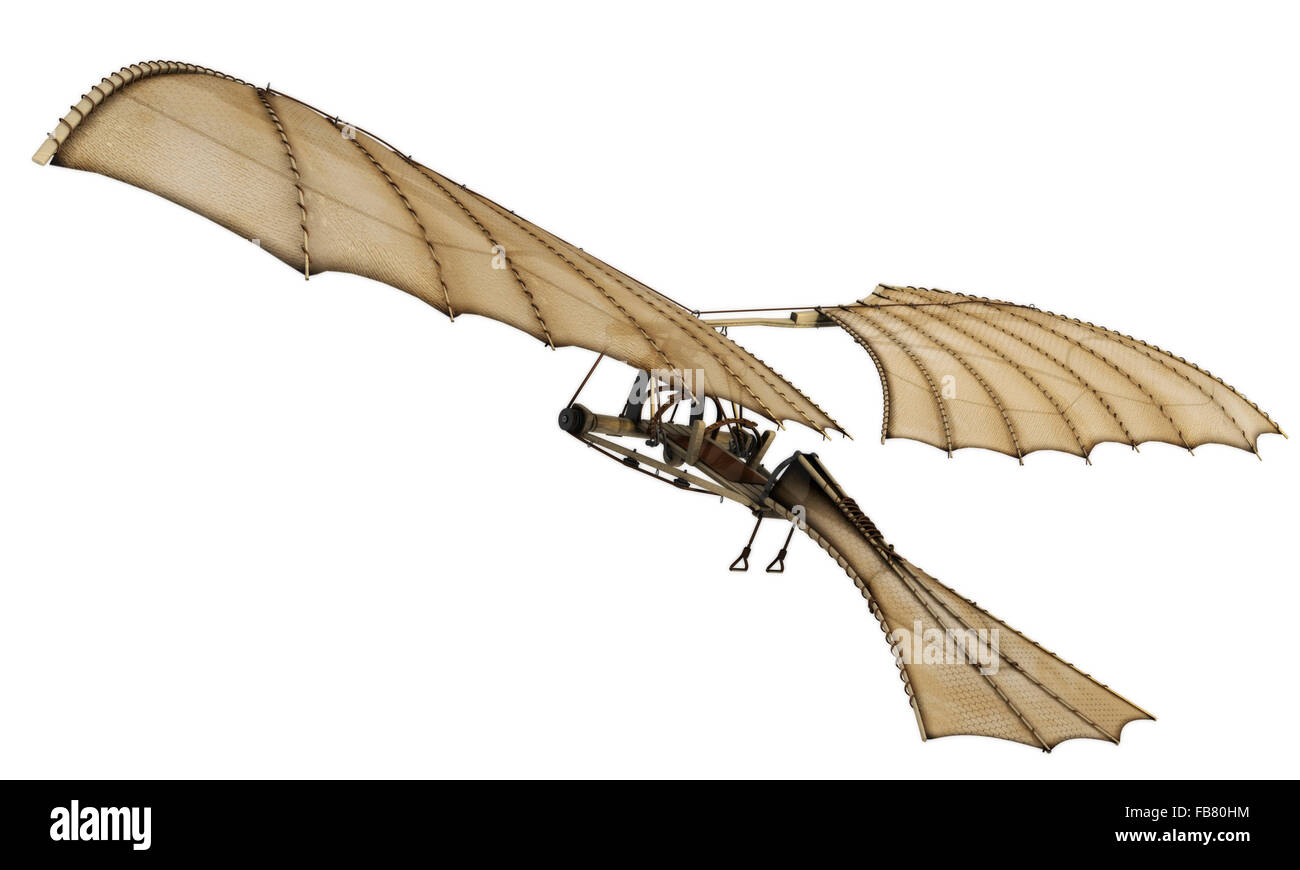

Leonardo’s most famous design for the Leonardo da Vinci ornithopter looks remarkably like a bat. He chose the bat as his muse because their wings are membranes. He figured that a skeleton covered in airtight silk would be more efficient than something made of feathers, which might let air leak through. The logic was sound for the 15th century.

The machine was massive. It featured a span of over 33 feet. The pilot was supposed to lie face down on a wooden plank, right in the center of the chaos. To get the thing to flap, the pilot had to use their entire body. We’re talking about a grueling system of stirrups for the feet and a windlass for the hands.

Imagine the physical toll. Leonardo’s notes show he was calculating how much force a human could actually generate. He eventually hit a wall. A depressing wall. Humans are simply too heavy and too weak. Our pectoral muscles are nothing compared to a bird’s. Even if he had built the machine out of the lightest pine and the finest silk available in Renaissance Milan, it wouldn't have generated the lift-to-weight ratio required for takeoff.

Why the Design Never Left the Ground

Gravity is a jerk. Leonardo understood this better than most, but he lacked a power source. In 1485, there were no internal combustion engines. There were no lithium-ion batteries. There was just muscle, bone, and sweat.

He experimented with different layouts. One version had the pilot standing upright. Another used a ladder-like system. He even thought about using a giant bowspring to store energy, sort of like a clockwork motor, to help with the flapping motion. But the math didn't add up. The Leonardo da Vinci ornithopter was destined to remain a dream on parchment because the materials of the era—wood, leather, and raw silk—were just too heavy for the limited power a human body can provide.

🔗 Read more: Is the 75 Class QLED 4K QE1D Actually Worth It? My Honest Take

Interestingly, Leonardo eventually realized this himself. If you look at his later sketches from around 1505, he starts moving away from active flapping. He begins drawing gliders. He noticed that big birds, like hawks and eagles, don't flap much when they’re high up. They catch thermals. This shift in his thinking shows a transition from "mimicking nature" to "understanding aerodynamics."

Breaking Down the Ornithopter's Anatomy

Most people think it’s just one drawing. It’s not. There are dozens of variations of the Leonardo da Vinci ornithopter scattered throughout his notebooks.

The "Flying Machine" (Macchina del Volo) usually consists of these core components:

- A central fuselage made of shaped wood.

- Retractable wings that used a "valve" system, where the wings would open on the upstroke to reduce resistance and close on the downstroke to push air.

- A complex series of joints made of leather and cords to mimic the carpometacarpus (the wrist bone) of a bird.

- A tail rudder, though this was often an afterthought in the early designs.

He even designed a retractable landing gear. Think about that. In the late 1400s, a guy was thinking about how to prevent a pilot's legs from breaking upon impact with the Italian countryside. He suggested using "ladders" that would act as shock absorbers.

The Materials He Had to Work With

He was limited by his time. He used:

- Fir and Pine: Light but prone to snapping under high torque.

- Raw Silk: Often coated with starch or wax to make it "airproof."

- Ox-hide: Used for the "tendons" and joints because it was tough and flexible.

If Leonardo had access to carbon fiber and high-torque electric motors, his designs probably would have worked. We know this because modern researchers at institutions like the University of Toronto have actually built functional ornithopters. In 2010, their human-powered "Snowbird" sustained flight for 19 seconds. It was a direct spiritual descendant of Leonardo’s sketches, just with better plastic.

The Legacy: From Renaissance Sketches to Modern Drones

Why do we still care? Because Leonardo’s work on the Leonardo da Vinci ornithopter laid the groundwork for the science of fluid dynamics. He was the first to describe the "impact" of air. He realized air is a fluid. He wrote about how air under a wing becomes more compressed than the air above it—a precursor to the principles later formalized by Daniel Bernoulli.

We see his influence in modern "flapping-wing" drones. These are often called Micro Air Vehicles (MAVs). Companies and military researchers use them because they are stealthy and more maneuverable in tight spaces than traditional quadcopters. They look like dragonflies or hummingbirds.

Modern Recreations and What They Taught Us

Engineers at the National Air and Space Museum and various tech labs have spent decades trying to build Leonardo’s exact specs. Most of the time, the wood snaps. The sheer force required to flap a 30-foot wing creates immense stress on the central crank.

But these failures taught us about structural integrity. Leonardo’s sketches of "fused" wood—laminating different types of wood to gain strength—were centuries ahead of their time. He was thinking about composites before we even had a word for them.

He also obsessed over the "screw." This led him to the Aerial Screw, which most people call the first helicopter. While distinct from the ornithopter, it was born from the same feverish need to conquer the air. He was attacking the problem from every angle: flapping, screwing, and gliding.

Common Misconceptions About the Flying Machine

A lot of people think Leonardo actually built one and crashed it. There’s a popular legend that his assistant, Tommaso Masini, tried to fly a version from Mount Ceceri and ended up with broken legs. There’s no hard evidence for this.

Most historians, including Martin Kemp, a leading Leonardo scholar, believe these machines remained "paper inventions." Leonardo was a perfectionist. He knew the weight was wrong. He kept refining the drawings because he was chasing a mathematical truth he couldn't quite reach with the tools in his workshop.

Another myth is that he "stole" the idea. While people have wanted to fly since Icarus, Leonardo was the first to apply actual anatomy to the problem. He dissected birds. He dissected human shoulders. He was looking for the mechanical bridge between the two. That’s not copying; that’s pioneering.

Actionable Insights: Learning from Leonardo’s Process

If you’re a designer, an engineer, or just someone who likes making things, the Leonardo da Vinci ornithopter offers a masterclass in "productive failure."

- Observe the source, then simplify: Leonardo didn't just draw a bird; he looked at the mechanics of the wing. If you’re solving a problem, look at how nature does it, but don't be afraid to swap feathers for silk if it makes more sense for your "machine."

- Acknowledge your constraints: Leonardo’s biggest hurdle was the lack of an engine. In your own projects, identify your "missing engine" early. Is it a lack of funding? A lack of technology? Knowing what you can't do is as important as knowing what you can.

- Iterate on paper first: The thousands of pages in his codices prove that ideas need to be beaten into shape. Don't rush to the "build" phase until you've explored the structural weaknesses on paper.

- Bridge the disciplines: The ornithopter wasn't just engineering; it was art and anatomy. The best solutions usually happen at the intersection of two fields that seemingly have nothing to do with each other.

To truly appreciate the Leonardo da Vinci ornithopter, you have to stop looking at it as a failed airplane. Look at it as a successful inquiry. It was a man asking the universe a very difficult question. The fact that we are now flying across oceans in metal tubes suggests that, eventually, the universe gave him an answer.

For those interested in seeing these designs in person, the Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci in Milan holds some of the most accurate physical reconstructions based on his original notes. Seeing the sheer scale of the wooden gears and the delicacy of the "wings" changes your perspective on how ambitious this Renaissance genius truly was.

Check out the Codex Atlanticus online through various museum digital archives to see the raw, unedited sketches. You can see where his pen skipped, where he crossed out ideas, and where he began to realize that the secret to flight wasn't in the flapping, but in the wind itself.