He was a messy eater. He left dozens of projects unfinished. He spent years obsessing over why the sky is blue and how wood-peckers’ tongues actually work. Most people think of the "Mona Lisa" when they hear his name, but honestly, the real magic—the raw, unfiltered brain power—is found in the thousands of pages of leonardo da vinci drawings scattered across various notebooks known as codices. These aren't just sketches. They are a high-speed data dump of a mind that couldn't stop questioning reality.

It's kinda wild to think about.

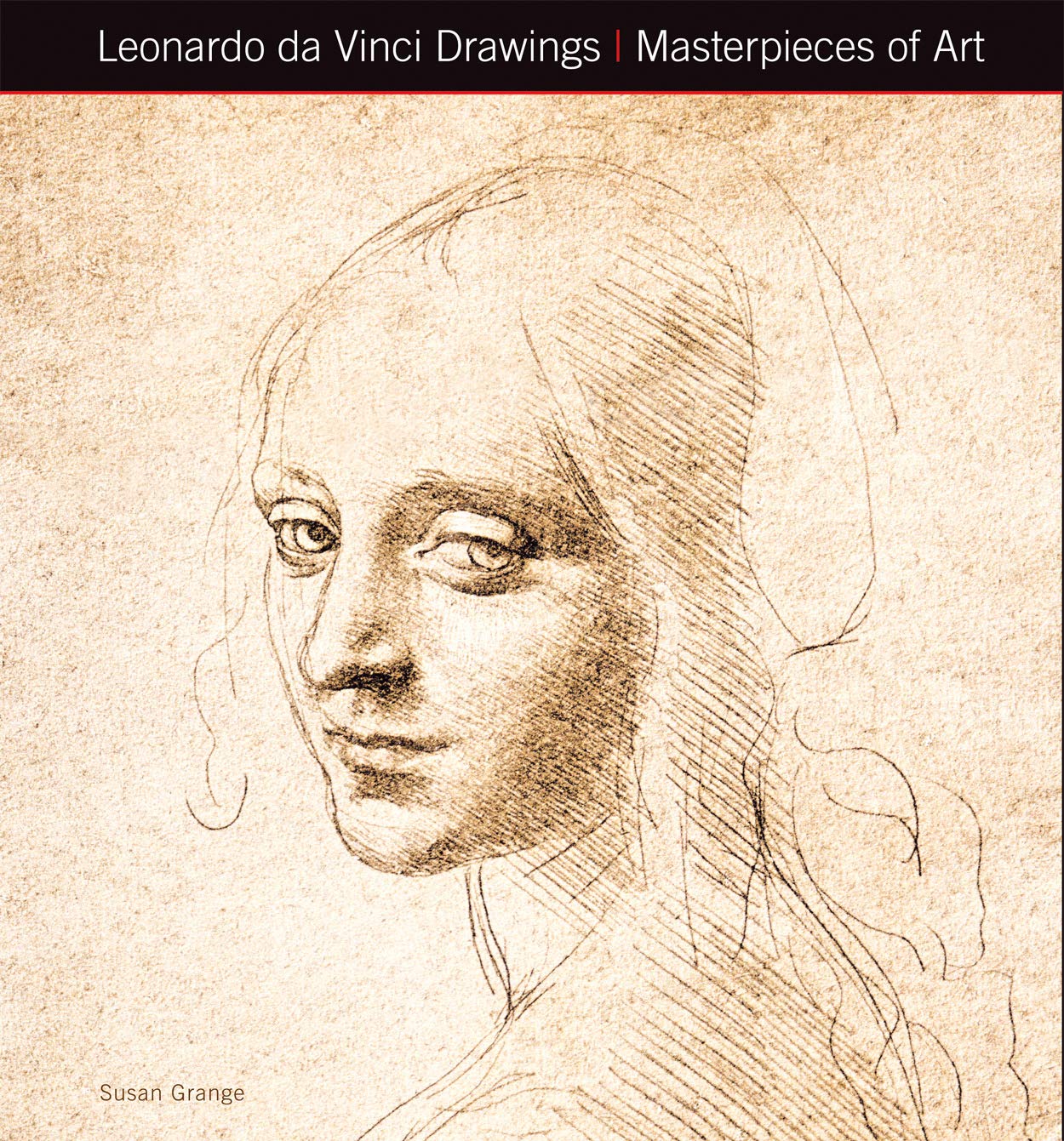

Leonardo didn't have a formal education in the way we do now. He was "omo sanza lettere," an unlettered man. Because he didn't read Latin well, he used his eyes. He drew to understand. When you look at his silverpoint studies of drapery or those frantic red chalk sketches of horses, you’re not just looking at art. You’re looking at a man trying to reverse-engineer the universe on a piece of paper.

The Anatomy of Obsession

Leonardo didn't just draw muscles; he hunted for the source of life. Most artists of the Renaissance stayed on the surface. They wanted the "heroic" look. Leonardo? He went deeper. He actually performed dissections—roughly 30 of them—at hospitals in Florence, Milan, and Rome.

His anatomical leonardo da vinci drawings changed everything. Look at his "Great Lady" drawing or his studies of the human heart. He was the first to realize the heart had four chambers, not two. He even built a glass model of an aortic valve and pumped water with grass seeds through it to see how the blood swirled. That’s not art. That’s fluid dynamics.

He had this weird, beautiful habit of mixing things up. In the middle of a page detailing the nerves of the shoulder, he might doodle a flower or a geometric puzzle. It shows a mind that didn't see "subjects." To him, the way a river flows around a rock was fundamentally the same as how blood flows through a valve. It's all just motion. He called it moto.

The famous "Vitruvian Man" is the big one everyone knows. It’s basically a meme at this point. But it’s actually a solve for an ancient architectural puzzle by Vitruvius. Leonardo wanted to prove that the human body could fit perfectly inside both a square and a circle. It’s a statement of faith in the "man as a microcosm" idea. We are the world in miniature.

Why the Notebooks Are So Weird

If you’ve ever tried to read a leonardo da vinci drawing and felt like you were having a stroke, join the club. He wrote in mirror script. Right to left.

People love to say he was hiding his secrets from the Church or rivals. That's probably nonsense. Honestly, he was left-handed. Writing right-to-left meant he didn't smudge the ink as he moved across the page. It was a practical hack.

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

These notebooks—the Codex Atlanticus, the Codex Leicester (which Bill Gates famously bought for $30.8 million), and the Codex Arundel—are chaotic. They aren't organized. He would pick up a notebook he hadn't touched in ten years and start writing in the margins of a page about bridge building to talk about the flight of birds.

The Weapons of War

Leonardo hated war. He called it pazzia bestialissima—the most beastly madness.

And yet, he spent a huge chunk of his life drawing terrifying machines. He drew scythed chariots designed to limb people, giant crossbows, and a tank that looked like a wooden turtle. You can find these leonardo da vinci drawings primarily in the Codex Atlanticus.

There’s a bit of a debate among historians here. Some, like Martin Kemp, suggest Leonardo might have intentionally designed these machines with flaws—like the tank’s gears being set in opposite directions so it couldn't move—because he didn't actually want them built. Others think he was just a bit of a dreamer who didn't always care about the "engineering" reality as much as the concept. He was a consultant. He needed to impress dukes like Ludovico Sforza to keep his studio running.

The Science of Water and Wind

Leonardo was obsessed with spirals. You see them in the hair of his portraits, in his drawings of storms, and in his studies of "deluge."

Water was "the driving force of all nature" to him. He spent decades trying to map the turbulence of the Arno River. His drawings of water are so accurate that modern hydrologists use them to study vortex behavior. He’d spend hours sitting by a stream, throwing things in, watching the eddies, and then sketching them with a speed that shouldn't have been possible before photography.

Then there are the birds.

He didn't just want to fly; he wanted to understand the mechanics of lift. He watched how birds used their wings to balance against the wind. His drawings of flying machines—the ornithopters—are beautiful, but they were doomed. He eventually realized human muscles weren't strong enough to power them. So, he pivoted. He started drawing gliders. He realized that the air acts like a fluid. If you understand the air, you can ride it.

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

The Materials He Used

You can’t talk about leonardo da vinci drawings without talking about the "how."

He didn't have a local art store. He had to make his stuff.

- Silverpoint: This was his "hard mode." You use a silver stylus on specially prepared paper. You can’t erase it. Every line is permanent. This is where he developed that insane precision.

- Red and Black Chalk: He loved these for his "sfumato" effect. He’d smudge the chalk to create those soft, smoky transitions that make his faces look like they’re breathing.

- Pen and Ink: Usually iron gall ink. It eats into the paper over time, which is why some of his drawings have a brownish tint today.

Modern Misconceptions

People think he was a lonely genius working in a vacuum. He wasn't.

He was part of a vibrant court culture. He had students like Salai and Boltraffio who copied his work. Sometimes, when you see a "Leonardo" drawing, it's actually a student's copy that he touched up. Sorting those out is the career work of people like Carmen Bambach at the Met. It’s detective work involving paper watermarks and left-handed vs. right-handed hatching lines.

Another big myth: that he "invented" the helicopter. He drew an aerial screw. It’s a cool drawing. But it wouldn't have flown. It was a conceptual leap, not a blueprint. He was thinking about the idea of a screw moving through air like a screw moves through wood.

How to Actually See Them

Most of these drawings are tucked away in royal collections or climate-controlled vaults. They are light-sensitive. If you leave them out, they fade into nothing.

However, technology has made them more accessible than ever. The British Royal Collection Trust has digitized hundreds of them in high resolution. You can zoom in until you see the texture of the paper. It’s better than seeing them in person behind three inches of bulletproof glass.

Why They Matter to You Now

Why should you care about 500-year-old sketches?

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Because Leonardo’s drawings are a masterclass in observation. We live in a world of "glance and scroll." Leonardo lived in a world of "stare and wonder." He’d spend three days looking at how a goat’s eye reflects light.

By studying his work, you realize that the divide between "art" and "science" is a modern invention. To Leonardo, they were the same thing. Curiosity has no boundaries.

Actionable Ways to Study Leonardo's Techniques

If you want to understand his process, don't just read about it. Try to do it.

Start an Observation Journal

Don't draw "well." Draw to see. Pick an object—a leaf, a glass of water, your own hand. Try to map every wrinkle and shadow. Leonardo used "hatching" (parallel lines) to create depth. For a right-handed person, these usually tilt from top-right to bottom-left. Leonardo, being a lefty, went from top-left to bottom-right.

Practice Sfumato with Charcoal

Get some willow charcoal. Draw a face and then use your finger or a blending stump to blur the edges. Leonardo believed there are no hard lines in nature. Everything is a transition of light and shadow.

Look for the "Why"

When you draw something, ask why it looks that way. If you’re drawing a tree, don't just draw "leaves." Draw the way the branch reaches for the sun. Leonardo’s leonardo da vinci drawings are explanations, not just pictures.

Visit Digital Archives

Stop looking at low-res Pinterest crops. Go to the source.

- The Royal Collection Trust (UK)

- The Codex Atlanticus (Ambrosiana Library, Milan)

- The Louvre's online database

When you look at a Leonardo drawing, you're looking at a man who refused to be bored. He proved that if you look at anything—even a puddle of water—long enough, it becomes the most interesting thing in the world.

To truly appreciate leonardo da vinci drawings, you have to stop looking for the "art" and start looking for the "question." Every line he drew was an answer to something he had asked himself that morning. That curiosity is his real legacy. It's more than paint on a canvas; it's the blueprint of a human mind that never grew up and never stopped asking "why?"

If you want to go deeper, look into the specific history of the Codex Leicester. It’s one of the few notebooks where Leonardo focuses almost entirely on one subject—water—and it provides the clearest look at how his scientific method functioned decades before the "Scientific Revolution" even had a name. It’s proof that Leonardo wasn't just ahead of his time; he was living in a future he had to invent for himself.