Most people think of Lee Miller as a muse. You've probably seen the Man Ray portraits or heard about her modeling for Vogue in the twenties. She was beautiful. It's an easy narrative to swallow—the "pretty girl" who sat for the great male surrealists. But if you actually look at the photographs by Lee Miller, you realize she wasn't just some passive subject. She was dangerous with a camera. Honestly, her work is some of the most unsettling, visceral, and technically brilliant stuff to come out of the 20th century. She didn't just take pictures; she documented the collapse of civilization while maintaining a surrealist's eye for the bizarre.

Miller’s career didn't follow a straight line. There was no "five-year plan." She went from being a high-fashion model to a fine-art photographer in Paris, then a socialite in Cairo, and finally a combat correspondent in the middle of World War II. It’s a lot. If you try to pin her down to one style, you'll fail. Her work is a messy, beautiful, and often horrifying collection of what happens when a surrealist mind meets the reality of a world at war.

The Surrealist Roots: More Than Just Man Ray

In 1929, Miller tracked down Man Ray in Paris and told him she was his new student. He said he didn't take students. She told him he did now. That's Lee. Together, they "discovered" solarization—that weird, halo-like effect where the tones of a photo are partially reversed. For a long time, Man Ray got all the credit. But Miller was the one who actually stumbled onto it in the darkroom when something crawled across her foot and she turned on the light by accident.

Her early photographs by Lee Miller from this era are strange. She had this knack for making the ordinary look alien. Think about her shot of severed breasts on a dinner plate. It’s titled Untitled (Severed Breast from Radical Mastectomy), circa 1930. It's gruesome, sure, but it's framed with the clinical detachment of a fashion shoot. She was poking fun at the male gaze long before that was a buzzword. She took the body apart. She looked at a neck or a torso and saw a landscape. It wasn’t about "beauty" in the way Vogue wanted it; it was about the uncanny.

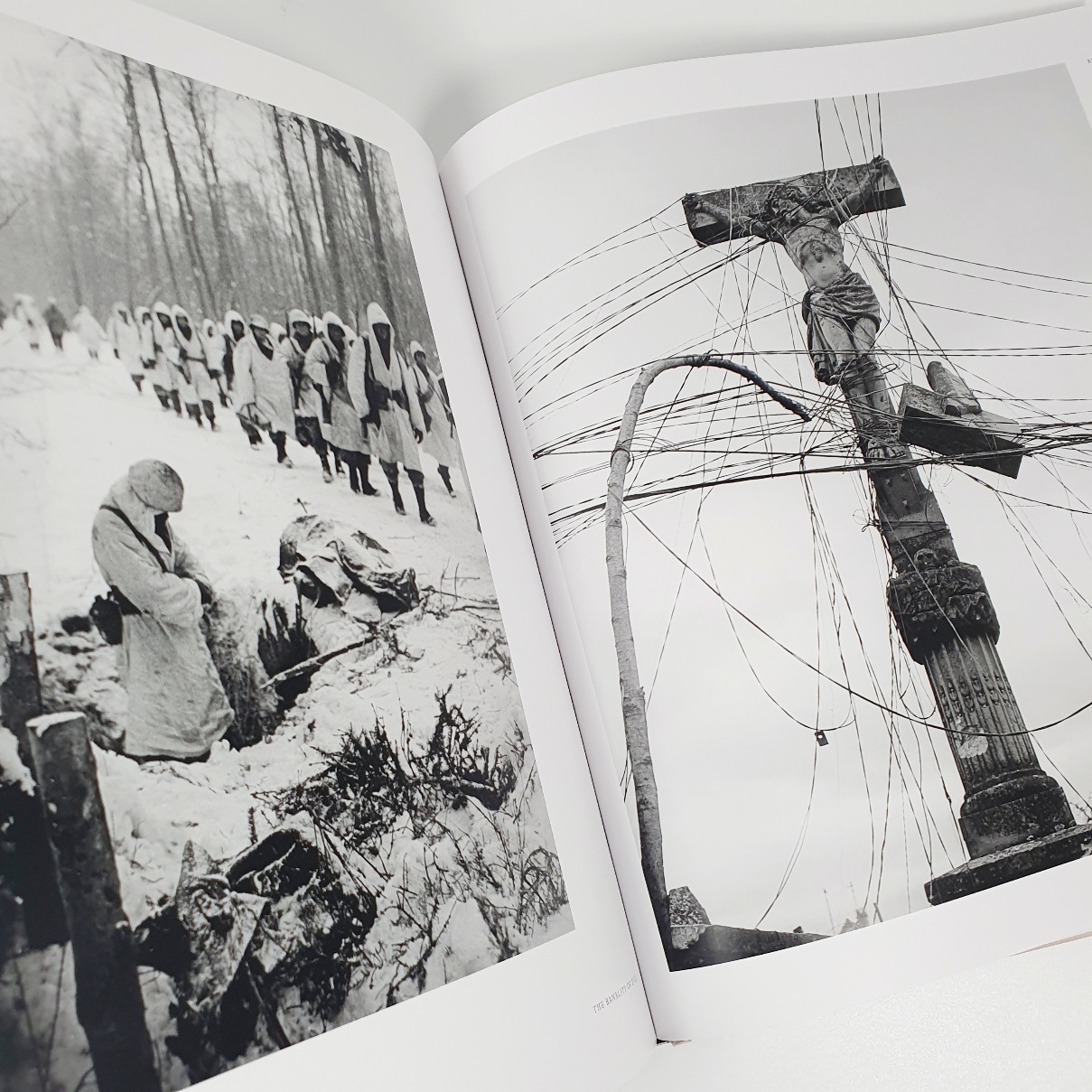

She lived in a world where Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst were just guys she hung out with. But while they were painting melting clocks, Miller was finding surrealism in the real world. She found it in the way shadows fell across a desert in Egypt or the way a torn net looked like a spiderweb. She had this "found" surrealism that felt way more grounded than the stuff happening on canvases in Paris.

From Fashion to the Frontlines

When the war broke out, Miller was in London. She could have left. She was an American citizen with plenty of money and connections. She stayed. She started shooting for Vogue, but the pictures changed. Instead of just dresses, she was shooting women in fire masks during the Blitz. These photographs by Lee Miller captured a weirdly feminine side of the war—nurses, pilots, and ordinary women trying to keep some semblance of life together while bombs dropped on their heads.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

But she got bored. She wanted to be where the action was.

In 1942, she became an official U.S. Army combat correspondent. Think about that for a second. A former fashion model, now in a uniform, trekking through the mud of France and Germany with a Rolleiflex camera around her neck. She was one of the few women allowed to do it. And she didn't play it safe. She followed the troops through the liberation of Paris and eventually into the heart of the Third Reich.

The Horror of the Camps

This is where the conversation about Miller usually gets heavy. It has to. You can't talk about photographs by Lee Miller without talking about Buchenwald and Dachau. She arrived at the camps just hours after they were liberated. While other photographers were focused on the sheer scale of the tragedy, Miller’s surrealist training kicked in in the worst way possible. She saw the "beautiful" horror.

She photographed a pile of bone ash. She photographed the "Dead SS Guard in Canal," where the water creates this shimmering, almost peaceful ripples around a bloated corpse. It’s haunting because it’s composed so well. It’s almost too pretty for what it is. That was her power. She forced you to look at things you wanted to turn away from by making them impossible to ignore.

"I implore you to believe this is true," she wrote to her editor at Vogue, Audrey Withers. She knew people wouldn't believe the photos. She knew the world would try to look away.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

Then, of course, there’s the bathtub photo. You’ve seen it. Miller is sitting in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub in his Munich apartment. It was taken by David E. Scherman, but it’s 100% her vision. Her dirty combat boots are on the bathmat, getting mud from Dachau all over the Fuhrer’s floor. A portrait of Hitler sits on the edge of the tub. She’s scrubbing herself clean of the filth of the camps in the most private space of the man who built them. It’s the ultimate "f*** you" in art history. It’s a performance piece captured in a single frame.

The Aftermath: Silence and Discovery

After the war, Lee Miller basically stopped. She moved to Farley Farm House in Sussex, married Roland Penrose, and became a gourmet cook. She buried her past. Literally. She threw her negatives and journals into boxes in the attic and didn't talk about the war. Her own son, Antony Penrose, didn't even know she had been a world-class photographer until after she died in 1977.

He found thousands of negatives tucked away.

It’s kind of heartbreaking. She had massive PTSD before people knew what to call it. She drank. She struggled. But the legacy she left behind in those boxes changed how we view 20th-century photography. She wasn't just a "female photographer." She was a witness.

Why We Still Care About Her Work

So, what's the big deal? Why are we still looking at photographs by Lee Miller in 2026?

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

Mainly because she broke the rules of how women were "supposed" to see the world. She didn't look for softness. She looked for truth, even when it was ugly. Her work bridges the gap between the dream world of surrealism and the brutal reality of the 1940s. She showed us that those two worlds aren't actually that far apart.

If you’re looking to understand her impact, don't just look at the famous shots. Look at her street photography in London during the war. Look at the way she captured the displaced people in Europe after the fighting stopped. There’s a humanity there that’s often missing from more "professional" photojournalism. She cared about the people in the frame, even if she was framing them like a piece of art.

How to Appreciate Miller’s Work Today

If you want to dive deeper into her portfolio, you’ve got to do more than a quick Google search. Her work is best experienced in context.

- Visit Farley Farm House: If you’re ever in East Sussex, go to the Lee Miller Archives. Seeing where she lived—and where she hid her work—gives you a much better sense of the woman behind the lens.

- Compare her "Vogue" work with her war work: Look at the lighting. You’ll notice that she used the same dramatic, high-contrast style for a fashion model as she did for a tank commander. It’s a weirdly consistent aesthetic.

- Study the composition: Miller loved diagonals. She loved frames within frames. She used the physical environment to trap her subjects or set them free.

- Read her writing: She was a brilliant writer. Her captions and articles for Vogue are just as sharp and unsentimental as her photos.

Lee Miller was a complicated person. She wasn't a saint, and she wasn't just a victim of her time. She was a powerhouse who took the camera—a tool mostly controlled by men—and used it to document the world on her own terms. Her photos aren't always easy to look at, but that's exactly why they're important. They demand your attention. They refuse to let you be comfortable.

To truly understand Miller, start by looking at her "Portrait of Space" (1937). It's a shot of the Egyptian desert through a torn mosquito net. It captures everything she was about: the vastness of the world, the beauty of decay, and the fact that there’s always something—a veil, a net, a lens—between us and the truth.

Actionable Insights for Photography Enthusiasts

If you're inspired by Miller’s approach to the craft, here’s how to apply her "Surrealist Eye" to your own work:

- Look for the Uncanny in the Ordinary: Miller didn't need a studio. She found surrealism in cracked sidewalks and shadow patterns. Try shooting everyday objects from extreme angles or in "wrong" lighting to see how their meaning changes.

- Don't Shield the Viewer: If you're documenting something difficult, don't try to make it "nice." Miller’s power came from her refusal to soften the blow. Be honest with your subject matter.

- Master Lighting and Contrast: Use hard shadows to create mystery. Miller’s use of solarization and high-contrast black and white proved that what you don't see is often as important as what you do.

- Context is Everything: A photo of a bathtub is just a bathtub—unless you know who owned it. When building a series, consider the narrative weight of the locations and objects you choose to frame.

The best way to honor Lee Miller’s legacy is to keep looking at the world with a critical, slightly cynical, and deeply curious eye. Her work reminds us that the line between "art" and "witness" is much thinner than we think.