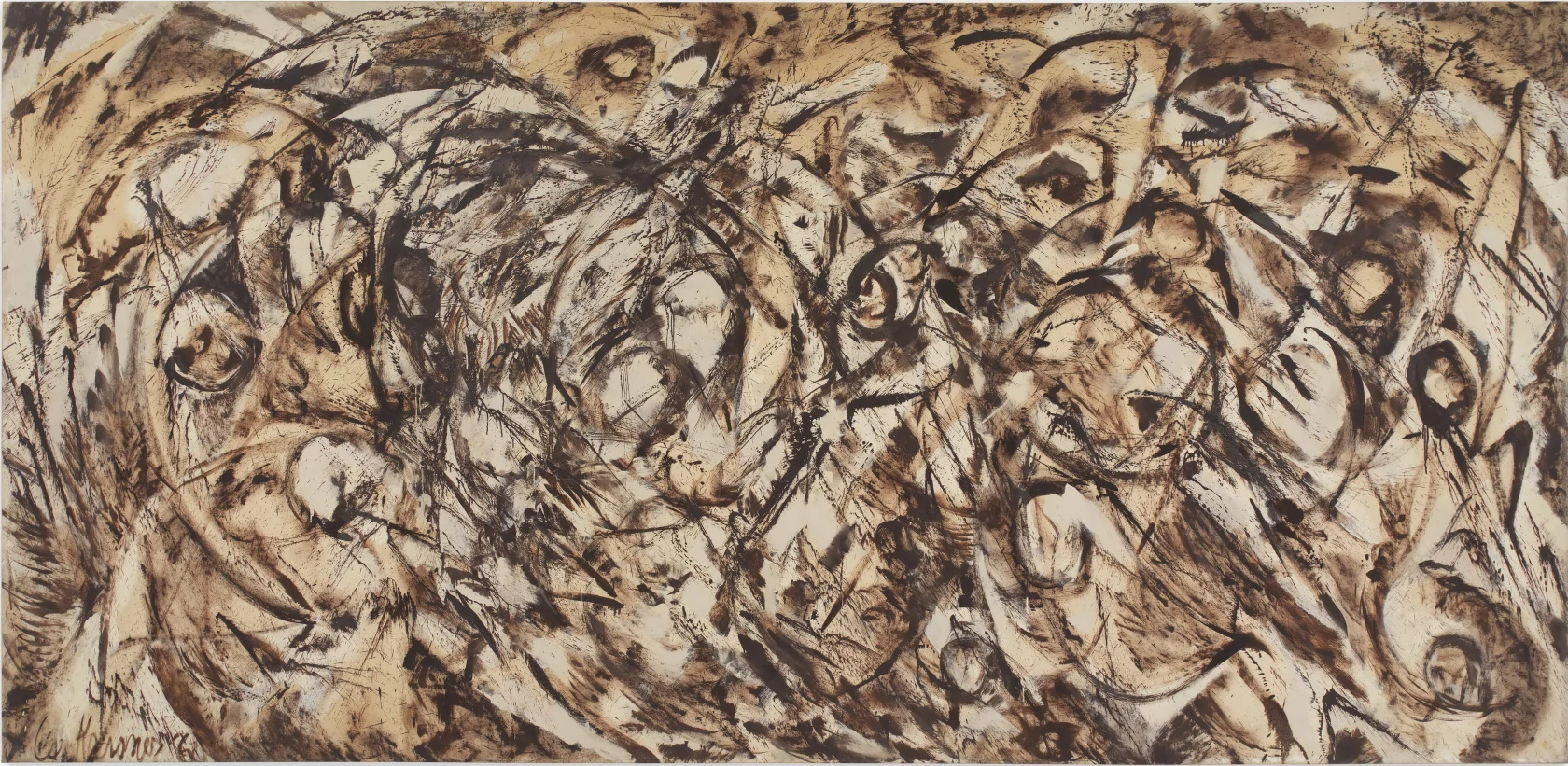

Honestly, if you ever find yourself standing in front of Lee Krasner The Seasons, you’re going to feel small. Not just because it’s massive—though at 17 feet wide, it’s basically a wall of paint—but because of the sheer noise it makes. It’s loud. It’s a 1957 masterpiece that shouldn’t really exist, considering the wreck Krasner’s life was when she painted it.

Most people look at Abstract Expressionism and see splashes. They see Pollock. They see a bunch of "angry men" throwing ego at a canvas. But Krasner? She was different. She was a "tough cookie," as some described her, who spent years working in a tiny bedroom while her husband, Jackson Pollock, took over the big barn studio. Then he died in a car crash in 1956. A year later, she moved into that barn. She took over the space. And out came The Seasons.

Breaking the Silence of the Barn

It’s kinda wild to think about the logistics. For a decade, Krasner kept her work small. Her "Little Images" series was tiny, mostly because she didn't have room to breathe. When she finally stepped into Pollock’s old studio, the scale of her ambition just exploded.

The Seasons isn't just a big painting. It’s a statement of survival. While everyone expected her to paint something dark or mournful after losing Jackson, she did the opposite. She went lush. She went green. She went for these explosive, bulbous shapes that look like they’re screaming "I'm still here."

The canvas measures a staggering $92 \ 3/4 \times 203 \ 7/8$ inches. That is nearly eight feet tall and seventeen feet wide. You can't just "look" at it; you have to walk past it. It’s an experience.

Why the Colors Feel So Weird

Usually, when we think of "autumn" or "winter," we think of death or dormancy. Krasner didn't play by those rules. In Lee Krasner The Seasons, the palette is dominated by:

- Earth greens that feel heavy and wet.

- Flesh-toned pinks that look remarkably like human curves.

- Deep blacks that provide the "inner rhythm" she was obsessed with.

She used oil and house paint. She didn't just brush it on; she lived in it. There’s a certain violence to the brushstrokes, yet it’s organized. It’s what she called her "breaks"—these moments where her style would just shatter and reinvent itself. She wasn't interested in a "signature look" like Rothko’s rectangles or Pollock’s drips. She wanted to evolve.

The "Umber" Problem and the Earth Green Series

A lot of people get The Seasons mixed up with her later "Night Journeys" or the "Umber" series. Those were the paintings she did when she couldn't sleep. She was a chronic insomniac after Pollock died, and since she couldn't see color well under artificial light, she just used white, black, and brown.

But The Seasons belongs to the Earth Green series. It’s the bridge. It’s the moment she decided that being "Jackson Pollock's widow" wasn't her only identity. Critics at the time? They weren't always kind. Some found the organic, almost anatomical shapes a bit too much. But if you look at it today at the Whitney Museum of American Art, it feels incredibly modern. It feels like nature is trying to reclaim the room.

It’s Not Just "Pretty" Nature

Krasner’s version of nature is sort of terrifying. It’s not a garden; it’s a jungle. The shapes in The Seasons are often described as "vegetal," but they also look like body parts. Breasts, bellies, seeds, roots—it’s all tangled together.

She was heavily influenced by Henri Matisse and his use of color, but she traded his calm for a more rhythmic, chaotic energy. She once said, "I like a canvas to breathe and be alive." Standing in front of this thing, you can practically hear it panting.

📖 Related: Kanye West Famous Music Video: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Why Most People Get Krasner Wrong

The biggest misconception is that she was just a "student" of the greats. Sure, she studied under Hans Hofmann. Yeah, she was married to the most famous painter in America. But Krasner was often the one teaching them.

She was a ruthless editor. She’d take her own paintings, hate them, rip them into shreds, and then glue them back together to make collages. The Seasons represents a rare moment where she let the canvas stay whole and huge. She wasn't hiding anymore.

Getting the Most Out of Lee Krasner The Seasons

If you’re lucky enough to see it in person, don't just stand in the middle. Try these three things:

- Walk the perimeter. Start at the left and walk slowly to the right. Notice how the rhythm changes. It’s like a musical score.

- Look for the "ghosts." Krasner often painted over things. You can see the layers, the history of her mistakes and corrections.

- Check the edges. See how the paint almost wraps around? She wanted the viewer to feel "immersed," not just like they were looking at a window.

Final Takeaway for Your Next Museum Trip

Next time someone brings up the "Abstract Expressionists," remind them that the biggest, most energetic canvas in the room might just belong to the woman who was told her work was "so good you wouldn't know it was done by a woman." (Yes, Hofmann actually said that to her. Gross.)

Lee Krasner The Seasons is more than just a painting of the weather. It’s a map of a woman coming back to life. It’s proof that you can take the space you were denied and fill it with something beautiful, messy, and loud.

To truly understand Krasner's impact, your next step should be to look at her "Little Images" series from the late 1940s. Comparing those tiny, cramped "hieroglyphic" paintings to the massive scale of The Seasons is the only way to see how far she actually traveled artistically. You'll see exactly how she broke out of the bedroom and into the barn.