Walt Whitman was kind of a mess, honestly. He spent his whole life rewriting the same book, losing jobs, and ticking off the 19th-century literal police because he didn't use rhymes. But here we are. Over 150 years later, and quotes from Leaves of Grass are still the go-to for anyone trying to feel something deeper than a double-tap on a screen.

Whitman didn't write for the elite. He wrote for the guy driving the stagecoach and the woman working in the factory. He was obsessed with the idea that you, personally, are a miracle. It’s not just poetry; it’s a vibe. It’s a loud, messy, sweaty celebration of being alive.

The Weird Power of Whitman's Most Famous Lines

Most people know the "O Captain! My Captain!" bit because of Dead Poets Society. It’s iconic. But if you actually dig into the text, the real meat is in the stuff that feels a little more dangerous.

Take this line: "I celebrate myself, and sing myself, / And what I assume you shall assume."

That sounds incredibly cocky at first. Like, okay Walt, calm down. But he’s not being a narcissist. He’s saying that he is made of the same atoms as you. He’s saying that if he’s great, you’re great too. It’s radical equality. In a world where we’re constantly told we aren't enough—not rich enough, not fit enough, not productive enough—Whitman is over here shouting that just existing is a win.

He didn't care about being polished. He wanted to be "barbaric."

"I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world."

Think about that. A "yawp." It’s not a speech. It’s not a tweet. It’s a raw, unhinged noise of existence. We spend so much time being curated. Whitman wanted us to be loud.

Why "Song of Myself" is Basically a Life Coaching Session

If you read "Song of Myself," you’ll notice it’s long. Really long. Whitman keeps adding to it in every new edition of the book. He couldn't stop.

One of the most requested quotes from Leaves of Grass comes from Section 51: "Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself, / (I am large, I contain multitudes.)"

This is arguably the most liberating sentence in American literature. We all feel like hypocrites sometimes. You want to be healthy but you eat the cake. You want to be kind but you get road rage. Whitman says: "So what?" Humans are complex. We aren't brands. We don't have to be consistent to be valid. You are allowed to change your mind. You are allowed to be a walking contradiction.

The Grass is Actually a Metaphor for Death (Sorta)

Whitman had this thing with grass. He called it the "beautiful uncut hair of graves."

That sounds a little goth, right? But he was actually being an optimist. He looked at a field of grass and saw a cycle. Nothing truly dies; it just turns into something else. To him, death wasn't a scary end-of-the-road thing. It was just a transition back into the earth.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

He wrote, "Has any one supposed it lucky to be born? I hasten to inform him or her it is just as lucky to die, and I know it."

That’s a heavy lift. Most of us spend our lives terrified of the end. Whitman looked at a blade of grass and found peace with it. He viewed the universe as a giant recycling program where energy never actually leaves the building.

Dealing With the Critics and the "Banned" Status

You have to remember that when the first edition of Leaves of Grass dropped in 1855, people were genuinely offended. The Boston Post basically said it was a pile of trash. They called it "gross" and "obscene."

Why? Because Whitman wrote about bodies. He wrote about "the scent of these arm-pits" being "finer than prayer."

He didn't separate the soul from the body. To him, your skin and your bones were just as holy as a church. This was scandalous in a Victorian era where people were literally putting "skirts" on piano legs to be modest. Whitman was out here writing about the physical joy of touch and the beauty of the human form without any shame.

The Civil War Changed Everything

Whitman wasn't just sitting in a room thinking deep thoughts. When the Civil War broke out, his brother George was wounded. Walt went to find him and ended up staying in Washington D.C. for years, working as a volunteer nurse.

He saw the worst of it. The amputations. The infection. The young boys dying alone.

This shifted his poetry. The quotes from Leaves of Grass that come from the Drum-Taps section are much more somber. They aren't just "yawping" anymore; they are grieving. He wrote "The Wound-Dresser," which is one of the most heartbreaking poems ever written about the cost of war. He stayed by the bedsides of soldiers, writing letters home for them, holding their hands.

It grounded his philosophy. It made his "celebration of life" feel earned, because he had seen so much death.

The Connection to Nature and the "Great Outdoors"

Whitman was basically the original "outdoor influencer," but without the filtered photos. He believed that if you spent enough time outside, you would eventually become a better person.

"Now I see the secret of the making of the best persons, / It is to grow in the open air and to eat and sleep with the earth."

There is some actual science to back this up now—forest bathing, vitamin D, all that—but Whitman knew it instinctively. He thought that cities made people cramped and judgmental. The "open road" was where you found your soul.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

When you look for quotes from Leaves of Grass, you’ll often find lines from "Song of the Open Road." It’s all about the journey.

- "Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,"

- "Healthy, free, the world before me,"

- "The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose."

He wasn't looking for a destination. He was looking for the freedom to just go.

How to Actually Use Whitman's Wisdom Today

It’s easy to read these lines and think, "Cool, that sounds nice," and then go back to scrolling. But Whitman intended for his work to be a manual for living.

If you want to live like a Whitmanite, you have to do three things.

First, stop being so hard on yourself for being complicated. Embrace the "multitudes." If you feel like a different person at work than you do at home, that's fine.

Second, get off the couch. Whitman didn't find his inspiration in a library; he found it walking the streets of Brooklyn and the woods of Long Island.

Third, look at people—really look at them. Whitman believed every single person he passed on the street was a "divine" being. Even the people you disagree with. Even the people who annoy you.

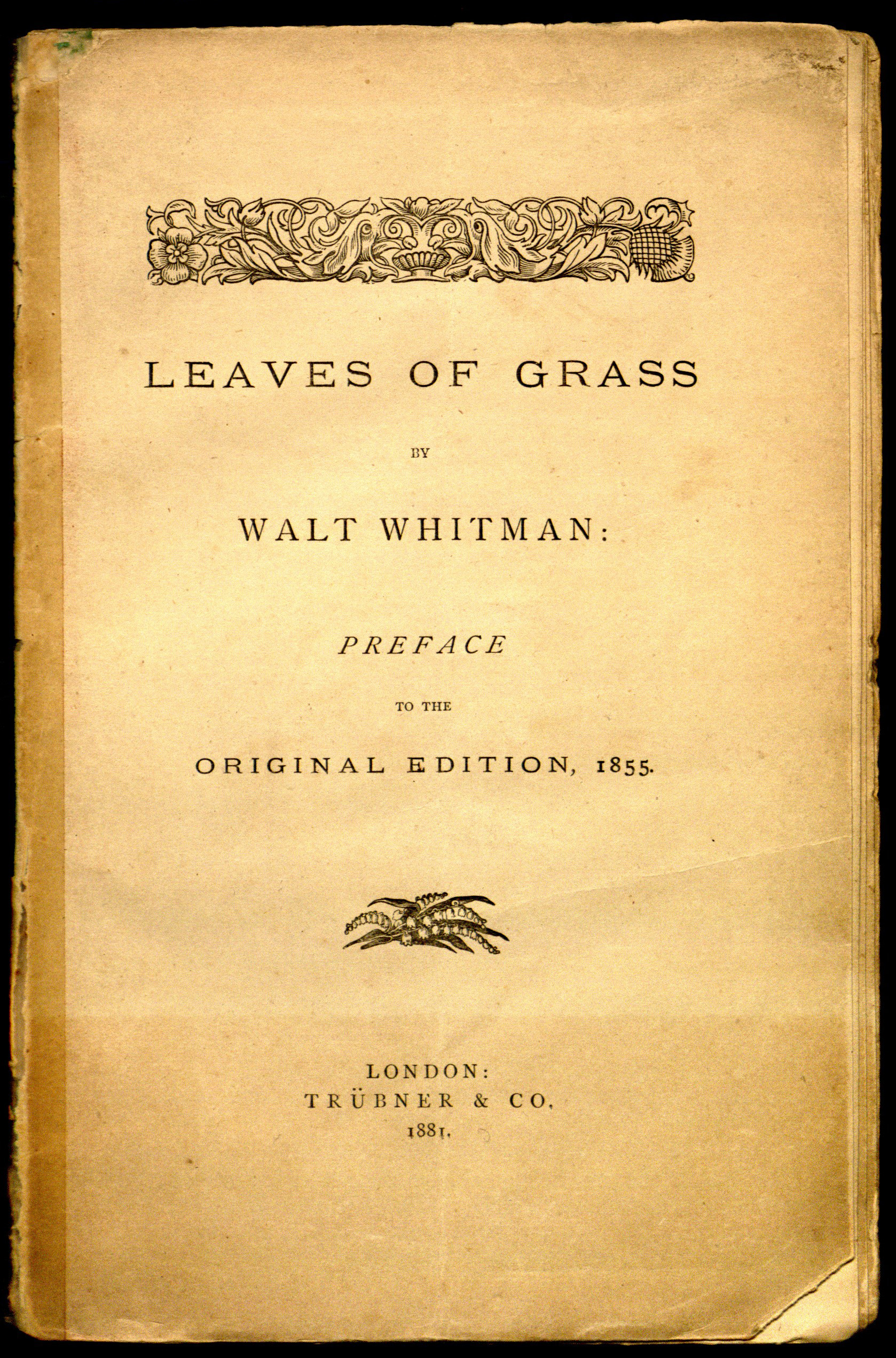

A Note on the Different Editions

If you're going to buy the book, be careful. There are like nine different versions.

The 1855 version is the "original gangster" edition. It’s raw, weird, and short. It has the original punch.

The "Deathbed Edition" (1892) is the one Whitman finished right before he died. It’s huge. It has everything. If you want the full experience of his life's work, that's the one to grab. Just be prepared to spend a few months in there.

Misconceptions People Have About Whitman

A lot of people think Whitman was some kind of hermit or a lonely guy. He wasn't. He was incredibly social. He loved the opera. He loved taking the ferry across the East River just to watch the crowds.

He was also deeply political. He believed that poetry could save the United States. He saw the country falling apart during the lead-up to the Civil War and thought that if Americans could just see the "divine" in each other, they wouldn't kill each other. He was wrong, obviously—the war happened anyway—but he never stopped trying to use words as a bridge.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

Another misconception: that his work is "hard" to read.

Honestly, it’s some of the easiest 19th-century stuff to digest. He doesn't use fancy metaphors that require a PhD. He uses words like "grass," "sun," "air," and "body." He talks to you like a friend.

Practical Steps for Reading Leaves of Grass

Don't try to read it cover to cover like a novel. You’ll get bored.

- Start with "Song of Myself." Just read Section 1 and Section 52.

- Read it out loud. Whitman wrote for the ear. The rhythm doesn't click until you hear the words vibrating in your throat.

- Take it outside. Go to a park. Sit under a tree. Read a few pages, then look at the people walking by.

- Mark it up. Highlight the lines that make you feel something.

Whitman said, "Camerado, this is no book, / Who touches this touches a man."

He wasn't kidding. He poured his entire physical and spiritual self into these pages. When you read quotes from Leaves of Grass, you aren't just reading old poetry; you’re making contact with a guy who lived through the most chaotic time in American history and still managed to love the world.

That’s a skill we all need right now.

Finding Your Own "Barbaric Yawp"

The ultimate takeaway from Whitman isn't just a list of pretty lines for a greeting card. It’s a challenge. He’s asking you what you’re going to do with your life.

He famously asked: "The powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse."

What’s your verse? It doesn't have to be a poem. It could be how you raise your kids, how you treat your neighbors, or how you build something new. The point is that you’re here, the "play" is happening, and you have a part to play.

Stop waiting for permission to be yourself. Whitman never did. He self-published his book because no one else would. He took the heat, he took the insults, and he kept writing until the day he died.

Go find a copy of the 1855 edition. Flip to a random page. Read until a sentence stops you in your tracks. Then, put the book down and go live your life. That’s exactly what Walt would have wanted you to do.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Connection to Whitman:

- Visit a Local Nature Preserve: Find a spot with "uncut hair" (grass) and sit there for twenty minutes without your phone. Observe the small miracles Whitman obsessed over.

- Keep a "Multitudes" Journal: Write down three ways you contradicted yourself today. Instead of judging them, acknowledge them as parts of your "large" self.

- Listen to a Professional Reading: Find a recording of Orson Welles or Will Geer reading "Song of Myself." The sonic quality of the "yawp" is best understood through the human voice.

- Support Local Poetry: Visit an open mic night. Even if the poetry is "barbaric," appreciate the act of someone sounding their own yawp over the roofs of your city.