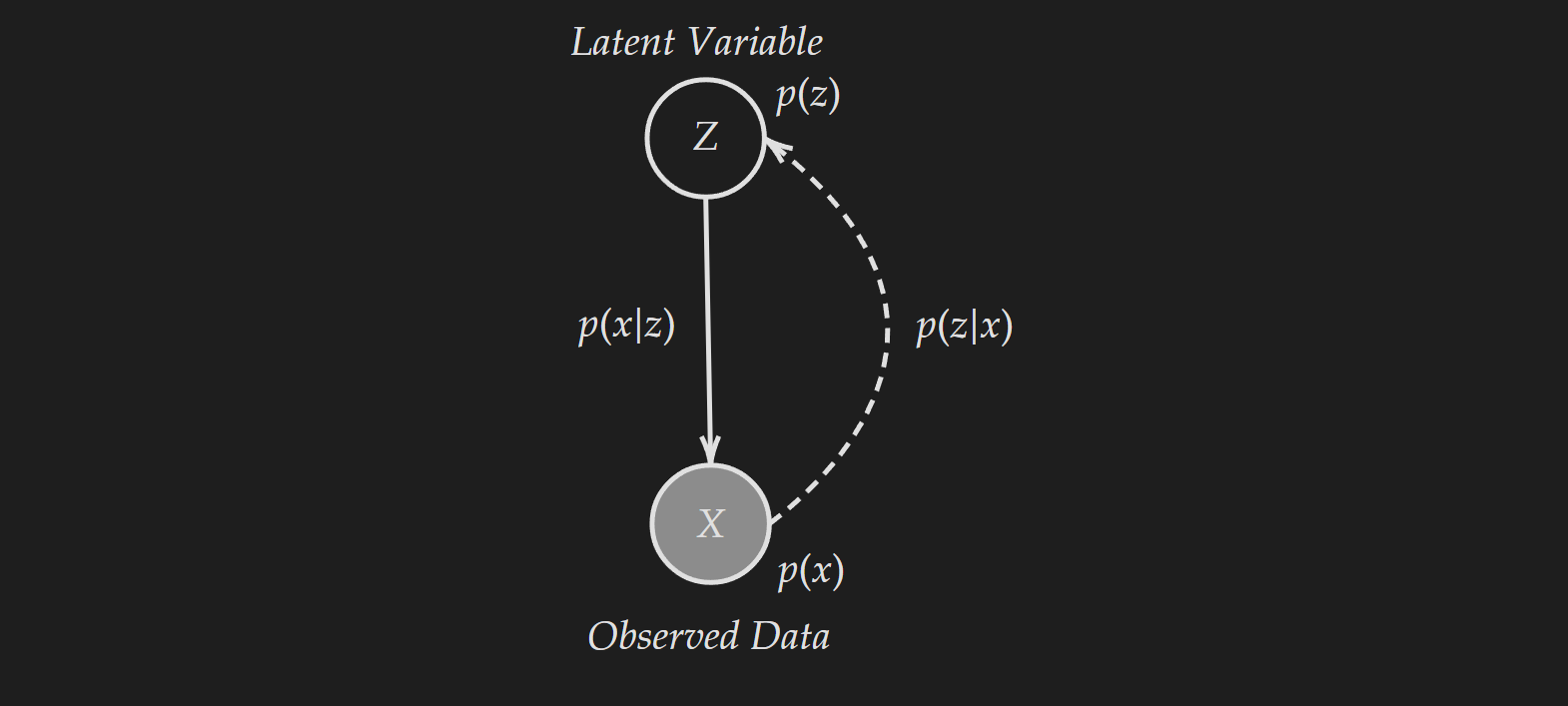

You can't see "intelligence." You can't touch "consumer confidence." You definitely can't put a ruler up against "socioeconomic status." Yet, these invisible forces drive every single dollar that moves through the global economy. Economists call these ghosts in the machine "latent variables." Basically, a latent variable model in economics is a way of measuring the stuff we can’t see by looking at the stuff we can. It sounds like magic. It’s actually just math.

Think about it. If you’re a bank trying to decide if someone will pay back a loan, you’re looking for "creditworthiness." But there is no "creditworthiness" meter you can plug into a human being. Instead, you look at their debt-to-income ratio, their payment history, and maybe how long they’ve held their job. Those are the "manifest" or observed variables. The latent variable model in economics takes those messy data points and distills them into that one invisible trait: the likelihood of default.

The Invisible Hand is Actually a Latent Variable

Adam Smith’s "invisible hand" is the most famous latent variable in history, even if he didn't have the software to model it back in the 18th century. Today, we use tools like Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Factor Analysis to give that hand a shape.

Take the concept of "Permanent Income," popularized by Milton Friedman. Friedman argued that people don't spend based on what they earned this morning. They spend based on what they expect to earn over their lifetime. You can’t observe a person’s lifetime expectation of wealth today. It’s hidden. But you can observe their current consumption of milk, cars, and housing. By using a latent variable model in economics, researchers can work backward from your grocery receipt to find your "permanent income."

Why Most Economic Forecasts Fail (And How Latent Models Help)

Most people get frustrated with economists because the "official" numbers—like GDP or the unemployment rate—feel wrong. Why? Because they are proxies. They aren't the thing itself.

A major issue in traditional econometrics is measurement error. If you just regress "Happiness" on "Income," you’re going to get a messy result because "Happiness" is impossible to measure perfectly with a 1-to-10 survey. People lie. People misinterpret the question. People had a bad cup of coffee that morning.

Latent variable models, specifically those using Latent Class Analysis (LCA), handle this by assuming that our measurements are noisy. They treat the survey answer as a "manifest indicator" of an underlying state. This is how the University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index stays relevant. It isn't just one question; it’s a cluster of indicators that reveal the latent "vibe" of the American shopper.

Real-World Example: The "Quality of Life" Trap

Governments love to talk about "Quality of Life." But how do you rank a city? Is it the number of parks? The average commute time? The air quality? If you just add those numbers up, you’re making a huge mistake because they aren't weighted equally in a human brain.

🔗 Read more: Gold Price Today Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong

Researchers use Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to see if these different indicators actually load onto a single "Quality of Life" factor. Sometimes they find they don't. You might find that "Urban Convenience" and "Environmental Health" are two separate latent variables that actually move in opposite directions. You can’t fix a city if you’re measuring the wrong ghost.

The Dark Side: Unobserved Heterogeneity

Here is a term that makes students' eyes glaze over: unobserved heterogeneity. It basically means "people are different in ways we haven't recorded."

Imagine you’re studying the impact of a job training program on wages. You see that people who took the program earn more. Great, right? Not necessarily. The people who signed up for the program might just be more "motivated" or "ambitious" than those who didn't.

- "Motivation" is a latent variable.

- If you don't account for it, you’ll give the training program credit for something the person already had inside them.

- This is called "Selection Bias," and it’s the bane of policy-making.

By using a latent variable model in economics, specifically a "Latent Variable Instrumental Variable" approach, economists can try to peel away the effect of the program from the effect of the person's innate drive. It’s like trying to weigh a cat while it's inside a carrier—you have to subtract the carrier to know if the cat is actually getting fat.

Beyond the Basics: Dynamic Latent Variables

The world isn't static. It’s a vibrating mess. That’s why we use State-Space Models. These are latent variable models that change over time. The most famous application is the "Natural Rate of Interest" (r-star).

The Federal Reserve is obsessed with r-star. It’s the interest rate that neither skips nor drags the economy. But nobody knows what it is! It’s not posted on a website. It’s a latent variable. Jerome Powell and his team use Kalman filters—a type of latent variable algorithm—to track where r-star is moving based on how inflation and GDP respond to current rates. If the Fed gets the latent variable wrong, we get a recession. No pressure.

Key Misconceptions About Latent Modeling

- It’s just "Averaging": Wrong. Averaging treats all inputs as equal. Latent models use the covariance between items to see which ones are actually the strongest "signals" of the underlying truth.

- You need thousands of data points: Not always. While more is better, the quality of the indicators matters more than the quantity. Three great questions about financial stress are better than fifty questions about what kind of shoes you buy.

- It’s only for psychology: Economics used to look down on "soft" variables. Not anymore. Behavioral economics has made the latent variable model in economics a staple for understanding things like "loss aversion" and "present bias."

Actionable Steps for Using Latent Logic in Business

If you’re running a business or analyzing a market, you can actually apply this mindset without a PhD in statistics. Stop looking at single metrics. They lie to you.

Look for clusters, not outliers.

If your "Customer Satisfaction" score is high but your "Referral Rate" is low, your latent variable—brand loyalty—is likely weak. The high satisfaction score might just be a "manifest" of people being polite, not people being fans.

Identify your "Unobserved" risks.

What are the things that could tank your project that don't show up on a spreadsheet? "Team Morale" is a latent variable. You can’t measure it directly, but you can track "Absenteeism," "Slack Channel Activity," and "Voluntary Turnover." If those indicators are shifting, your latent variable is in trouble long before the quarterly report comes out.

Stop over-weighting proxies.

A high GPA is a proxy for "Ability," but it’s a noisy one. In hiring, use multiple "manifest indicators" (tests, portfolios, interviews) to triangulate the latent trait you actually care about.

The latent variable model in economics reminds us that the most important things in life and business are the things we can’t see. We are all just trying to read the shadows on the cave wall. The math just helps us make sure we aren't hallucinating.

Next Steps for Implementation:

- Audit your KPIs: Identify which of your current metrics are "manifest indicators" and what the "latent truth" behind them actually is.

- Cross-Reference: Never rely on a single data point to define a concept like "Market Demand" or "Employee Engagement."

- Study Covariance: If you have the data, look at how different metrics move together. If two numbers don't correlate, they probably aren't measuring the same latent variable.