It was 1927. The Harlem Renaissance was hitting its stride, but Langston Hughes was about to walk into a buzzsaw. He released his second collection of poetry, Fine Clothes to the Jew, and the reaction wasn't just cold—it was radioactive.

People hated it.

Well, not everyone, but the Black middle class and the "talented tenth" elite were absolutely livid. They called him a "minstrel" and a "sewer dweller." The Pittsburgh Courier even slapped him with the title "poet low-rate of Harlem." Why? Because Hughes decided to write about the people actually living in the streets, the bars, and the basement apartments instead of the sanitized, "respectable" version of Black life that leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois wanted to project to the world.

Langston Hughes's Fine Clothes to the Jew wasn't just a book of poems. It was a manifesto of raw, unfiltered reality. It’s a messy, blues-soaked, and deeply misunderstood piece of American history that still feels strangely modern in its grit.

The Title That Still Makes People Cringe

Let's address the elephant in the room immediately. The title. To a modern ear, it sounds jarring, maybe even offensive. But context matters more than a knee-jerk reaction.

In the 1920s, the phrase "fine clothes to the Jew" was common street slang in Harlem. It referred to the practice of taking your best clothes to a Jewish pawnbroker when money was tight. It was a cycle of survival. You’d hock your Sunday suit on Monday to pay for groceries and hope like hell you could buy it back by Saturday night.

Hughes wasn't being anti-Semitic. He was being a journalist of the soul. He was capturing the specific, gritty economic reality of his neighborhood. He loved the "low-down" folks—the ones who worked all day and danced all night—and he wanted their language in his books. He refused to polish the rough edges.

The title actually comes from a line in one of the poems, "Hard Daddy," and it sets the tone for the entire collection. It’s about being broke. It’s about the struggle. It’s about the transactional nature of life when you're living on the margins.

Honestly, the controversy over the name was just the tip of the iceberg. The real beef that critics had was with the content inside.

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Blues Poetry and the "Vulgarians"

Before this book, poetry was supposed to be high-minded. It was supposed to use metaphors about Greek gods or sweeping landscapes. Hughes said, "Nah."

He pioneered "blues poetry."

He took the structure of the AAB blues stanza—where you repeat the first line twice and then hit them with a punchline or a rhyme at the end—and put it on the page. This was revolutionary. It was also, according to his critics, "trash."

The Black press at the time was obsessed with "uplift." They felt that if Black artists showed the world anything other than perfect, educated, sophisticated behavior, it would give white racists more ammunition. Then comes Langston, writing about gin, Saturday night brawls, and weary laundry workers.

He wrote about the "Elevated" train. He wrote about the "Bad Man."

A Sample of the Vibe

In poems like "Brass Spittoons," he focuses on the men cleaning up after white patrons in hotels. It’s not a pretty job. It’s gross. But Hughes finds a weird, spiritual dignity in the work. He connects the "cleanliness" of the job to a kind of religious ritual.

"A bright bowl of closed-up golden pain."

That’s how he described a spittoon. It’s heavy stuff.

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

But the elite didn't see the beauty. They saw a young man "wallowing" in the mud. They wanted sonnets; Hughes gave them the 12-bar blues. He basically told the Black aristocracy that their desire to be "respectable" was a form of self-hatred. He believed that the "low-down" folks were the ones who actually kept Black culture alive because they weren't trying to act like white people.

Why the Critics Went Nuclear

The backlash against Fine Clothes to the Jew was so intense it actually hurt Hughes's feelings, though he rarely admitted it. The New York Amsterdam News called the book "a redundant pounding of the same old themes." They were exhausted by his focus on the working class.

There was this huge tension in the Harlem Renaissance between "High Art" and "Folk Art."

- The Elites: Wanted to prove Black people were "civilized" through classical forms.

- Hughes: Wanted to prove Black people were "beautiful" exactly as they were, sweat and all.

He was accused of being a "racial traitor." Think about that. One of the greatest poets in history was being told he was hurting his race because he wrote about common people. It’s a debate we still see today in music and film—do artists have a "responsibility" to show only the best parts of a community? Hughes's answer was a resounding no.

He believed that honesty was the only way to achieve real freedom. If you're hiding who you are to please a critic, you're still a slave to their opinion.

The Structure of the Collection

The book isn't just a random pile of poems. It’s organized into sections that feel like a walk through a city.

- Blues: The heart of the book. Rhythmic, repetitive, and deeply emotional.

- Railroad Avenue: The sounds of the tracks and the streets.

- Levee Land: A nod to the Southern roots of the people who migrated North.

- Feet of Jesus: The spiritual side, though even his religious poems have a bit of a weary, street-smart edge to them.

He uses "Negro Folk Idiom." This means he wrote how people actually talked. He didn't fix the grammar. He didn't clean up the slang. He captured the cadence of the Great Migration.

You’ve gotta realize how radical this was. At the time, most poets were still trying to sound like Keats or Shelley. Hughes was trying to sound like a guy at a bar in Memphis or a woman hanging laundry in a Harlem alleyway. It was punk rock before punk rock existed.

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

The Lasting Legacy: Was He Right?

Looking back from nearly a century later, it’s clear Hughes won the argument.

Nobody remembers the names of the critics who called him "proletarian" or "vulgar." But everyone knows Langston Hughes. Fine Clothes to the Jew is now studied in every major university as a masterpiece of American modernism.

It paved the way for everything. Without this book, you don't get the gritty realism of Gwendolyn Brooks. You don't get the rhythmic genius of the Beat poets. You arguably don't get the lyrical depth of hip-hop, which relies heavily on the same "folk idiom" and "street reporting" that Hughes pioneered.

He taught us that there is nothing "low" about the lives of ordinary people. The struggle to pay rent, the joy of a Saturday night dance, and the heartbreak of a lost lover are all "high art" if they are told with enough truth.

Key Takeaways for Readers Today

If you're diving into this collection for the first time, keep a few things in mind so you don't get lost in the old-school slang.

- Read it aloud: These poems were meant to be heard. If you read them silently, you miss the rhythm. If you read them out loud, you’ll hear the music.

- Look past the title: Don't let the 1920s terminology distract you from the universal themes of poverty and resilience.

- Observe the "unsaid": Hughes says a lot in what he leaves out. His poems are often short, leaving the reader to feel the weight of the silence between the lines.

- Check the history: Research the "Great Migration." Understanding why all these people were in Harlem in the first place makes the poems hit way harder.

Actionable Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

To truly appreciate what Hughes was doing with this controversial masterpiece, you should engage with the material beyond just reading the text on a screen.

- Listen to 1920s Blues: Find recordings of Bessie Smith or Ma Rainey. These were the women Hughes was listening to while he wrote. When you hear the "AAB" pattern in their singing, go back and look at the poems in the "Blues" section of the book. The connection will click instantly.

- Compare with "The Weary Blues": Read his first book alongside Fine Clothes to the Jew. You’ll see how he got bolder and less concerned with pleasing the white audience or the Black elite.

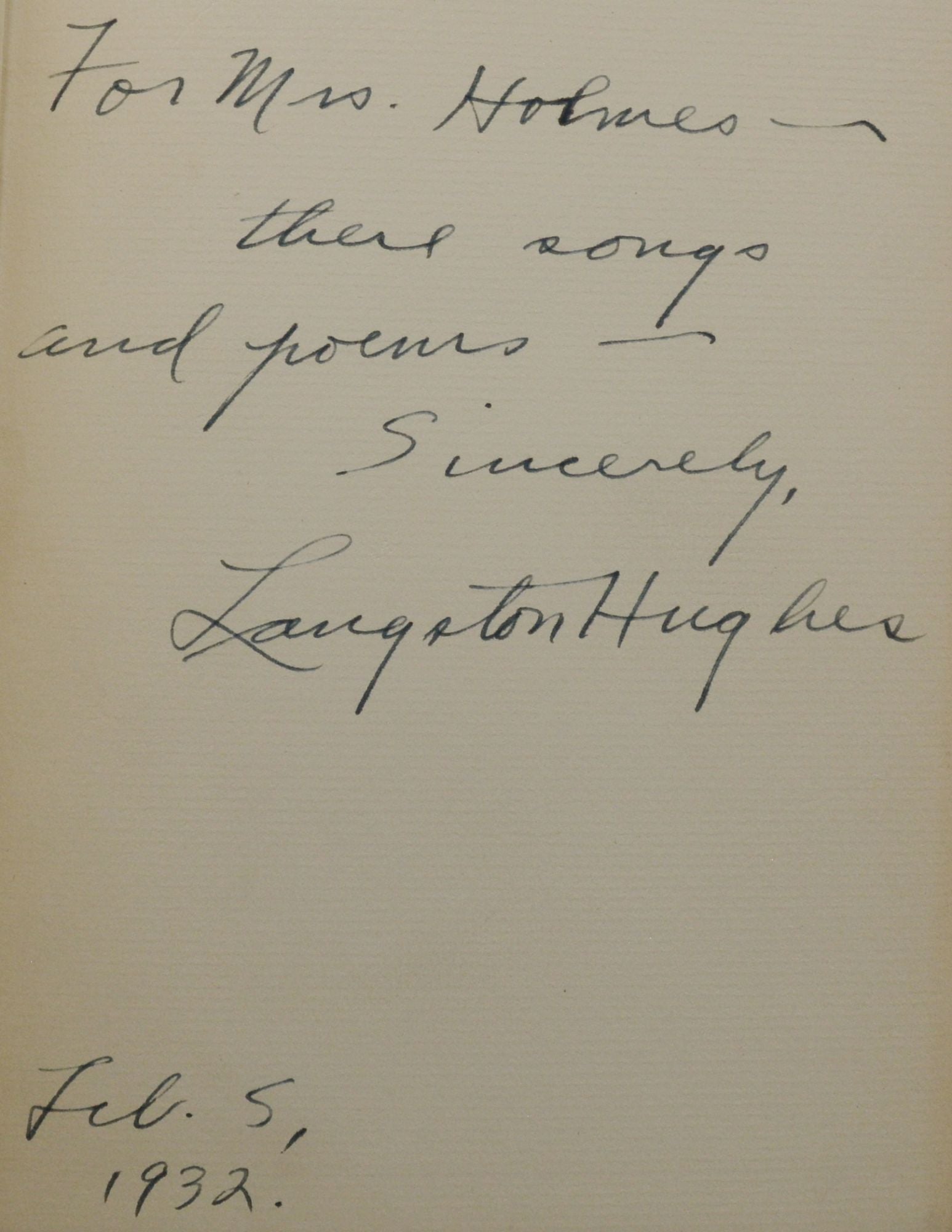

- Visit the Schomburg Center (Virtually or In-Person): The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem holds massive archives related to Hughes. Seeing the original manuscripts and the letters he received (both hate mail and fan mail) provides a visceral sense of the era.

- Write a "Blues Poem": Try using the AAB structure to write about a modern struggle—like a dead phone battery or a long commute. It’s harder than it looks to make it soulful. This exercise helps you realize the technical skill Hughes used to make his "simple" poems work.

Langston Hughes didn't write for the critics. He wrote for the people who pawned their "fine clothes" to survive another week. He gave them a voice that the world couldn't ignore, even if the world tried to hush him up at first. That's why we’re still talking about it. That's why it still matters. Through the lens of 1927 Harlem, he showed us the universal human condition.

He didn't need to be "respectable" to be great. He just needed to be honest.