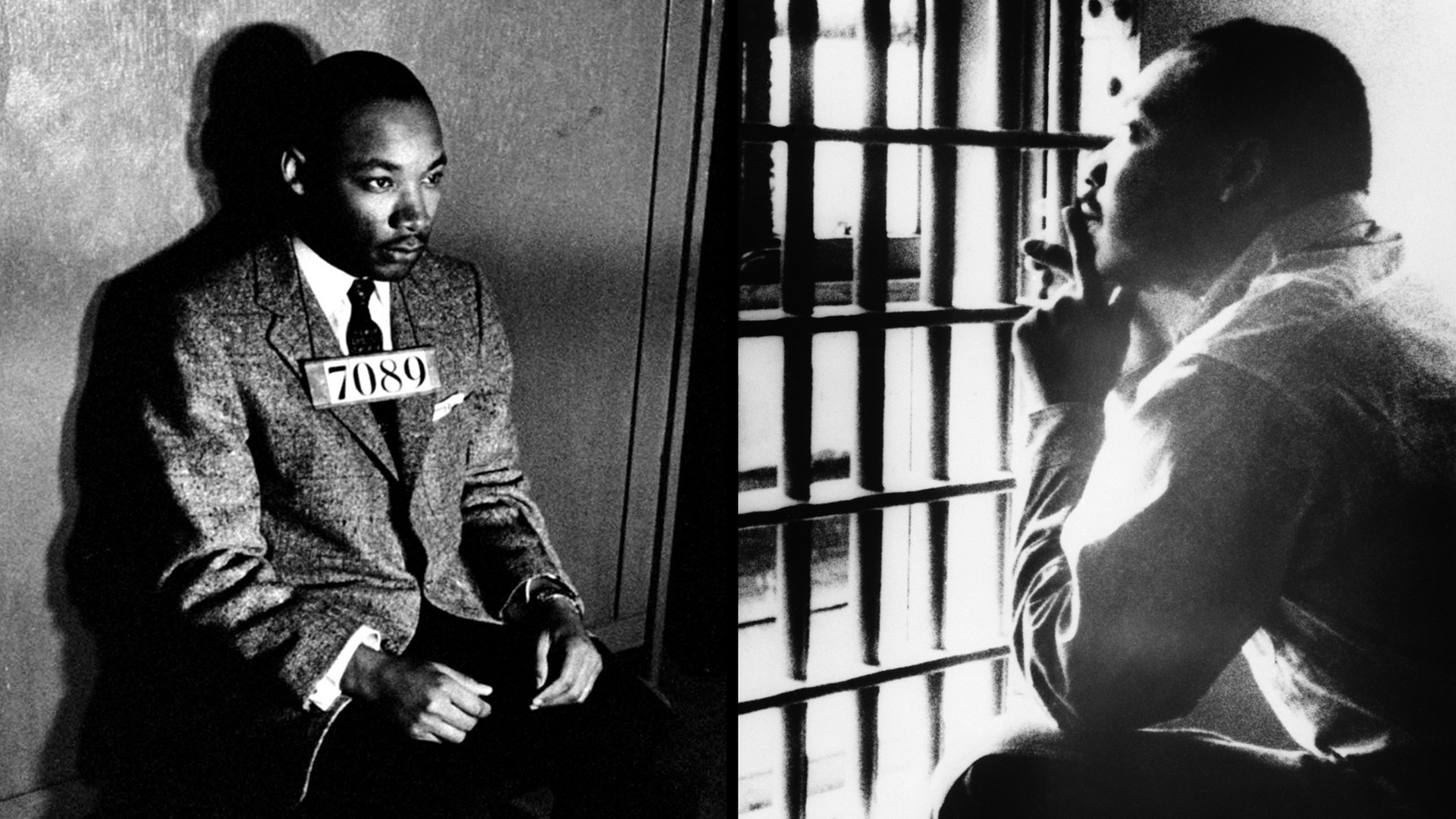

Martin Luther King Jr. was sitting on the floor of a narrow, dark jail cell in 1963 when he started scribbling on the margins of a newspaper. He didn't have fancy stationery. He didn't have a desk. He just had a stinging sense of betrayal. He had been arrested for protesting without a permit in Alabama, part of the Birmingham Campaign, and while he was sitting there, he read an op-ed in the local paper.

Eight white clergymen—men who were supposedly on the side of morality—basically told him to "wait." They called his actions "unwise and untimely." They wanted him to stop the "extreme" stuff and just let the courts handle it. King’s response, now known as the Letter from Birmingham Jail, wasn't just a polite "thank you for your feedback." It was a surgical, intellectual, and deeply emotional dismantling of the idea that justice can afford to be patient.

Honestly, it’s one of the most important pieces of writing in American history. But if you only read the "I Have a Dream" speech, you're missing the sharp edge of King’s philosophy. This wasn't a speech about a fuzzy future; it was a manifesto written in the heat of a legal and social battle.

The Myth of the "Good Time" for Progress

One of the biggest misconceptions about the Letter from Birmingham Jail is that it was written to his enemies. It wasn't. It was written to his "allies." That’s why it feels so relevant even in 2026. King was targeting the "moderate" who prefers order to justice.

He wrote that the "Negro's great stumbling block" wasn't the KKK or the blatant bigot. It was the white moderate who is more devoted to "order" than to justice. Think about that for a second. It's a heavy critique. He was saying that someone who agrees with your goals but hates your methods is actually more of a hurdle than someone who hates your goals.

King argued that "wait" almost always meant "never." He listed out the things he had seen—the lynchings, the police brutality, the 20 million people "smothering in an airtight cage of poverty." When you read those sections, the sentence structure gets long and breathless. He’s overwhelming the reader with the reality of life in the Jim Crow South. He basically says: You want me to wait? We’ve been waiting for 340 years.

Defining Just vs. Unjust Laws

How do you justify breaking the law? This is where King goes full philosopher. He knew he was being called a lawbreaker. He didn't deny it. Instead, he reached back to St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas to explain the difference between a "just" law and an "unjust" law.

💡 You might also like: Teamsters Union Jimmy Hoffa: What Most People Get Wrong

- A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God.

- An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law.

He gave a very practical example: any law that uplifts human personality is just, and any law that degrades it is unjust. Segregation was unjust because it distorted the soul. But he went further. He pointed out that a law can be "just on its face" but "unjust in its application." For example, it’s fine to have a law requiring a permit for a parade. But when that law is used to deny people their First Amendment rights to peaceably assemble and protest, the law becomes a tool of oppression.

He didn't just stop at Christian theology. He brought in Jewish philosopher Martin Buber’s "I-it" vs "I-thou" concept. Segregation, King argued, treated people as "its"—things to be manipulated—rather than "thous"—human beings with dignity. It’s a dense, brilliant section that makes it impossible to dismiss him as just an agitator. He was a scholar.

Why Birmingham?

People often ask why King chose Birmingham. He called it the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its record of brutality was "notoriously terrible." There had been so many unsolved bombings of Black homes and churches that people nicknamed it "Bombingham."

King’s organization, the SCLC, had been invited by local leaders like Fred Shuttlesworth. They didn't just show up to start trouble. They went through a four-step process:

- Collection of facts to determine if injustices exist.

- Negotiation.

- Self-purification (workshops on nonviolence).

- Direct action.

They tried negotiating. The city's economic leaders promised to remove humiliating signs from stores. They didn't. They lied. King realized that "tension" was necessary. He didn't see "tension" as a bad word. He wanted to create a "nonviolent tension" that would force a community to confront the issue.

The "Extremist" Label

The clergymen called King an extremist. At first, he was offended. Then, he leaned into it.

📖 Related: Statesville NC Record and Landmark Obituaries: Finding What You Need

He looked at history. Was not Jesus an extremist for love? Was not Amos an extremist for justice? Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel? Was not Martin Luther an extremist? He even brought up Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson. He basically flipped the script. The question isn't whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice?

It’s a masterclass in rhetoric. He took a slur used against him and turned it into a badge of honor by aligning himself with the very figures his critics claimed to admire.

The Disappointment with the Church

Perhaps the most heartbreaking part of the Letter from Birmingham Jail is King's open grief over the organized church. He expected the white church to be one of his strongest allies. Instead, many were "outright opponents," and even more were "cautious" behind the "anesthetizing security of stained-glass windows."

He remembered how the early Christians were world-shakers. They weren't afraid of being "disturbers of the peace." But the 1960s church, in his view, had become a "weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound." He warned that if the church didn't recapture its sacrificial spirit, it would lose its "authenticity" and be dismissed as an "irrelevant social club."

Looking at modern trends in 2026 regarding church attendance and social justice, King’s warning feels almost prophetic. He wasn't trying to destroy the church; he was trying to save it from its own complacency.

Fact-Checking the History

It’s vital to remember that King didn't write the whole thing at once. He started on the margins of the Birmingham News. When those were full, he moved to scraps of paper brought to him by a "friendly" Black trustee in the jail. Eventually, he was allowed a legal pad.

👉 See also: St. Joseph MO Weather Forecast: What Most People Get Wrong About Northwest Missouri Winters

His lawyers, including Clarence Jones, smuggled the scraps out. It was then compiled and edited at the SCLC office. The fact that such a cohesive, logically sound, and historically referenced document was produced under those conditions is staggering. He didn't have a library. He had his memory.

Actionable Takeaways from King’s Philosophy

Reading the Letter from Birmingham Jail shouldn't just be an academic exercise. It offers a framework for handling conflict and seeking change in any era.

- Audit your "Wait": King challenges us to look at the areas where we tell others (or ourselves) to wait for a "more convenient season." Usually, that season never comes. Progress requires "the tireless efforts of men willing to be coworkers with God."

- Distinguish Order from Justice: True peace is not the absence of tension, but the presence of justice. If you are keeping the peace by ignoring an underlying problem, you aren't actually creating peace. You're just managing a facade.

- Engage in Self-Purification: Before the Birmingham protesters went out, they asked themselves: "Are you able to accept blows without retaliating?" and "Are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?" Any movement or personal change requires internal discipline before external action.

- Speak to the "Moderate" Middle: King knew that the extremist opposition wasn't going to change overnight. His real work was trying to move the people who were "lukewarm." Influence happens when you challenge those who agree with you in principle but are paralyzed by comfort.

The letter was eventually published in The Atlantic, Christian Century, and Liberation. It didn't immediately change the minds of the eight clergymen—most of them remained defensive for years—but it changed the world. It provided the moral backbone for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

King ended the letter with a hope that the "dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away." We aren't fully there yet. But the letter remains a map for how to navigate the storm.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

- Read the original "A Call for Unity": To understand the letter, you have to read the statement by the eight clergymen that prompted it. It provides the context for King’s specific rebuttals.

- Trace the Theological Roots: Look up "Personalism," the philosophical school King studied at Boston University. It explains why he valued "human personality" so highly in his definitions of justice.

- Visit the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute: If you're ever in Alabama, seeing the actual jail cell door and the locations mentioned in the letter turns the text into a physical reality.