It was April 16, 1963. Martin Luther King Jr. wasn't sitting in a comfortable study or a library. He was in a cramped, dark cell in Alabama, writing on the margins of a newspaper because he didn't have any actual stationery. Honestly, it’s one of the most raw documents in American history. When we talk about a letter from a Birmingham jail, we often treat it like a dusty relic from a history book, but the reality was much more intense. It was a response to "A Call for Unity," a statement published by eight white clergymen who basically told King to slow down. They called his protests "unwise and untimely."

Imagine that.

👉 See also: Is Georgia Under a State of Emergency? What You Actually Need to Know Right Now

You’re fighting for your basic humanity, and the "moderates" tell you to wait for a better time. King’s response wasn't just a polite rebuttal. It was a surgical dismantling of white moderate complacency. He was tired of being told "Wait," which he famously noted almost always meant "Never."

The "Outside Agitator" Myth and Why it Matters

One of the first things King hits in the letter from a Birmingham jail is this idea that he was an "outsider" coming in to stir up trouble. It’s a tactic people still use today. You see it in news cycles every time there's a protest—critics claim the people complaining aren't even from the community.

King shut that down immediately.

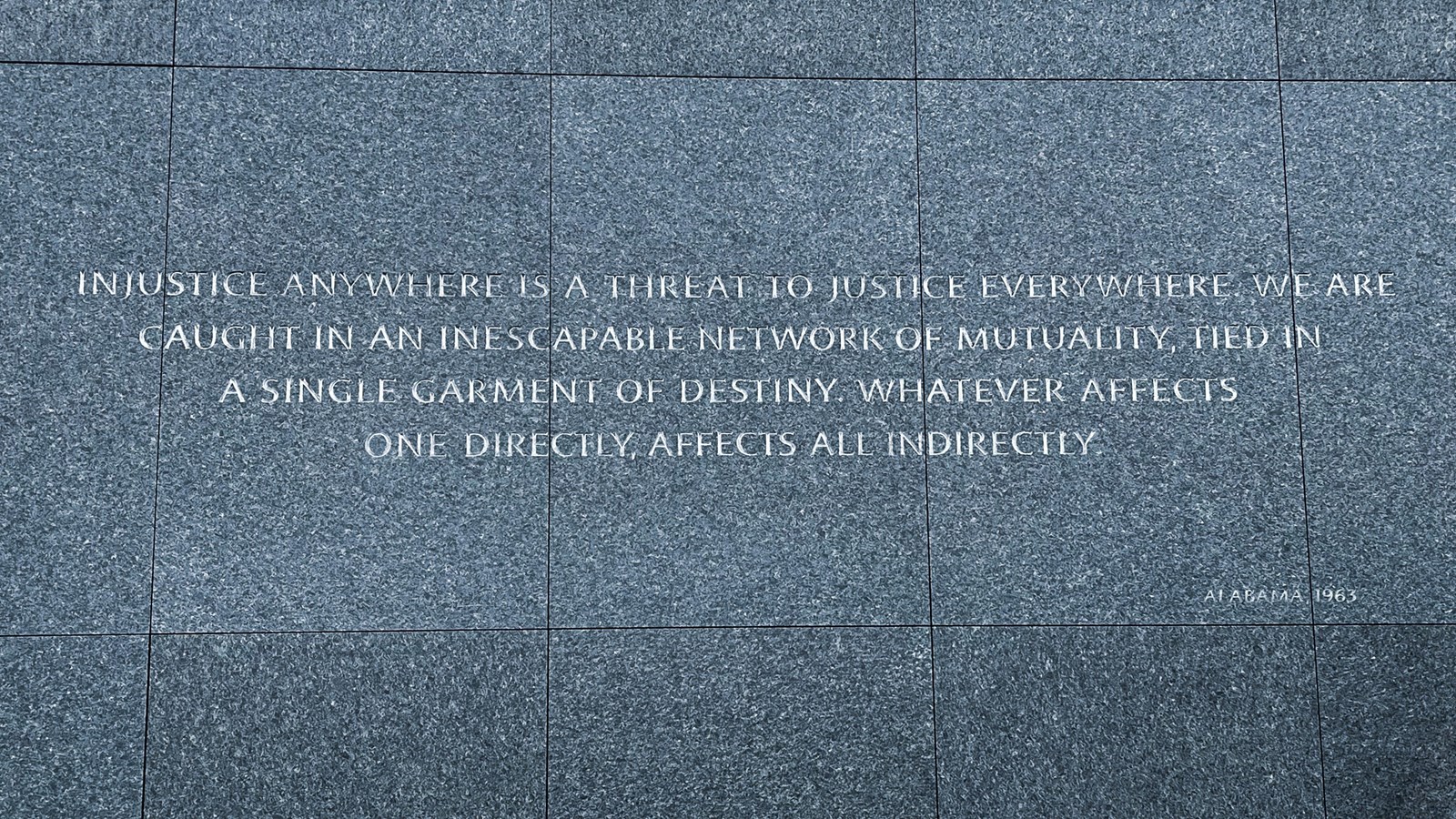

He pointed out that he was the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and had been invited by the local affiliate. But then he went deeper. He gave us that legendary line: "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere." He argued that we are caught in an "inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny." If you live in the United States, you aren't an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

It's a powerful thought. It suggests that looking the other way when someone else’s rights are violated isn't just a moral failing; it's a logical one. You can’t insulate yourself from the rot of injustice just because it’s happening in a different zip code.

The Four Steps of a Nonviolent Campaign

People often think nonviolence is just about being "nice" or "passive." It’s actually the opposite. It’s a calculated, aggressive confrontation with the status quo. In his letter from a Birmingham jail, King breaks down exactly how they approached the Birmingham campaign. It wasn't random.

- First, you collect the facts to determine if injustices exist. (In Birmingham, the facts were everywhere—the bombings of Black homes and churches were the highest in the nation).

- Second, you try negotiation. People forget this. The movement leaders tried to talk to the city fathers. It failed.

- Third, you go through "self-purification." This is the part most people skip. They held workshops to ask themselves: "Are you able to accept blows without retaliating?" "Are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?"

- Finally, you take direct action.

The goal of direct action—the sit-ins, the marches—wasn't to cause a riot. It was to create a "crisis" and foster a "tension" that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront. He didn't fear the word tension. He actually leaned into it. He wanted a constructive, nonviolent tension that would force people to the table.

The White Moderate: King’s Biggest Frustration

This is the part of the letter from a Birmingham jail that still makes people uncomfortable today. Most people assume King was most angry at the KKK or the blatant racists like Bull Connor.

🔗 Read more: Donald Trump Rigged Election: What Most People Get Wrong

He wasn't.

He was more disappointed in the "white moderate." He wrote that the "Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom" wasn't the White Citizen's Councilor, but the moderate who is more devoted to "order" than to "justice." These were the people who preferred a "negative peace," which is just the absence of tension, over a "positive peace," which is the presence of justice.

Think about that for a second.

How many times do we see people today say, "I agree with your goal, but I don't like your methods"? King heard that every single day. He realized that the person who tells you to wait for a "more convenient season" is often a bigger obstacle than the person who hates you openly. The person who hates you is an enemy you can see. The person who "supports" you but constantly polices how you demand your rights is a weight that pulls you down slowly.

Just vs. Unjust Laws

How do you justify breaking the law? This was a big sticking point for the clergymen who criticized him. They pointed out that the protesters were breaking ordinances.

King’s logic here is brilliant. He draws on St. Thomas Aquinas and Socrates. He argues that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law.

- An unjust law is any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.

- Segregation is unjust because it "distorts the soul and damages the personality."

- An unjust law is a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself.

He famously argued that one has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. But—and this is a huge "but"—he said you have to do it openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the legal penalty. You don't break the law and run. You break the law to show the community the law is wrong, and you accept the jail time to prove your respect for the idea of law itself.

The Myth of Time

There’s this weird idea that things just "get better" over time. King hated this. He called it the "strangely irrational notion that there is something in the very flow of time that will inevitably cure all ills."

Time is neutral.

It can be used either destructively or constructively. He felt that the "people of ill will" were using time much more effectively than the "people of good will." He feared that the church and the "moderates" were sitting back, waiting for a miracle, while the forces of oppression were working overtime. Progress doesn't roll in on the wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts of people willing to be co-workers with God.

Why the Church Failed Him

King was a minister. He loved the church. But in the letter from a Birmingham jail, he is incredibly harsh on the religious establishment. He looked at the beautiful churches and wondered, "What kind of people worship here? Who is their God?"

He was disappointed that the church had become a "social club" rather than a force for change. In the early days of Christianity, he noted, the church was powerful. Christians were "God-intoxicated." They were "disturbers of the peace" who changed the world. By 1963, he felt the church had become a "weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound."

It’s a warning that still rings true for any institution that prioritizes its own comfort and tax-exempt status over standing up for the marginalized.

The Birmingham Context

To really understand the letter from a Birmingham jail, you have to remember what Birmingham was like in 1963. It was probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its police commissioner, Eugene "Bull" Connor, was a man who didn't mind using fire hoses and attack dogs on children.

The "clergymen" King was responding to weren't necessarily "bad" guys in the traditional sense. They were "moderates." They wanted things to change, but they wanted it to happen through the courts and through "proper channels."

But King knew the "proper channels" were rigged.

✨ Don't miss: NY Times on Israel: What Most People Get Wrong

The courts were slow, and the local government was hostile. If they hadn't marched, if they hadn't filled the jails, the world wouldn't have looked. The letter was a way to bypass the local filters and speak directly to the conscience of the nation. It was smuggled out of the jail in pieces and eventually published in magazines like The Christian Century and The Atlantic Monthly.

Moving Beyond the "Wait"

So, what do we actually do with this today? King’s letter isn't just a list of grievances; it's a manual for social change. If you're looking to apply these lessons, start here:

- Audit your "Order vs. Justice" balance. Are you more annoyed by a loud protest or by the reason the people are protesting in the first place? If the "disruption" bothers you more than the "injustice," you might be the "white moderate" King was talking about.

- Recognize that negotiation requires leverage. You can't just ask for rights from people who benefit from you not having them. You have to create a situation where negotiation is the only logical path forward.

- Stop waiting for the "right time." There is no such thing. The "right time" to do the right thing is always right now.

- Check your "Outsider" bias. When you hear about a struggle in another city, another country, or another neighborhood, don't dismiss it as "not my problem." Everything is connected.

The letter from a Birmingham jail remains a foundational text because the human tendency to prefer a quiet life over a just one hasn't changed. We still have people who want "peace" without "righteousness." King's words serve as a permanent check on our collective conscience. They remind us that silence is a choice, and usually, it's a choice to support the status quo.

Read the letter again. Not the snippets in a textbook, but the whole thing. It’s long, it’s dense, and it’s arguably the most important piece of literature written in the 20th century. It challenges the reader to move from being a "spectator" to being a "participant" in the struggle for human dignity.

If you want to understand the modern world, you have to understand the tension King was trying to create. He wasn't looking for a fight; he was looking for a resolution that actually meant something. He knew that you can't heal a wound that you're too afraid to uncover. The letter was his way of pulling back the bandage so the light and air of truth could finally get in.

Actionable Next Steps

- Read the Original Document: Go to the Stanford University King Institute and read the full, unedited text. It takes about 20 minutes and hits differently than the highlights.

- Identify Modern "Unjust Laws": Look at current local ordinances or national policies. Ask if they apply equally to those who made them versus those who must follow them.

- Engage with Local Advocacy: Find a group in your city that is currently in the "negotiation" or "direct action" phase of a local issue. See how they are applying (or ignoring) King’s four-step process.

- Practice Constructive Tension: In your own workplace or community, identify a problem everyone is ignoring for the sake of "peace." Bring it up. Don't be afraid of the discomfort; use it to move toward a solution.