If you’ve ever walked through the "darker" sections of a university library, you’ve probably seen the name. Donatien Alphonse François de Sade. The Marquis de Sade. Most people know the name because it gave us the word "sadism," but honestly, the actual books are a whole different level of disturbing. Justine ou les malheurs de la vertu isn't just a book; it’s a philosophical wrecking ball. Written in 1787 while Sade was rotting in the Bastille, it’s basically the story of a girl who tries to be "good" and gets absolutely destroyed for it.

It’s brutal.

We usually like stories where the hero wins. Or, at the very least, where their suffering means something. Sade doesn't give you that. He flips the script. In Justine, the more virtuous the protagonist acts, the worse her life gets. It’s a cynical, pitch-black look at the Enlightenment, and even 200 years later, it feels dangerously modern.

The Plot Nobody Wants to Admit They Read

The story follows two sisters, Justine and Juliette. After their parents die and they're left penniless, they take very different paths. Juliette decides that morality is a scam and goes into a life of crime and debauchery. She ends up rich and powerful. Justine, on the other hand, decides she’s going to remain "virtuous."

She fails. Hard.

Throughout Justine ou les malheurs de la vertu, she is kidnapped, enslaved, accused of crimes she didn't commit, and physically abused by almost every person she meets. Priests, nobles, outlaws—they all treat her like a toy. The kicker? Every time she escapes one horror, she runs straight into another because she insists on trusting people or following "moral laws." Sade isn't just writing smut here; he's making a point about power. He’s arguing that the world doesn't care about your soul. It cares about who has the whip.

It's a tough read. Not just because of the graphic nature, but because it feels like a personal attack on the idea of justice.

✨ Don't miss: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Why Sade Wrote It (And Why It Got Him Jailed)

Sade wasn't just some guy with a weird hobby. He was a nobleman who hated the hypocrisy of the French aristocracy. He wrote three different versions of this story. The first was a short novella called Les Infortunes de la vertu. Then came the 1791 version, which is the most famous one. Finally, he went full-throttle with La Nouvelle Justine in 1797, which was even more explicit.

Napoleon Bonaparte was so offended by it that he ordered Sade’s arrest. Sade spent the last 13 years of his life in an asylum because of this book. Think about that. Most writers today worry about getting "canceled" on social media. Sade got locked in a cell with no windows for his prose.

The Philosophical Trap

People often mistake this for simple pornography. It’s not. It’s "philosophy in the bedroom." The villains in the book—people like the monk Father Clement or the nobleman Bressac—don't just commit crimes. They give long, ten-page speeches explaining why they do it. They argue that nature is cruel, so humans should be cruel too.

- They claim pity is a weakness.

- They argue that "virtue" is a social construct used by the weak to control the strong.

- They suggest that since we all die anyway, the only thing that matters is immediate pleasure.

It’s basically Nietzsche before Nietzsche, but with way more blood and way less filter. Sade uses Justine as a literal punching bag to prove his philosophical points. It’s unsettling because he’s actually a very good debater. You find yourself reading these horrific justifications and thinking, "Wait, is he right?" and then immediately feeling like you need a shower.

The "Anti-Enlightenment" Statement

During the 1700s, guys like Voltaire and Rousseau were telling everyone that humans were naturally good. They thought education and reason would solve everything. Sade looked at that and laughed. Justine ou les malheurs de la vertu is his middle finger to the Enlightenment.

He portrays a world where the "Reason" of the powerful is used to justify the exploitation of the weak. In the book, the legal system doesn't protect Justine; it’s the tool used to frame her. The church doesn't offer her sanctuary; it’s a den of predators. It’s a total inversion of everything the French Revolution was supposed to stand for.

🔗 Read more: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Honestly, it’s cynical. But if you look at history—the Terrors of the Revolution, the world wars, the systemic collapses of the 20th century—Sade’s bleak view of human nature starts to look a lot more accurate than Rousseau’s "noble savage" theory.

Is It Even Art?

This is the big debate. Critics like Simone de Beauvoir have written extensively on Sade. In her famous essay Must We Burn Sade?, she argues that while his work is monstrous, it’s also essential because it forces us to confront the darkest parts of the human psyche.

You can’t just ignore the book. It’s too influential. You see its fingerprints in modern horror movies, in the transgressive fiction of Chuck Palahniuk, and even in the "grimdark" aesthetic of shows like Game of Thrones. Sade pushed the boundaries of what could be put on a page so far that he basically created a new category of literature.

But let’s be real: it’s a slog. The repetition is intentional—Sade wants to exhaust you. He wants you to feel as hopeless as Justine. The sentence structure is often dense, typical of the 18th century, but the subject matter is so visceral it breaks through the "stuffy" old-fashioned language.

The Ending (Spoiler Alert)

The way it ends is almost a joke. After years of suffering, Justine finally reunites with her sister, Juliette. Juliette is now wealthy, happy, and thriving because she embraced vice. Just as it looks like Justine might finally find some peace, she gets struck by lightning and dies.

Lightning.

💡 You might also like: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

Sade is basically saying that even the universe itself hates her "virtue." It’s the ultimate "f*** you" to the reader. There’s no redemption. No heaven. Just a random, violent end to a miserable life. It’s the kind of ending that makes you want to throw the book across the room, which is exactly what Sade wanted.

How to Approach the Text Today

If you’re going to read Justine ou les malheurs de la vertu, don't go in looking for a fun time. You won't find one. Go in looking for a historical document of a man who was pushed to the absolute edge of sanity.

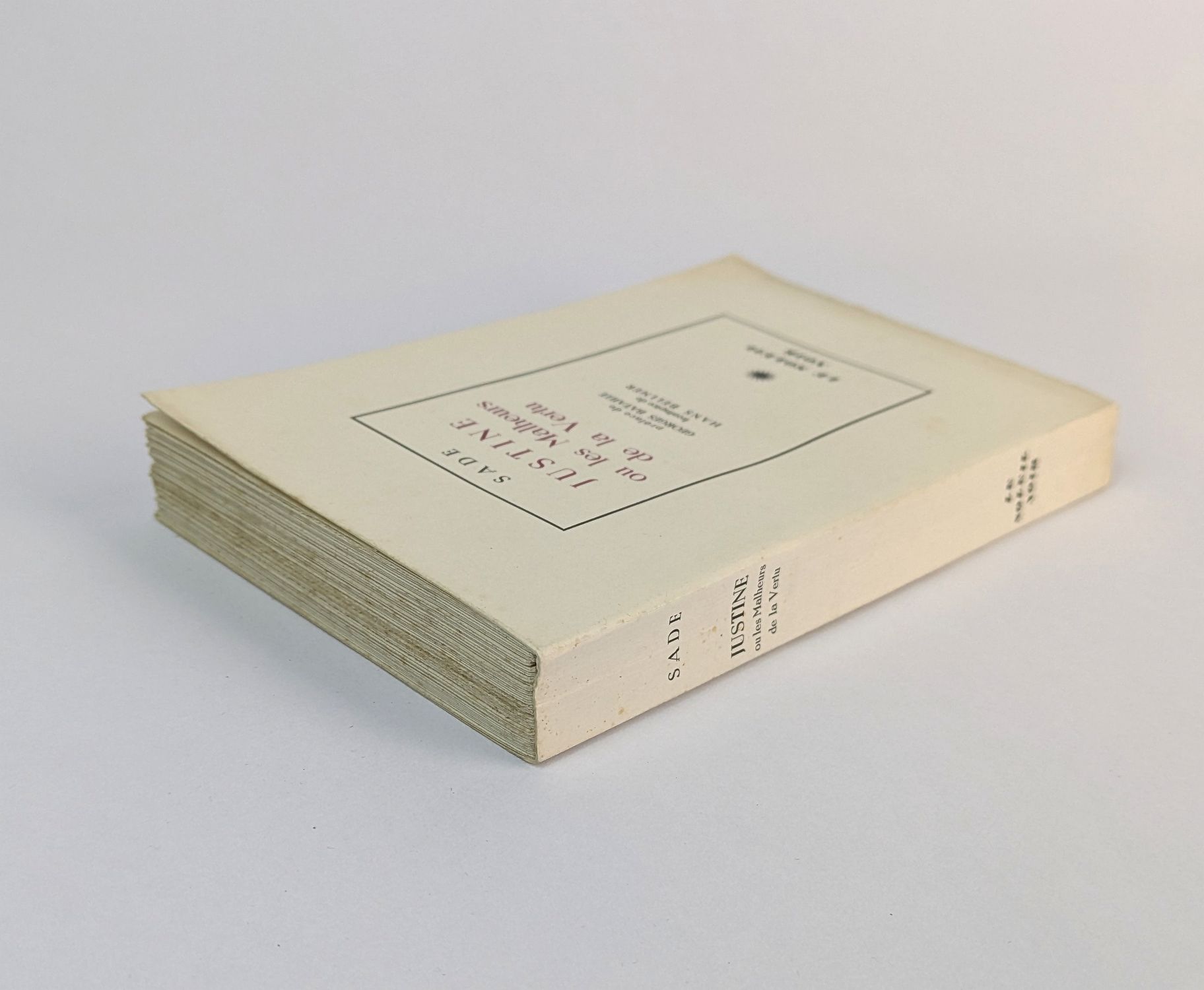

- Pick a good translation. The Penguin Classics version is usually the gold standard because it handles the philosophical rants with enough clarity that you don't get lost in the 18th-century "thees" and "thous."

- Read it alongside the history. Context is everything. Understanding that Sade wrote this while the French Revolution was literally chopping heads off outside his window makes the violence in the book make a lot more sense.

- Don't binge it. It’s heavy. It’s depressing. It’s designed to make you uncomfortable.

Real Actionable Takeaways

If you’re interested in literature, philosophy, or the history of transgressive art, here’s how to actually engage with this material without losing your mind:

- Compare the Sisters: If you read Justine, you almost have to read Juliette (the companion novel). Seeing the contrast between the two sisters is the only way to get the full scope of Sade’s "system."

- Contextualize the "Sadean Hero": Look at modern villains in film and literature. Notice how many of them use "Sadean logic"—the idea that power is the only truth. It helps you spot this specific type of nihilism in pop culture.

- Check out the 1969 film: There’s a movie adaptation by Jesús Franco. It’s... weird. It captures the "Euro-sleaze" vibe of the late 60s, but it also shows how the story has been sanitized and warped over time.

- Explore the "Divine Marquis" Legacy: Research the Surrealist movement. Artists like Salvador Dalí and writers like Georges Bataille worshipped Sade. They saw him as a liberator of the imagination. Understanding their take helps you see the "art" behind the "filth."

Ultimately, Justine ou les malheurs de la vertu remains one of the most controversial books ever written because it refuses to lie to us. It suggests that being a good person doesn't guarantee a good life. It’s a bitter pill to swallow, but that’s exactly why it hasn't been forgotten. It challenges our most basic assumptions about how the world works, and that’s what great—if horrifying—literature is supposed to do.

***