It is a Tuesday in 1834. Charlotte Elliott is sitting in a room in Brighton, England, feeling completely useless. Everyone else in her family is busy at a church bazaar, working hard, being "productive" Christians. Charlotte? She is paralyzed. Not just by the chronic illness that kept her bedridden for much of her life, but by a crushing sense of spiritual inadequacy. She feels like she has nothing to offer God because she has no strength.

In that moment of total vulnerability, she grabs a pen. She doesn't write a complex theological treatise. She writes a poem.

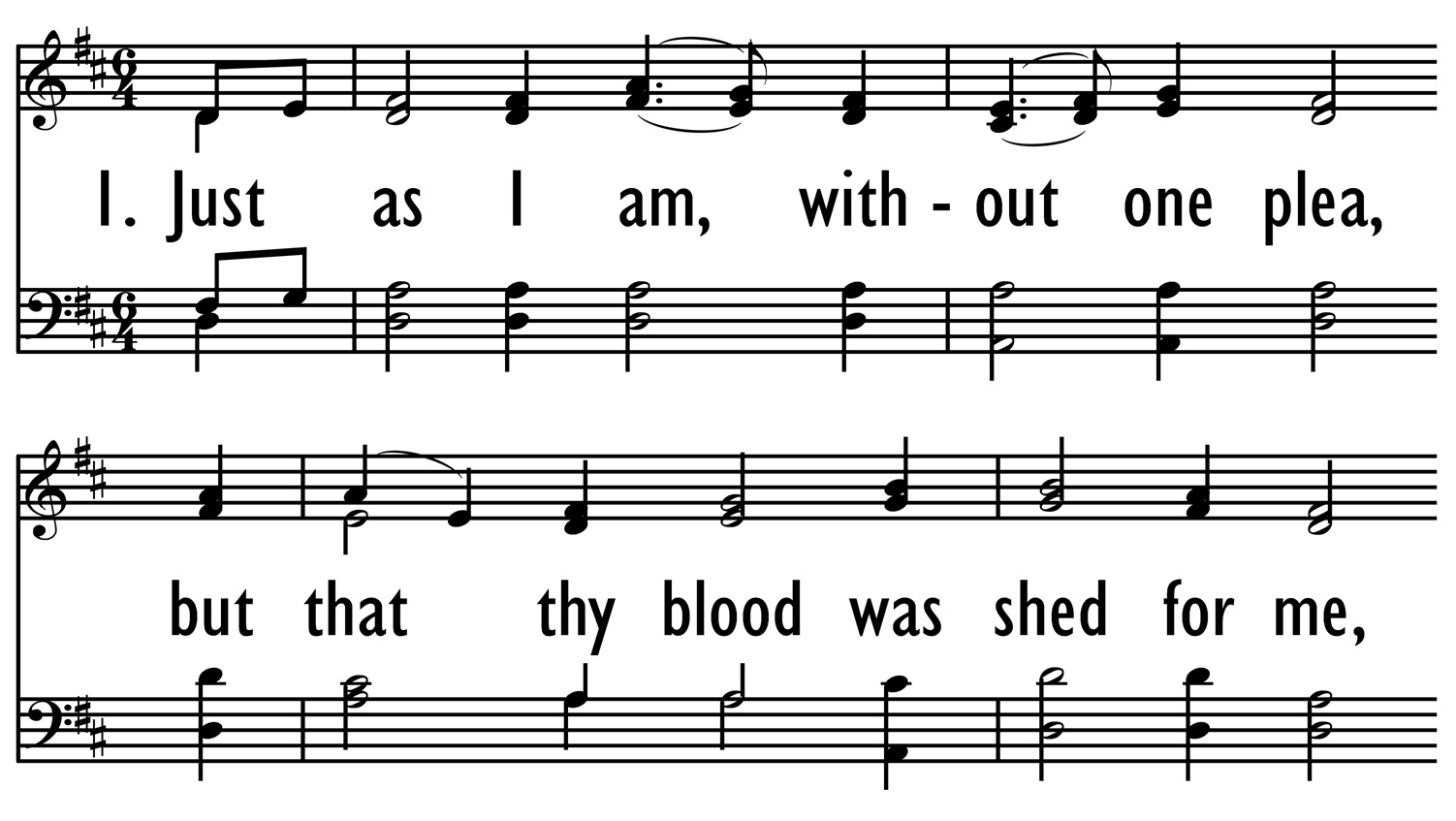

That poem became the song Just As I Am Without One Plea, and honestly, it’s arguably the most influential hymn in the history of the modern church. If you grew up in a Baptist, Methodist, or Presbyterian church, you’ve heard it. You’ve probably stood through fifteen stanzas of it while a preacher waited for someone to walk down the aisle. But there is a reason this specific set of lyrics has outlasted almost every other Victorian-era hymn.

It’s because it’s a song about being a mess.

The Woman Behind the Words

Charlotte Elliott wasn't a "professional" songwriter. She was an invalid. For years, she struggled with the bitterness of her physical limitations. A few years before she wrote the hymn, she met a Swiss evangelist named César Malan. He asked her if she was at peace with God. Charlotte, being human and frustrated, snapped at him. She told him she wanted to clean up her life and become a better person before she dealt with the "religious stuff."

Malan’s response changed everything. He told her, "Come to him just as you are."

It took years for that to sink in. When it finally did, during that lonely Tuesday at home, she penned the words that would eventually define the "altar call" for the next two centuries. People often think of Just As I Am Without One Plea as a song of triumph, but it’s actually a song of surrender. It is the sound of someone giving up on the idea of self-improvement.

Why Just As I Am Without One Plea Changed Everything

Billy Graham. You can't talk about this song without mentioning the man from North Carolina.

Actually, Billy Graham’s entire ministry was practically soundtracked by this hymn. He used it at almost every crusade he ever held. He once said that the reason they chose it was because it was the most "biblically sound" invitation they could find. It didn't demand that the listener bring a resume. It demanded they bring their "tossed about" souls and "conflicts."

Think about the structure for a second. Most hymns of that era were wordy. They were dense. They used flowery language that required a dictionary. But Elliott’s lyrics are startlingly simple.

✨ Don't miss: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

- "Without one plea."

- "But that thy blood was shed for me."

- "I come."

It’s staccato. It’s direct. It mirrors the heartbeat of someone who is exhausted. When you look at the musical setting—most commonly the tune Woodworth by William Bradbury—it’s repetitive. Some critics say it’s boring. They’re wrong. It’s hypnotic. It’s designed to lower the barriers of the ego.

The Theology of the "Messy"

There’s a specific line in the hymn that hits harder than the others: "Fightings and fears within, without."

Most religious music in the 1800s focused on the glory of God or the beauty of creation. Elliott went internal. She talked about the "dark blot" of the soul. This was radical. She was admitting, in a very public way, that faith isn't a linear path of getting better and better. It’s a constant return to a starting point.

The song Just As I Am Without One Plea works because it validates the human experience of failure.

In a modern context, we call this "vulnerability." In 1834, they just called it "confession." But the psychological impact is the same. It tells the listener that they don't have to "fix" their addiction, their temper, or their doubt before they are allowed to show up.

A Cultural Staple Beyond the Church

It isn't just for Sunday mornings.

The song has been covered by everyone from Johnny Cash to Alan Jackson. Cash’s version is particularly haunting. When you hear a man with a voice that sounds like gravel and old regrets sing "tossed about with many a conflict, many a doubt," you realize this isn't a churchy song. It’s a blues song that happens to be about Jesus.

It has appeared in movies, in literature, and at funerals of world leaders. It’s the universal "reset button."

Interestingly, Charlotte Elliott lived to be 82. She wrote hundreds of other hymns, but none of them ever touched the hem of this one. She reportedly received thousands of letters during her lifetime from people who said her words had saved their lives. Her brother, a clergyman, once said that in his entire career, he had done less good than his sister did with this single poem.

🔗 Read more: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

The Controversy of the Altar Call

Not everyone loves the way the song has been used.

Some theologians argue that the "endless" looping of Just As I Am Without One Plea during evangelical crusades was a form of emotional manipulation. They argue that the minor-to-major shifts in the melody are designed to trigger a psychological response, forcing people into a decision they might not be ready for.

Is there truth to that? Maybe. Music is a tool, and tools can be used in many ways.

But even if you strip away the big stadium lights and the weeping crowds, the core of the song remains. It’s a solo. It’s one person standing in a room, realizing they are enough exactly as they are. That is a message that transcends the mechanics of an altar call. It’s a message about the inherent value of a human being, independent of their "pleas" or "works."

What Most People Miss About the Lyrics

Check out the third verse. Most people gloss over it.

"Just as I am, though tossed about with many a conflict, many a doubt."

We live in an age of certainty. Everyone on social media is certain about their politics, their diet, and their lifestyle. Elliott was writing about doubt as a permanent fixture of the journey. She didn't say "Just as I am, now that I’ve figured it all out." She said the doubt is actually part of the "coming."

If you’re struggling with the feeling that you don't "fit" into a spiritual or social box, this song is actually your anthem. It’s the ultimate "misfit" song.

Applying the Lesson of Charlotte Elliott

How do you actually use the "Just As I Am" philosophy in 2026?

💡 You might also like: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

It starts with an audit of your own "pleas." We all have them. "I’ll be happy when I lose 10 pounds." "I’ll be worthy when I get that promotion." "I’ll start that project when I have more experience."

Charlotte Elliott’s life teaches us that the "waiting for readiness" phase is a trap. If she had waited until she felt healthy or "useful" to write her poetry, we wouldn’t have the hymn. She wrote from the center of her weakness.

Stop waiting for the "clean" version of yourself to show up.

Whether you are religious or not, there is a profound psychological freedom in the phrase Just As I Am Without One Plea. It is the rejection of the performance-based life. It is the acceptance of the present moment, flaws and all.

Actionable Insights for the "Just As I Am" Mindset

- Identify your "Before" statements. Write down the things you told yourself you need to accomplish before you can be at peace.

- Embrace the "Tossed About" state. Understand that doubt isn't the opposite of faith or confidence; it’s the environment where they grow.

- Practice radical presence. In your next high-stress situation, remind yourself that you are there "without one plea"—you don't need to justify your space in the room.

- Listen to the variations. Go find the 1950s Billy Graham recordings, then listen to Johnny Cash’s version. Notice how the meaning shifts from a corporate call to a personal confession.

The enduring legacy of this song isn't in the hymnal. It’s in the fact that two hundred years later, a person can still sit in a room, feel like a total failure, and find a path forward by simply stopping the struggle to be perfect.

Sometimes, the most "productive" thing you can do is admit that you have nothing to bring to the table. And that, surprisingly, is exactly when the table becomes yours.

Next Steps:

Read the original 1834 text of Charlotte Elliott’s poem to see the verses that are often cut from modern hymnals, particularly those focusing on the physical "poor, wretched, blind" aspects that reflected her own illness. Then, try writing your own "Just As I Am" list—not of goals, but of current, messy realities you are choosing to accept today.