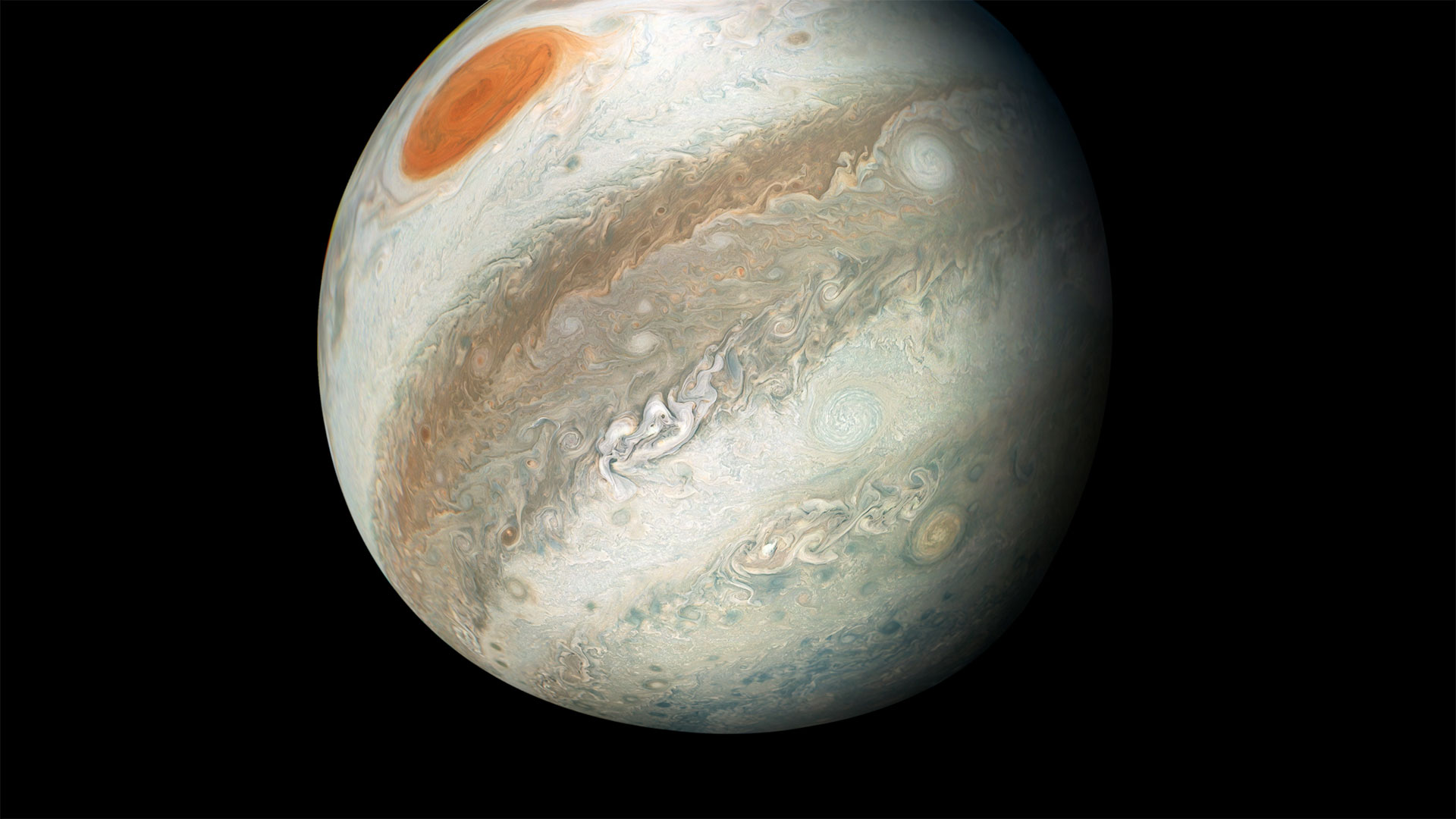

Jupiter is a monster. Honestly, there is no other way to describe a planet so big you could fit 1,300 Earths inside it and still have room for dessert. But before 2016, our mental image of the gas giant was kinda... flat. We had the Voyager shots and the Cassini flyby photos, which were great, but they mostly showed us the "face" of the planet from a distance. Then NASA sent a titanium-armored box spinning into a polar orbit. Now, juno spacecraft pics of jupiter have fundamentally broken our understanding of what a planet is even supposed to look like.

It isn't just about high resolution. It’s about the perspective. Juno gets screamingly close—skimming just a few thousand miles above the cloud tops during its perijove (close approach) maneuvers. When those first raw files started hitting the servers at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), scientists weren't just excited. They were confused. The north pole wasn't the striped, orderly world we saw in textbooks. It was a chaotic, blue-tinted mosh pit of cyclones the size of Texas.

The JunoCam Secret: It’s Actually Your Camera

Here is a weird fact: JunoCam wasn’t originally part of the "core" science mission. NASA basically added it as an outreach tool, thinking it would be cool for the public to see some snaps. Because of that, the mission handles the data differently than any other flagship project. The raw, "meat-colored" linear scans are dumped onto a public server, and a global community of amateur image processors—people like Kevin M. Gill, Seán Doran, and Gerald Eichstädt—turn them into the psychedelic masterpieces you see on your feed.

Without these "citizen scientists," the juno spacecraft pics of jupiter we obsess over wouldn't exist in their current form. These folks spend hundreds of hours de-warping the images, adjusting the color curves to highlight atmospheric depth, and stitching frames together. It’s a marriage of hardcore data and digital artistry. It makes the planet feel less like a distant rock and more like a living, breathing marble of ammonia and water ice.

Why the Great Red Spot Looks Different Now

We’ve been staring at the Great Red Spot for 350 years. We thought we knew it. But when Juno flew directly over it, the images revealed a terrifying level of verticality. It isn’t just a flat swirl; it’s a towering wedding cake of storm clouds.

- The storm’s roots go deep. Like, really deep. Juno’s Microwave Radiometer (MWR) found that the Great Red Spot extends about 200 to 300 miles (300 to 500 kilometers) down into the planet.

- The colors are shifting. Recent photos show the spot getting smaller and more orange-ish rather than deep red.

- High-altitude hazes are visible. You can see "fluffy" white clouds of ammonia ice casting actual shadows on the deeper crimson layers below.

Seeing a shadow on Jupiter is a trip. It gives you a sense of scale that numbers just can't communicate. When you see a cloud shadow that is fifty miles long, you realize you're looking at a weather system that could swallow Earth whole without burping.

💡 You might also like: Google Cloud Next 2026: What Really Happened in Las Vegas

The Marble-Like Swirls Aren't Just Pretty

If you look at the "Marble Movie" or the close-up shots of the Jovian atmosphere, you see these intricate, paisley-like patterns. These are Folded Filamentary Regions (FFRs). Basically, they are areas where the intense jet streams of Jupiter get tangled up.

Scott Bolton, the principal investigator for Juno, has often pointed out that the planet’s interior is just as weird as the surface. Before these images and the gravity data that accompanied them, many thought Jupiter might have a small, rocky core. Now? It looks like the core might be "fuzzy" or dilute—mixed into the metallic hydrogen layer. The juno spacecraft pics of jupiter provide the visual context for these invisible mysteries. The turbulence we see on the surface is just the "skin" of a much deeper, more violent engine.

It’s Not Just Jupiter Anymore: Ganymede and Io

Juno was supposed to be dead by now. The original mission was shorter, but the spacecraft is a tank. NASA extended the mission, allowing it to perform flybys of the Galilean moons.

The shots of Ganymede were the first close-ups we’d had in twenty years. Then came Io. Io is the most volcanic place in the solar system, and the recent Juno images show a world that looks like a moldy pizza covered in literal lakes of lava. In one image from early 2024, you can see a dual-plume eruption catching the sunlight on the horizon. It’s haunting. It looks like a CGI render from a big-budget sci-fi movie, but it’s a real place, currently burning and sulfurous, millions of miles away.

The "Face" in the Clouds and Pareidolia

People love finding patterns. In 2023, during Juno's 54th close flyby, one image went viral because it looked exactly like a screaming face or a stylized "Jovian Ghost." This is pareidolia—our brains trying to make sense of chaos.

But there’s a scientific side to the "art." The reason those shapes look so organic is that the fluid dynamics of Jupiter’s atmosphere mimic things we see on Earth. The same physics that governs cream stirring into coffee or the way smoke curls from a candle is happening on a planetary scale. Juno captures this perfectly because it uses a "push-broom" sensor. As the spacecraft spins, the camera takes strips of the planet, which are then reconstructed. This motion sometimes adds to the surreal, stretched-out feel of the vistas.

Lightning and "Mushballs"

One of the most mind-blowing things discovered via Juno’s imaging and sensors is the "shallow lightning." On Earth, lightning comes from water clouds. On Jupiter, Juno saw flashes coming from clouds containing an ammonia-water solution.

Scientists call the resulting hailstones "mushballs." These are chunks of ammonia and water that get heavy, fall through the atmosphere, and suck up nitrogen. You can’t see a mushball in a photo, but you can see the distinctive, small-scale "pop-up" clouds that signify where these storms are brewing. They look like tiny white dots against the dark belts. Except, they aren't tiny. They're the size of cities.

How to Explore the Data Yourself

If you’re tired of the low-res re-shares on social media, you can actually go to the source. NASA’s JunoCam gallery is a goldmine. You can download the "RDR" (Reduced Data Record) files or the "raw" PNGs.

- Check the Perijove numbers: Each close flyby is numbered. Perijove 58 and 60 have some of the most stunning "low-altitude" shots of the northern hemisphere.

- Look for the "True Color" vs. "Enhanced Color": Enhanced color is what most people see—it boosts the contrast to show the storms. True color is much more muted, looking like a creamy, tan-and-brown marble. Both are valid; they just tell different stories.

The Reality of Jupiter’s Radiation

Every time Juno takes a picture, it’s a miracle the camera still works. Jupiter has the most intense radiation environment in the solar system (outside of the Sun). The electronics are housed in a solid-top radiation vault made of titanium.

Even with that armor, high-energy particles constantly pelt the sensors. If you look closely at some of the unprocessed juno spacecraft pics of jupiter, you’ll see "noise" or bright specks. That’s not dust; that’s radiation hitting the camera’s CCD. The mission is a race against time. Eventually, the radiation will fry the "eyes" of the spacecraft, or the orbital decay will force a de-orbit into Jupiter's atmosphere to protect the moons from Earth-microbe contamination.

What’s Next for the Mission?

Juno is currently in its "Extended Mission" phase, which runs through September 2025—or until the hardware gives up the ghost. The orbits are getting shorter. The focus is shifting more toward the ring system and the moons.

We are learning that Jupiter isn't just a big ball of gas; it's a complex system that acts like a mini-solar system. The rings, which are faint and made of dust kicked off the smaller moons, have been captured in stunning detail by Juno’s Stellar Reference Assembly (SRA), usually used for navigation.

✨ Don't miss: Is H2O a Compound? Why Most People Get the Basics Wrong

Actionable Insights for Space Enthusiasts

If you want to stay on top of the latest Jovian discoveries without drowning in jargon, here is how you do it:

- Follow the processed feeds: Keep an eye on the Mission Juno website. This is where the community uploads their work. It is updated almost daily after a perijove.

- Use the metadata: When looking at a photo, check the "Altitude" tag. Anything under 10,000 km is considered a "close-up." These are the shots where you can see the individual "waves" in the ammonia clouds.

- Watch the Moons: The mission is transitioning. We are going to see more of Europa and Io in the coming months. These shots are rarer and often more scientifically valuable because we have so few of them.

- Understand the "Blue" Jupiter: If you see a photo of Jupiter that looks bright blue, remember that it's likely a shot of the poles. Jupiter’s poles are naturally bluer than the equatorial belts, but many artists enhance this to show the temperature differences in the cyclones.

Jupiter is a reminder that the universe doesn't have to make sense to be beautiful. It's a chaotic, radioactive, swirling mess of gas that happens to look like a van Gogh painting. The Juno mission has given us a front-row seat to that chaos, and frankly, we’ll be staring at these pictures for the next fifty years trying to figure out what we’re actually looking at.

The most important thing to remember when you see these images is that they aren't static. Jupiter is changing. The storms move, the Red Spot shrinks, and the "mushballs" fall. It’s a dynamic world, and we’re lucky enough to have a camera right in the middle of it.