Jules Verne was kind of a freak for facts, which is hilarious because he wrote a book about a giant hole in the planet where dinosaurs still roam. If you pick up a Journey to the Center of the Earth novel today, you aren't just reading a dusty piece of 1864 sci-fi. You're basically stepping into the brain of a man who was obsessed with the emerging (and often wrong) science of the Victorian era. It’s wild. Most people think they know the story because they saw the Brendan Fraser movie or that 1959 classic with the accordion music, but the actual book is way weirder and much more grounded in actual mineralogy than you’d expect.

Verne didn't just wake up and decide to invent a hollow world. He was reading guys like Charles Lyell and Sainte-Claire Deville. He wanted to know if the Earth's core was actually a molten furnace or if, maybe, it was cool enough for a grumpy German professor to hike through.

The Grumpy Genius and the Secret Code

Let’s talk about Otto Lidenbrock. Honestly, he’s one of the most stressful characters in literature. He’s a professor in Hamburg who finds a runic manuscript by a 16th-century Icelandic alchemist named Arne Saknussemm. This is where the Journey to the Center of the Earth novel really kicks off. It’s not an accidental fall into a pit; it’s a calculated, obsessive quest. Lidenbrock drags his nephew, Axel, who is basically the "everyman" who just wants to stay home and marry his girlfriend, Graüben.

They head to Iceland. They find a guide named Hans, who is the MVP of the entire story because he never panics, even when they’re about to die of thirst or get blasted out of a volcano.

The Science Verne Actually Got Right (Sorta)

People love to dunk on Verne for the "Hollow Earth" theory. But back in the 1860s, the scientific community was genuinely debating the internal temperature of the planet. Some thought it increased by one degree for every seventy feet you went down. If that were true, Lidenbrock and Axel would have been turned into human stir-fry before they even cleared the crust.

Verne used the character of Lidenbrock to argue against the "central heat" theory. He used real geological terms—gneiss, schist, quaternary deposits—to make the impossible feel plausible. When they descend into the crater of Snæfellsjökull, it’s not magic. It’s a grueling, dark, claustrophobic hike.

💡 You might also like: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

The prose isn't always flowery. Sometimes it's just lists of rocks. It’s gritty.

That Insane Underground Ocean

The turning point of the Journey to the Center of the Earth novel is the Lidenbrock Sea. Imagine finding an ocean so big it has its own weather patterns. Huge clouds. Electric storms. This isn't just a big puddle; it’s a subterranean ecosystem.

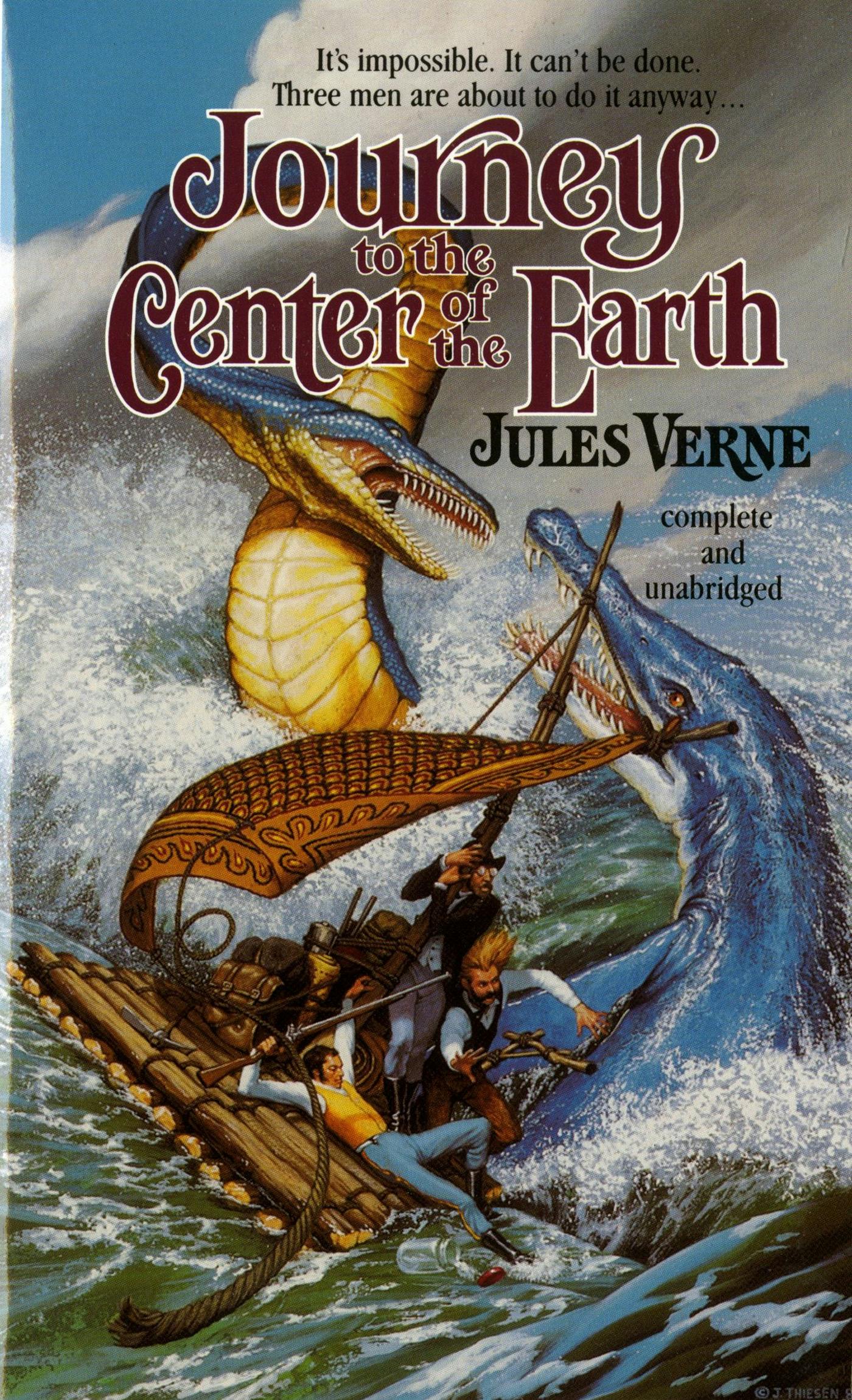

This is where the book shifts from a geological textbook to a fever dream. They see giant mushrooms—Lycoperdon giganteum—that are forty feet tall. They build a raft. They watch a fight between an Ichthyosaurus and a Plesiosaurus. This scene is iconic because, at the time, these fossils were being pulled out of the ground in Europe, and people were terrified/fascinated by them. Verne brought them back to life.

It’s worth noting that Axel’s narration gets increasingly frantic here. He’s convinced they’re going to die. He’s probably right to feel that way.

The Mystery of the Giant Human

One of the most debated parts of the book is the sighting of the "Shepherd of the Mastodons." As they wander through a forest of prehistoric plants, they see a twelve-foot-tall humanoid creature herding a bunch of elephants.

📖 Related: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

Is it a ghost? A giant? An evolutionary anomaly?

Verne never really explains it. Lidenbrock and Axel just run away. It’s one of those rare moments where the "expert" narrator has no answer, and it adds this layer of genuine horror to the adventure. It suggests that the center of the Earth isn't just a museum of the past; it's a place where the rules of biology just stopped caring.

Why the Journey to the Center of the Earth Novel Isn't What You Remember

If you've only seen the movies, you're probably expecting a lot of "falling through the floor" and "sliding down crystals." The book is much slower. It’s a slow burn. It’s about the psychological toll of being miles underground with no sun.

Axel experiences intense bouts of vertigo and hallucinations.

The ending is also famously chaotic. They don't just climb back out the way they came. They get caught in a volcanic eruption at Stromboli, Italy. They literally ride a slab of rock on top of a column of magma. It’s scientifically impossible, obviously, but it’s a masterclass in pacing. They go in through the cold of Iceland and get spat out by the heat of the Mediterranean.

👉 See also: Tim Dillon: I'm Your Mother Explained (Simply)

Common Misconceptions About Verne’s Vision

- The Earth is hollow: Not exactly. Verne suggests there are massive caverns and pockets, but he doesn't necessarily subscribe to the "whole planet is a shell" theory that was popular with guys like John Cleves Symmes Jr.

- It’s a kids' book: Only if your kid likes reading about the chemical composition of air. It’s actually quite dense and aimed at the 19th-century "gentleman scientist" demographic.

- They find a civilization: Nope. No lizard people. No Atlantis. Just raw, terrifying nature and some very large animals.

How to Actually Read This Book Today

Don't just grab the first copy you see at a thrift store. A lot of the early English translations of the Journey to the Center of the Earth novel are absolute garbage.

The 1871 Griffith and Farran translation, for example, is notorious for changing the characters' names (calling Lidenbrock "Professor Hardwigg") and literally deleting entire sections of scientific dialogue because the translator thought they were boring. If you read that version, you aren't really reading Verne; you're reading a Victorian remix.

Look for the William Butcher translation or the one by Frederick Paul Walter. They keep the "weirdness" intact and respect the fact that Verne was trying to be a serious hard-sci-fi writer.

Key Takeaways for Your Next Reading

- Check the Map: Keep a map of Iceland and Italy open. Following their path from Snæfells to Stromboli makes the scale of the trip feel much more real.

- Focus on the Trio: Watch how Hans, the guide, acts as the anchor. Without him, the two "intellectuals" would have died in the first three chapters. It’s a great commentary on the value of practical skill vs. academic theory.

- Note the Darkness: Pay attention to how Verne describes light. From the Ruhmkorff lamps to the strange electrical glow of the inner sea, the book is obsessed with how we see in the dark.

If you want to understand where modern sci-fi comes from, you have to look at the Journey to the Center of the Earth novel. It’s the blueprint. It’s the bridge between the old "travelogues" of the 1700s and the hard science fiction of the 20th century. It reminds us that no matter how much we map the surface, there's a lot of terrifying, unknown space right beneath our boots.

To get the most out of the experience, compare the descriptions of the subterranean fossils to the actual skeletal reconstructions found in the Paris Museum of Natural History during Verne's time. It shows just how much "homework" he did before putting pen to paper.