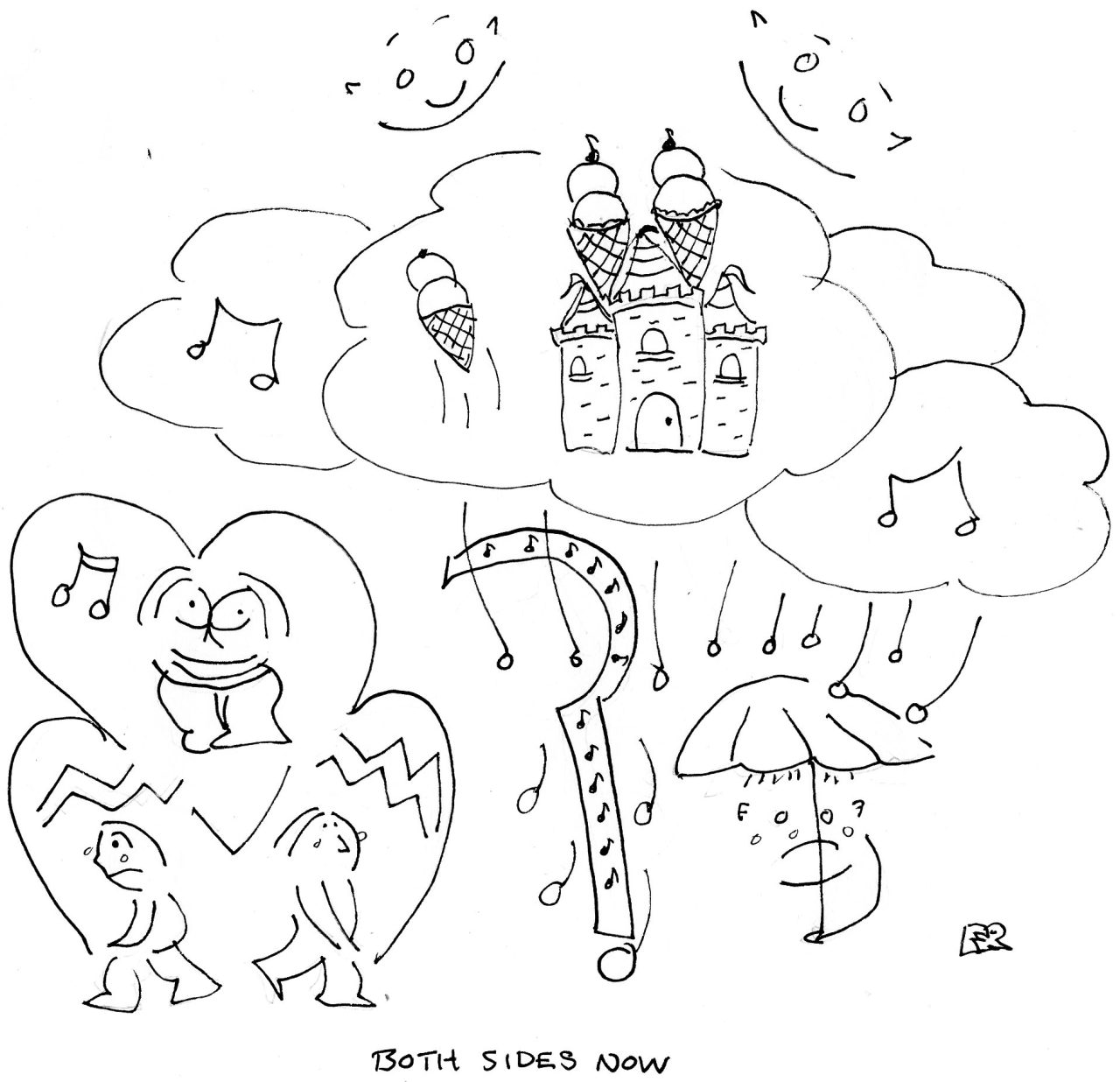

Architecture is a funny thing because we usually think of it as static. Bricks, mortar, some glass, and a roof that hopefully doesn't leak when the January sleet hits. But Joni Mitchell changed how we look at the concept of "home" when she bought a small, unassuming property in Matala or later, her legendary estate in Bel Air. Most people hear the song "Both Sides, Now" and think about clouds or lost love, but for those of us obsessed with the intersection of art and living spaces, the house both sides now represents a literal and figurative shift in how a creator occupies a physical world.

It’s personal.

Back in the late 1960s, Mitchell wasn't just writing hits; she was building a sanctuary. When she moved into her Laurel Canyon home—the one famous for the Ladies of the Canyon era—it wasn't just a building. It was a hub. Imagine Graham Nash, David Crosby, and Stephen Stills just hanging out in a living room that smelled like oil paints and California dust. That house had two sides: the public face of a burgeoning folk icon and the private, messy reality of a woman trying to figure out if she even wanted the fame she was winning.

The Dual Reality of Creative Spaces

We often talk about "work-life balance" like it’s a scale. It isn't. It’s more like a house with a very thin wall. Mitchell’s homes have always reflected this duality. Take her property in Sunshine Coast, British Columbia. It’s rugged. It’s isolated. It’s built of stone and wood and looks like it grew out of the moss.

On one side, you have the architectural intent. The "both sides" of a house often refer to the contrast between the interior comfort and the exterior wildness. Joni has spoken about how the stone walls of her Canadian retreat provided a literal barrier against the pressures of the music industry. You can’t hear the critics when you’re staring at the tide coming in.

But then there's the other side. The side that involves the upkeep, the loneliness of remote living, and the realization that a house is just a box unless you’re actually living in it. People often romanticize the "artist in a cabin" trope, but Joni’s reality was more complex. She was painting. She was composing on a grand piano that had to be hauled into a space that probably wasn't designed for it.

Why the Matala Caves Mattered

Before the mansions, there were the caves. If we’re talking about the house both sides now philosophy, we have to look at Matala, Crete. In the early 70s, Joni lived in a literal cave. Talk about minimalist. On one side, you had the ultimate freedom—no rent, no walls, just the Mediterranean Sea. On the other, you had the harshness of the elements and the "hippie" lifestyle that eventually became its own kind of cage.

She wrote "Carey" there. She lived the "both sides" of poverty and spiritual wealth. It’s a perspective most modern homeowners, obsessed with granite countertops and smart doorbells, totally miss. A house doesn't need to be fancy to be a masterpiece. It just needs to be honest.

Laurel Canyon and the Myth of the Open Door

Everyone wants to live in a community until they actually do. The Laurel Canyon house was the epicenter of a movement, but it also highlighted the downside of "both sides" of fame. You want friends over, but you also want to be able to lock the door.

Joni’s home at 8217 Lookout Mountain Avenue is legendary. It’s where "Our House" by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young was written (about her and Graham Nash). It had two cats in the yard and life was used to be so hard. But houses like that are fragile. They represent a moment in time that can't be recreated by a developer or a clever interior designer.

- The Public Side: The parties, the jam sessions, the iconic photographs by Henry Diltz.

- The Private Side: The moments of profound doubt, the ending of relationships, and the transition from folk singer to jazz-inflected experimentalist.

Architecture as a Mirror of the Soul

When you look at the house both sides now through the lens of psychology, you realize our homes are just externalized versions of our brains. We have the "parlor" side that we show to guests—neat, curated, and slightly fake. Then we have the "basement" side—the storage units of our trauma, our unfinished projects, and the things we aren't ready to show the world.

✨ Don't miss: Why Washington University in St. Louis is the Most Misunderstood Elite School in America

Architectural critics often focus on the "flow" of a house. But Joni Mitchell’s homes never really flowed in a conventional way. They were layered. Her Bel Air home is filled with her own paintings. It’s a gallery as much as a residence. This is the ultimate "both sides" move: turning a domestic space into a professional one without losing the "hominess."

Honestly, most modern houses feel soul-less because they only have one side. They are built for resale value, not for living. They are "products." A true "both sides now" house is built for the person inhabiting it, with all their contradictions and weird habits.

The Cost of Living in a Masterpiece

Maintenance is the enemy of art. It’s the boring side of the house that no one writes songs about. Roof leaks, property taxes, and the general decay of materials. Even a genius like Mitchell had to deal with the mundane reality of owning property.

There’s a specific irony in owning a beautiful home and then spending all your time traveling to perform songs about how much you miss home. This is the central tension in "Both Sides, Now"—the idea that once you achieve the thing you thought you wanted (the house, the fame, the "win"), you realize you’ve lost the simplicity of the "losing" side.

Actionable Insights for Your Own Space

You don't need a Bel Air zip code to apply this logic to your life. Understanding the "both sides" of your own living situation is about intentionality.

1. Identify your "Quiet Side." Every house needs a zone that is strictly non-productive. No laptops. No phones. Just a chair and a view. This is your version of Joni’s Canadian retreat. If your whole house is "loud," you’ll burn out.

2. Embrace the "Rough Side." Don't fix everything. A house with zero flaws is a house without character. Joni liked the "wonky" aspects of her homes. Keep the creaky floorboard that lets you know someone is coming. Keep the wall where you accidentally spilled paint. It’s part of the narrative.

3. Curate your "Public Side" with honesty. When people enter your home, what do they see? If it’s just stuff you bought at a big-box store because it was on sale, you aren't telling your story. Put your "paintings" on the wall—even if your "painting" is just a collection of weird rocks or old concert tickets.

4. Understand the Seasonality of Space. Just as Joni’s music shifted from folk to jazz to pop, your house should change with you. Don't feel married to a layout just because that’s how it was when you moved in. If you need a studio more than a dining room, get rid of the table.

5. Look at the "Both Sides" of your Neighborhood. A house doesn't exist in a vacuum. It’s part of a street, a city, an ecosystem. Being a good neighbor is the "other side" of being a homeowner.

The house both sides now isn't a specific architectural style. It’s a philosophy of living where you accept that your home is both a sanctuary and a burden, a masterpiece and a work in progress. It’s about looking at your four walls and realizing that they are just a backdrop for the complicated, beautiful, and often contradictory life you’re living inside them.

Stop trying to make your house perfect for a magazine. Start making it perfect for the person you are when no one is looking. That’s the only way to truly see it from both sides.