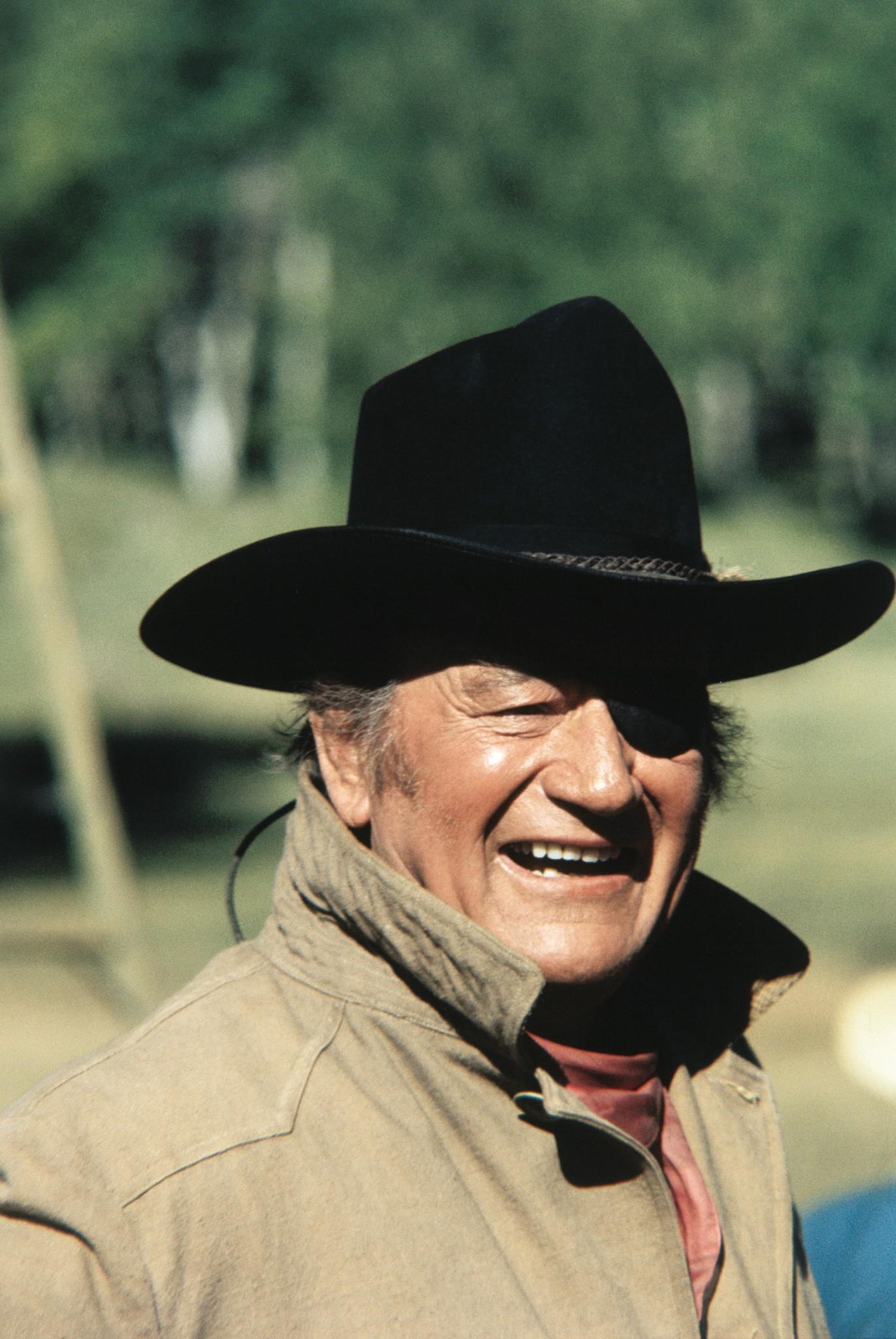

John Wayne was dying, and everyone in Hollywood knew it. By 1969, the man who basically invented the American cinematic cowboy was missing a lung and several ribs thanks to a 1964 bout with cancer. He was wheezing. He was sixty-two. He was, by all accounts, a relic of a past era. Then came John Wayne True Grit, a film that didn't just save his career—it defined his ghost.

People often forget that the Duke wasn't the first choice for Rooster Cogburn. He wasn't even the second. But the moment he put on that eyepatch, something clicked. It wasn't just another Western. It was a weird, poetic, almost Shakespearean take on the frontier that felt entirely different from the gritty "Spaghetti Westerns" Clint Eastwood was making popular at the time.

If you watch it today, you'll notice the dialogue is strange. It’s formal. Nobody uses contractions. "I shall not" instead of "I won't." That came straight from the Charles Portis novel, and it’s arguably the reason the movie works. It creates this elevated, mythic atmosphere that makes a fat, aging U.S. Marshal feel like a king in exile.

The Rooster Cogburn Reality Check

Most folks think Rooster Cogburn is just John Wayne playing John Wayne. That’s wrong. Honestly, it’s the opposite. For decades, Wayne played the stoic, invincible hero. In John Wayne True Grit, he played a "fat old man" who falls off his horse because he’s too drunk to stay in the saddle. He was mocking his own image.

The character is a mess. He’s a Marshal who lives in the back of a Chinese grocery store with a cat named General Sterling Price. He’s mean. He’s trigger-happy. He’s basically a mercenary with a badge.

Henry Hathaway, the director, was a notorious tyrant on set. He and Wayne had worked together before, but the tension on this shoot was palpable because Hathaway wanted to push Wayne away from his usual mannerisms. He wanted the grit. He got it. When you see Cogburn facing down the Lucky Ned Pepper gang at the end—reins in his teeth, Winchester in one hand, Colt in the other—that’s not just a stunt. That’s a man who knew this was his last chance to prove he was the greatest movie star on the planet.

Why the 1969 Version Outshines the Remake (Usually)

Look, the Coen Brothers’ 2010 version is technically a "better" film in terms of cinematography and historical accuracy. Jeff Bridges is great. But it lacks the meta-context that makes John Wayne True Grit essential viewing.

When you watch the 1969 version, you’re watching a passing of the torch. Kim Darby, who played Mattie Ross, was twenty-one at the time, playing fourteen. She and Wayne didn't get along. She thought he was an old-fashioned reactionary; he thought she was a "hippie" who couldn't act. That friction? It’s all over the screen. It makes their relationship feel genuinely uneasy, which fits the story perfectly.

📖 Related: Why Salt-N-Pepa Hot Cool & Vicious Is Actually the Most Important Debut in Hip-Hop History

Then you have Robert Duvall as Lucky Ned Pepper. Duvall was part of the "New Hollywood" wave. He was a Method actor. Watching him go toe-to-toe with the old-school Wayne is like watching two different philosophies of acting collide.

- The 1969 film used the bright, vivid colors of the San Juan Mountains in Colorado.

- The 2010 version was muted, brown, and bleak.

- Wayne’s performance earned him his only Oscar, a "legacy award" perhaps, but one he earned through sheer willpower.

The Oscar Controversy and the "Legacy" Win

Did John Wayne deserve the Academy Award for John Wayne True Grit? It’s a debate that still rages in cinephile circles. He was up against Richard Burton in Anne of the Thousand Days and Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy. In terms of "pure" acting, Hoffman probably had him beat.

But the Oscars aren't just about the performance in a vacuum. They’re about the narrative. Hollywood was changing fast in '69. Easy Rider had just come out. The studio system was collapsing. Giving Wayne the Oscar was the industry’s way of saying "thank you" to the man who built the house they were all living in.

When he walked onto that stage, he whispered to presenter Elizabeth Taylor, "Beginner's luck." He knew the score. He knew he was playing a caricature of himself, but he did it with such soul that you couldn't look away.

Behind the Scenes: The Stuff You Don't See

The filming wasn't easy. They were at high altitude, which is a nightmare when you only have one lung. Wayne had to carry an oxygen tank between takes. He was in constant pain.

There’s a specific scene where Rooster and Mattie are talking about his past—his wife who left him because he wouldn't settle down. Wayne plays it with this quiet, understated sadness that he almost never showed in his earlier films like The Searchers or Stagecoach. It’s a moment of vulnerability that feels remarkably human.

The casting of Glen Campbell as La Boeuf was a pure marketing move. He was a massive country star, and the producers wanted to draw in the younger crowd. He’s... okay. He’s not an actor, and it shows. But his presence adds to the "Hollywood Spectacular" feel of the movie. It’s a strange mix of high art and blatant commercialism that somehow just works.

What Most People Miss About the Ending

The ending of John Wayne True Grit is actually quite bittersweet, though the movie dresses it up in a heroic score by Elmer Bernstein. Rooster has saved the girl, but he’s still a lonely old man with no real future.

👉 See also: Why LEGO Rebuild the Galaxy is Actually the Weirdest Star Wars Story Ever Made

In the novel, Mattie grows up to be a spinster who loses her arm to gangrene and never sees Rooster again. The movie softens this. It gives them a final goodbye where Rooster jumps his horse over a fence just to show off. It’s a moment of pure cinematic joy. It’s Wayne saying, "I’m still here."

Key Takeaways for Your Next Rewatch

If you’re going back to watch this classic, pay attention to these specific elements that make it a masterpiece of the genre:

- The Dialogue Rhythm: Listen to how the characters speak. The lack of contractions makes every sentence feel like it’s carved in stone.

- The Landscape: They filmed in Ouray, Colorado. The scenery is a character itself, representing a frontier that is beautiful but indifferent to human life.

- The Eyes: Watch Wayne’s one good eye. He does more acting with that single eye than most actors do with their whole bodies.

Actionable Insights for Fans

If you want to truly appreciate the legacy of this film, don't just stop at the movie.

- Read the book by Charles Portis. It is arguably one of the greatest American novels of the 20th century. It’s funny, dark, and much weirder than the movie.

- Visit Ouray, Colorado. You can still see many of the filming locations, including the building used as the courthouse. It’s a pilgrimage every Western fan should make.

- Compare the shootout. Watch the final shootout in the 1969 version and then the 2010 version. Notice how the 1969 version emphasizes the "legend" while the 2010 version emphasizes the "chaos."

John Wayne True Grit isn't just a movie about a man with a badge and a girl with a grudge. It’s a film about the end of an era. It was the last time a classic Hollywood star could carry a film on the strength of his personality alone. It’s messy, it’s loud, and it’s occasionally cheesy—but it’s also undeniably great. It’s the Duke at his most honest.