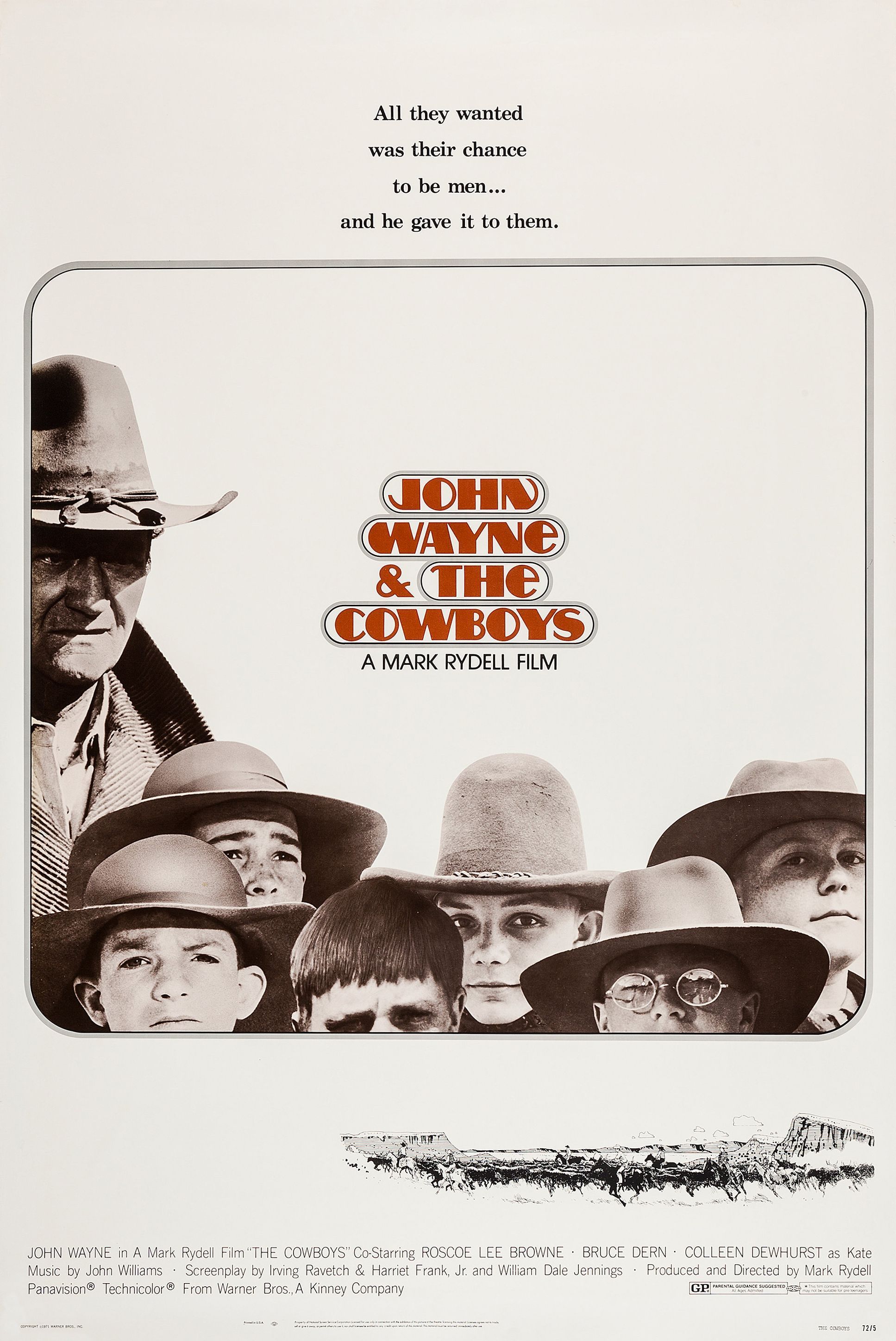

John Wayne was 64 years old when he sat on a horse in Durango, Mexico, and agreed to be murdered. He didn't just agree to it; he practically insisted on it. For a man whose entire screen persona was built on being the unbreakable pillar of American grit, dying on screen was a rarity. Dying at the hands of a "toothy, weasel-like varmint" played by Bruce Dern? That was unheard of.

But that's the magic of John Wayne and The Cowboys.

It isn't just another Western where the hero rides into the sunset. Honestly, it’s one of the most brutal and beautiful deconstructions of the American myth ever put to film. Most people remember it as "that movie where the kids go on a cattle drive," but it's actually much darker than that. It’s a story about the messy, violent transition from childhood to whatever comes next.

The Movie That Broke the Duke's Rules

By 1972, John Wayne was an institution. He’d won his Oscar for True Grit and was mostly playing variations of himself. Then comes Mark Rydell—a "liberal Jewish kid from the Bronx," as he described himself—who wanted to direct a story about an aging rancher, Wil Andersen, whose hired hands desert him for a gold rush.

Left with 1,500 head of cattle and a 400-mile deadline to Belle Fourche, South Dakota, Andersen does the unthinkable. He goes to the local schoolhouse.

He hires eleven boys. Some of them aren't even teenagers yet.

The studio wanted George C. Scott. Rydell wanted someone with weight. Wayne wanted the role because it reminded him of Goodbye, Mr. Chips and Sands of Iwo Jima. He saw the pattern: an older man takes a group of boys and initiates them into manhood by teaching them the "right" skills. But The Cowboys took that formula and shoved it into a meat grinder.

Why John Wayne and The Cowboys Is More Than a Western

When you watch the movie today, the first thing that hits you is the pacing. It starts almost like a Disney adventure. There’s a "thrilling audition" where Andersen makes the kids ride a bucking mare to the count of ten. You see the boys struggling with the reality of "butting heads" to settle differences. Wayne is gruff, sure, but there’s a genuine warmth there that felt different from his usual bravado.

✨ Don't miss: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

Then the tone shifts.

The introduction of Jebediah Nightlinger, played by the incredible Roscoe Lee Browne, adds a layer of complexity most Westerns of the era lacked. Nightlinger is the camp cook, a Black man in 1870s Montana who is smarter and more sophisticated than almost anyone else on the trail. His relationship with Wayne’s character is built on a mutual, silent respect for competence.

But then there’s the villain.

Bruce Dern: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance's Successor

Bruce Dern played Asa Watts, aka "Long Hair." He wasn't a "cool" outlaw. He was a psychopath. In one of the most chilling scenes in film history, Watts terrorizes a young boy named Dan (played by Nicolas Beauvy) who has a stutter, nearly drowning him in a river to prove a point.

The tension builds until the moment everyone remembers: the death of Wil Andersen.

Wayne actually told Dern to "kick his ass" in front of the kids during filming so they would be genuinely terrified of him. It worked. When Watts shoots an unarmed Andersen in the back, it’s a physical shock to the system. I’ve seen this movie with people who haven't seen it before, and they always gasp. It was the only time an audience ever gasped at a character Bruce Dern played, or so he claimed later.

After the movie came out, Dern couldn't walk into a bar for years without someone wanting to fight him for killing The Duke.

🔗 Read more: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The Controversy of the "Violent Rite of Passage"

Once Wayne is out of the picture, the movie takes a sharp turn into Lord of the Flies territory, but with better aim. Nightlinger helps the boys organize. They don't just go get their cattle back. They go on a calculated, lethal mission of revenge.

This is where the critics lost their minds in 1972.

- The Criticism: Many reviewers felt the film suggested that violence is the only way to become a man.

- The Reality: If you watch closely, Andersen actually spends the first half of the movie taking away the boys' guns and knives. He tries to teach them teamwork and discipline.

- The Outcome: The violence isn't a "choice" the boys make for fun; it’s a response to a world that took their father figure away.

The boys end the movie by selling the cattle in Belle Fourche. They take the money and pay a stonemason to carve a marker for Andersen’s grave. It doesn't say "Rancher" or "Boss." It says "Husband and Father."

That’s the heart of the film. It’s about the family you choose when the world gets cruel.

Behind the Scenes: Real Grit on the Set

The "cowboys" themselves were a mix of child actors and actual junior rodeo champions. Robert Carradine made his debut here. A Martinez played the brooding, older Cimarron. Then you had kids like Clay O'Brien, who was so small Wayne initially didn't want him.

Legend has it that O'Brien told Wayne, "I can drop you, you big son of a bitch," and then proceeded to rope and drop the biggest movie star in the world onto his backside. Wayne hired him on the spot. O'Brien went on to win seven World Champion rodeo titles in real life.

Filming took place across the Southwest:

💡 You might also like: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

- Bonanza Creek Ranch: Just outside Santa Fe, New Mexico.

- J.W. Eaves Movie Ranch: Another iconic New Mexico spot.

- Castle Rock, Colorado: Used for some of the sweeping trail shots.

The boys spent eight weeks in intense riding training before the cameras even rolled. Half the kids taught the actors how to ride, and the actors taught the rodeo kids how to deliver a line.

How to Revisit the Legend

If you’re looking to dive back into the world of John Wayne and The Cowboys, you shouldn't just watch the movie. You need to look at the legacy.

First, track down the 50th-anniversary panels. Several of the original "boys"—now men in their 60s and 70s—still get together to talk about the shoot. Robert Carradine and A Martinez have done some great interviews lately about how emotional it was to film Wayne’s death scene. For them, it wasn't just acting; they had spent months looking up to this man as a mentor.

Second, if you’re ever in Fort Worth, go to the "John Wayne: An American Experience" exhibit. They have artifacts from the film and a deep dive into the making of the cattle drive.

Finally, watch the movie again, but ignore the "Western" tropes. Look at it as a coming-of-age drama. Notice the score by a young John Williams—yes, the Star Wars and Jaws John Williams. It’s one of his most underrated works, full of sweeping Americana that makes the final act feel even more tragic.

Practical Next Steps for Fans:

- Check the Credits: Watch for Richard Farnsworth. He’s an uncredited stuntman in this movie who eventually became a massive star in his own right.

- Compare the Book: Read the 1971 novel by William Dale Jennings. It’s even grittier than the film and gives more back-story on Asa Watts’ gang.

- Location Scout: Plan a trip to the Bonanza Creek Ranch in New Mexico if you want to stand where the Duke stood. Many of these ranches still offer tours to film buffs.

There’s a reason people still talk about this film while other Wayne movies have faded. It dared to show the hero failing, so that the next generation could find their own way. It’s messy, it’s violent, and it’s arguably the most honest movie John Wayne ever made.