You’ve probably seen the clip. A young, afro-sporting Jesse Jackson stands on the steps of Sesame Street in 1972, surrounded by a sea of kids from every background imaginable. He leans in, his voice cracking with a rhythmic, preacher-like intensity, and leads them in a chant that would eventually echo through the halls of the US Capitol and across international borders. "I am—" he shouts. "Somebody!" the kids roar back.

It feels like a simple moment of 70s nostalgia, but Jesse Jackson I Am Somebody was never just a feel-good nursery rhyme.

Honestly, it was a psychological survival tactic. In a world that was systematically telling Black and brown children they were "less than," Jackson was performing a kind of public soul-surgery. He was trying to graft dignity onto a generation that the "system" had largely written off.

The Surprise History: It Wasn't Just Jackson

Most people think Jesse Jackson wrote the poem. He didn't.

The roots actually go back to the 1940s and 1950s. The original "I Am Somebody" was composed by Reverend William Holmes Borders Sr., a legendary pastor at Atlanta’s Wheat Street Baptist Church. Borders was a giant of the early civil rights movement—a mentor to Martin Luther King Jr. himself. His version was a sprawling, epic "Negro History" poem that listed the achievements of Black scientists, athletes, and thinkers. It was a litany of proof that Black people had already contributed the world.

Jackson took that foundation and stripped it down. He made it lean. He turned it into a "litany" for the streets. While Borders focused on the greatness of the past, Jackson focused on the inherent worth of the person standing in the room right now—even if that person was broke, unemployed, or "on welfare."

Why "I Am Somebody" Became a Political Weapon

By 1971, Jackson was at a crossroads. He had been a close aide to Dr. King, but after the assassination in Memphis, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was fracturing. Jackson wanted to focus on "civil economics." He believed that for Black Americans to be truly free, they needed more than just the right to vote; they needed the right to a bank loan and a decent job.

He founded Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) in Chicago. The chant became the organization's heartbeat.

🔗 Read more: Judge Burton C. Conner Democrat or Republican: What Most People Get Wrong

It wasn't just words; it was a brand for a new movement:

- The 1971 Black Expo: Jackson used the mantra to organize Black-owned businesses, proving they could sustain their own economy.

- The Wattstax Festival (1972): Standing before 100,000 people at the Los Angeles Coliseum, Jackson delivered the "I Am Somebody" speech in what many call the "Black Woodstock." It was a moment of peak cultural power.

- The 1984 & 1988 Presidential Runs: By the time Jackson ran for President, the phrase had morphed into a political platform. It was the "Rainbow Coalition" in three words.

The genius of the phrase is its flexibility. It works for a five-year-old on a puppet show and for a factory worker on strike. It basically says that your value is "divine" and "inherent," not something granted by a boss or a government.

The Critics and the Controversy

Not everyone loved it. Some critics at the time—and even today—argued that Jackson’s focus on "somebodyness" was a bit too much about self-esteem and not enough about structural change. They thought it was "soft."

But if you look at the actual text Jackson used at events like Wattstax, it’s anything but soft. He would say, "I may be poor, but I am somebody. I may be on welfare, but I am somebody." He was explicitly calling out the economic conditions of the time. He was demanding that the "unskilled" and the "marginalized" be "respected, protected, and never rejected."

👉 See also: No Taxes on Tips Act: What the News Isn't Telling You About Your Take-Home Pay

Why We Are Still Talking About This in 2026

You might wonder why a 50-year-old chant still pops up in Super Bowl commercials and viral TikToks.

It’s because the "identity crisis" Jackson was addressing hasn't gone away. Whether it’s the struggle for voting rights or the fight for economic equity in the age of AI, the core question remains: Do I matter in this system?

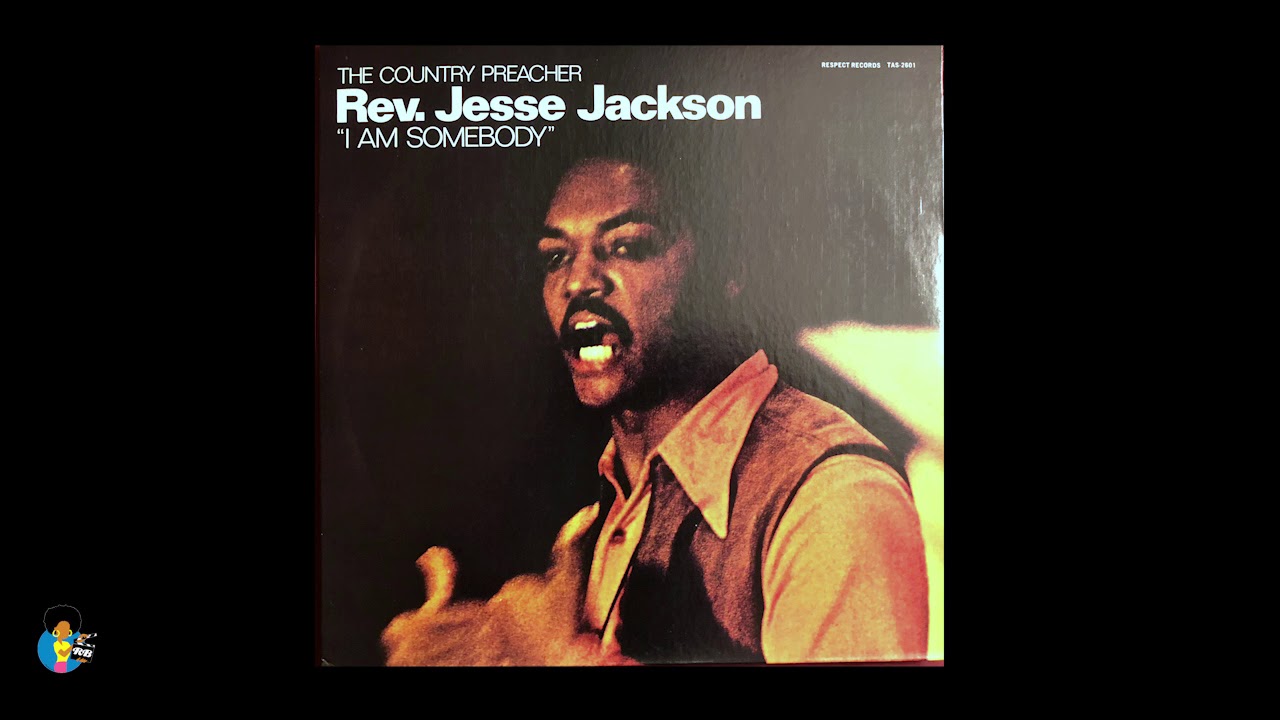

Jackson’s legacy is often debated—his ambition, his flair for the dramatic, his "Country Preacher" persona. But you can't argue with the results. He helped bridge the gap between the protest era of the 60s and the political representation we see today. Without the "I Am Somebody" movement, it's hard to imagine the path for figures like Barack Obama or the modern push for corporate diversity.

💡 You might also like: Is Trump Sending the National Guard to Chicago? What Really Happened

How to Apply the "I Am Somebody" Mindset Today

If you want to take something actionable from this history, it’s not just about reciting a poem. It’s about the "Civil Economics" Jackson preached.

- Support Local/Minority Businesses: This was the "Operation PUSH" model. Use your "somebodyness" with your wallet.

- Advocate for Self-Respect in Education: Jackson’s PUSH-Excel program was about pushing students to excel despite their circumstances. It’s a call to take ownership of your learning.

- Find Your Litany: Everyone needs a mantra that reminds them of their baseline worth when the world gets noisy.

Jesse Jackson is 84 now, and he’s stepped back from the front lines, but that chant is bigger than the man. It’s a permanent part of the American psyche. It reminds us that dignity isn't a gift—it's a birthright.

To really understand the power of this moment, look up the original footage from the 1972 Wattstax performance. Listen to the crowd. You’ll hear more than just a chant; you’ll hear the sound of a community deciding to believe in itself.

Actionable Insight: Research the history of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition to see how economic advocacy evolved from these early chants into actual policy changes in corporate America. Understanding the "litany" is the first step; seeing the "legislation" is the second.