You’re standing on a slab of shale, your calves probably burning from the incline, looking out at where the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers crash into each other. It’s loud. It’s windy. It’s exactly what Thomas Jefferson saw in 1783, and honestly, the guy wasn’t exaggerating when he said the view was worth a voyage across the Atlantic. Most people visiting Harpers Ferry National Historical Park just follow the signs, take a quick selfie at Jefferson Rock, and head back down for fudge. They’re missing the point.

The view isn't just about "pretty mountains." It’s about a massive geological rupture.

Jefferson sat here on October 25, 1783. He was on his way to Philadelphia. He looked at the water gap—the place where the rivers basically sawed through the Blue Ridge Mountains—and saw a war between water and stone. He wrote about it in his Notes on the State of Virginia. He called it "stupendous." That's a big word for a guy who seen a lot of scenery. But when you’re standing there, you see the "Blue Ridge" isn't just a name; it’s a physical wall that got pulverized by the force of nature.

The Physics of a Precarious Landmark

Let’s talk about why the rock looks like it’s wearing a hat.

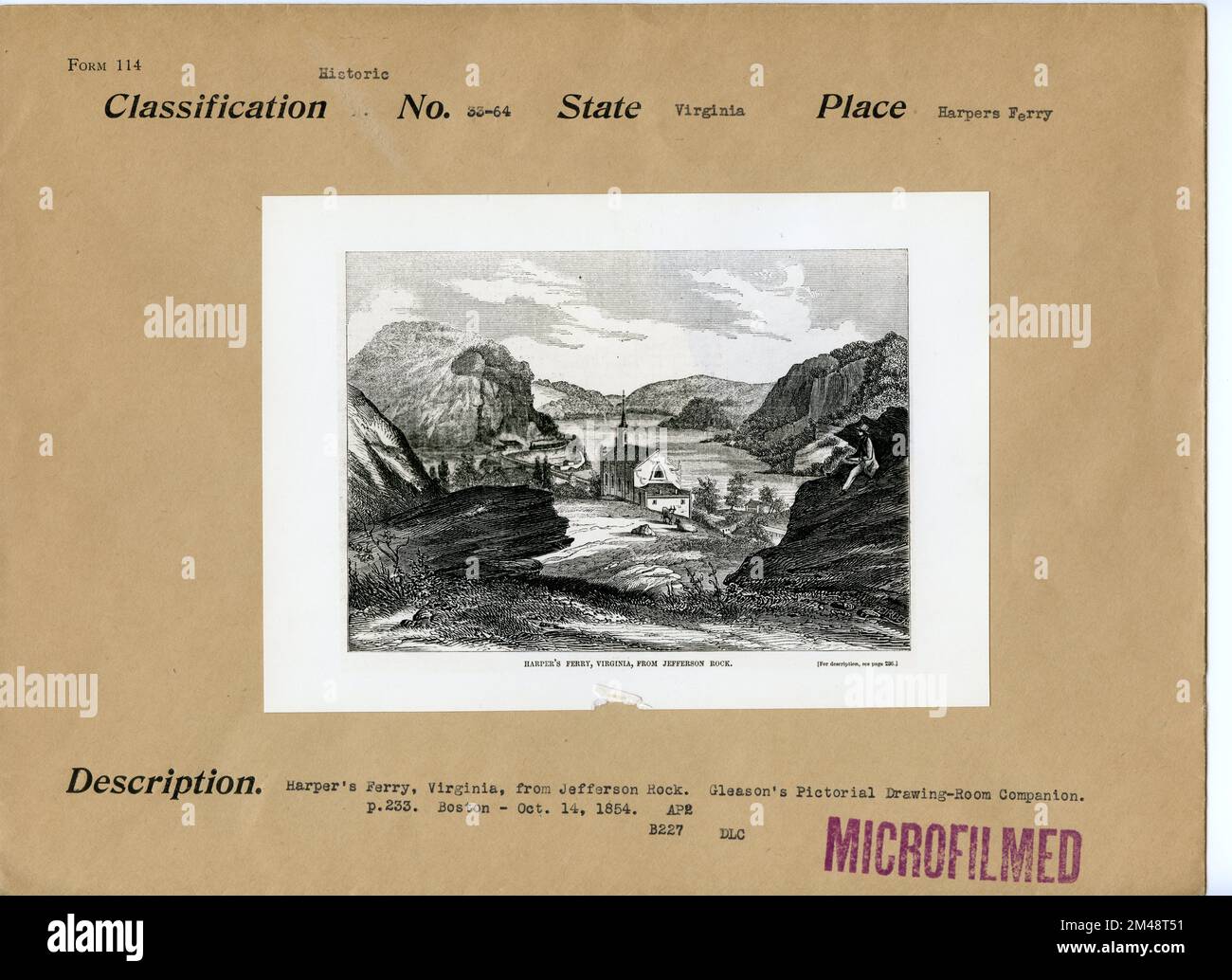

If you look at old sketches from the 1800s, Jefferson Rock looked way more terrifying than it does now. It was a series of massive, flat slabs balanced on a tiny, narrow base. It looked like a sneeze would knock it into the Lower Town. By the mid-19th century, it was actually becoming a hazard. People were literally rocking it. To keep the whole thing from tumbling down and crushing a blacksmith shop or a house, four stone pillars were placed under the uppermost slab between 1855 and 1860.

It’s a bit of a cheat, sure.

🔗 Read more: El Cristo de la Habana: Why This Giant Statue is More Than Just a Cuban Landmark

Without those red sandstone supports, the landmark probably wouldn't exist today. Erosion is a beast. The Appalachian Trail passes right by here—literally, the white blazes lead you right past the rock—and thousands of boots every year add to the wear and tear. The rock itself is Harpers Shale. It’s flaky. It’s layered. It’s not granite. It’s fragile, which is why there are signs everywhere begging you not to climb on it. Seriously, don’t be that person. The rock is essentially a geological fossil of a moment in time when the Earth’s crust was folding like a piece of laundry.

Getting There Without Losing Your Mind

The hike to Jefferson Rock is short but deceptively steep if you aren't used to stairs.

Start at the Lower Town. You’ll see the stone steps carved into the hillside next to St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church. Those steps are an experience by themselves. They’re uneven. They’re old. They feel like something out of a European village. Once you pass the church and the ruins of St. John’s Episcopal Church, the path levels out onto the Appalachian Trail.

- Distance: It’s barely half a mile from the center of town.

- Difficulty: Moderate—mostly because of the vertical gain in the first five minutes.

- The Vibe: Historical haunting mixed with fresh mountain air.

If you go in the middle of a Saturday in July, you’ll be sharing the view with fifty other people and at least three dogs. If you go at 7:00 AM on a Tuesday? You’ll have the "stupendous" view all to yourself. The mist rolls off the Shenandoah River and gets trapped in the gap. It looks like the world is still being created.

Why Jefferson Actually Cared

Jefferson wasn't just a tourist; he was a nerd for natural philosophy. When he described this spot, he wasn't looking for a postcard. He was trying to prove that American nature was just as grand, if not grander, than Europe’s. At the time, Buffon—a famous French naturalist—was claiming that everything in the New World was shriveled and inferior. Jefferson used Jefferson Rock and the surrounding Blue Ridge as Exhibit A for his rebuttal.

💡 You might also like: Doylestown things to do that aren't just the Mercer Museum

He saw the gap as a "rupture." He imagined the ocean once dammed up behind these mountains, finally bursting through in a cataclysmic flood. Modern geology tells us it was a bit slower than that—the rivers cut down as the mountains rose up—but the visual drama remains the same.

The Blue Ridge is ancient. We’re talking over a billion years for some of the basement rock. The shale you’re standing on at the rock is younger, but it’s seen the rise and fall of several mountain chains. It’s seen the Civil War smoke rise from the valley below. It saw John Brown’s raid. It saw the floods of 1889, 1924, and 1936 that nearly erased Harpers Ferry from the map.

Common Misconceptions About the Spot

- Jefferson signed the Declaration here. No. Not even close. He was just passing through.

- The rock is solid stone. Nope, it’s a stack. If you look closely at the "legs," you can see the masonry work from the 1850s.

- It’s the highest point in town. It feels like it, but Bolivar Heights and Maryland Heights both tower over it. However, it definitely has the best "framing" for a photo.

The Appalachian Trail Connection

You can’t talk about Jefferson Rock without mentioning the "AT." This stretch of trail is part of the "psychological halfway point" for thru-hikers walking from Georgia to Maine. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy headquarters is just a few blocks away. When you’re at the rock, you’ll often see hikers with massive packs, looking a little scraggly and very hungry.

They’ve walked over 1,000 miles to get to this specific rock.

It puts your 15-minute walk from the parking lot into perspective. For them, this view is a milestone. It’s the transition from the relatively mellow Virginia ridges into the rocky, technical terrain of Maryland and Pennsylvania. There’s a weight to the air here that isn't just humidity. It’s history.

📖 Related: Deer Ridge Resort TN: Why Gatlinburg’s Best View Is Actually in Bent Creek

Survival Tips for Your Visit

Harpers Ferry is a weird place. It’s a National Park, but it’s also a living town.

Parking is a nightmare. Do not try to park in the Lower Town. You won't find a spot, and you'll just get frustrated. Park at the main Visitor Center off Highway 340 and take the shuttle bus. It’s free with your entrance fee and drops you right where the trail starts.

Bring water. Even though the walk to the rock is short, the humidity in the Potomac Valley is legendary. It’s like breathing through a warm, wet washcloth in August. Also, wear actual shoes. I see people trying to climb those stone stairs in flip-flops every summer, and it always ends with someone twisting an ankle on the shale.

If you want the full experience, don't stop at the rock. Keep walking past it. The trail continues up toward the Harper Cemetery. It’s quiet there. Robert Harper, the guy the town is named after, is buried there. From that vantage point, you can look down on the church and the rock and see how the whole town clings to the side of the mountain like a stubborn barnacle.

The Actionable Way to Experience Harpers Ferry

Don't just look at the rock.

- Read the Quote: Before you go, find the text of Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia. Read his description of the "passage of the Patowmac through the Blue Ridge." It changes how you see the horizon.

- Check the Light: The sun sets behind the mountains, so the "Golden Hour" here is actually a bit earlier than you’d think. Aim for about 90 minutes before official sunset to get the best light on the water.

- Extend the Loop: After hitting Jefferson Rock, follow the AT down to the footbridge across the Potomac. Walk across to the C&O Canal towpath. Look back up. Seeing the rock from below gives you a terrifying sense of how high up you actually were.

- Support the Park: Harpers Ferry is fragile. Stick to the marked trails. The shale cliffs are prone to rockslides, and the vegetation is easily trampled.

Jefferson Rock isn't just a pile of stone. It’s a witness. It’s been there through the birth of a nation, the carnage of the 1860s, and the slow rebirth of the wild Appalachians. Go stand where the President stood, feel the wind coming through the gap, and realize that some views really are worth a trip across an ocean. Or at least a drive from D.C.

To make the most of your trip, grab a physical map at the Visitor Center first—cell service is notoriously spotty in the shadows of the water gap, and you’ll want to know which trail leads to the overlook versus which one takes you halfway to Loudoun Heights.