Isaac Bashevis Singer didn’t just write stories. He trapped ghosts, demons, and the messy, sweating reality of a vanished world inside his pages. If you pick up one of the many Isaac Bashevis Singer books sitting on a library shelf today, you aren't just reading "literature" with a capital L. You’re stepping into a Polish shtetl or a cramped Upper West Side apartment where God is silent, but the devils are incredibly chatty.

It's weird.

Singer won the Nobel Prize in 1978, which usually means a writer is destined to become a dusty statue. But his work avoids that fate because it’s so stubbornly human. He wrote in Yiddish—a language that many felt was dying or already dead—yet he reached a global audience. Why? Because he knew that whether you’re in 19th-century Warsaw or 21st-century New York, people are basically the same: we’re driven by hunger, lust, doubt, and a desperate need to find meaning in a world that often looks like a cruel joke.

The Satan in Goray and the Fever of False Hope

Most people start their journey with Singer’s debut novel, Satan in Goray. It’s a slim book, but it packs a punch that leaves you reeling. Published in 1935, it looks back at the aftermath of the Chmielnicki massacres in the 17th century. Imagine a small town so broken by trauma that they'll believe anything to feel safe again.

Then comes the news of Sabbatai Zevi, the "false messiah." The town of Goray loses its mind. Singer describes the religious ecstasy turning into something grotesque. It’s a warning about extremism that feels almost too relevant in our current era of internet rabbit holes and cultish devotion. He doesn't judge the characters from a distance. He gets right in the mud with them. You feel the hysterical joy and the inevitable, crushing despair when the savior turns out to be a fraud.

Honestly, it’s a horror novel. Not the jump-scare kind, but the kind that sits in your stomach for a week.

Why His Short Stories Are the Real Magic

While his novels are massive, many critics—and I’d agree—argue his short stories are where the real lightning strikes. Have you read "Gimpel the Fool"?

If you haven’t, stop what you’re doing. It’s arguably one of the greatest short stories ever written in any language. Saul Bellow translated it into English, and that translation basically launched Singer’s career in America. Gimpel is a man who is lied to by everyone. His wife, his neighbors, the whole town treats him like a doormat. But Gimpel decides that it’s better to believe a lie than to live in a world of constant suspicion.

🔗 Read more: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

"No doubt the world is entirely an imaginary world," Gimpel says, "but it is only once removed from the true world."

That’s the core of the Isaac Bashevis Singer books experience. He balances on the edge of cynicism and deep, spiritual yearning. He knows people are liars, but he thinks there’s something holy about the attempt to believe anyway.

The Family Moskat and the Epic Scale of Loss

If you want the "big" experience, The Family Moskat is the one. It’s often compared to The Buddenbrooks or The Forsyte Saga. It’s a sprawling, multi-generational epic about a wealthy Jewish family in Warsaw.

But there’s a shadow hanging over every page.

Because we, the readers, know what’s coming in 1939, and the characters don't. Watching them argue about money, marriage, and Zionism while history is preparing to erase them is agonizing. Singer wrote this after moving to New York, and you can feel his survivor’s guilt bleeding through the prose. It’s not just a book; it’s a memorial built out of ink.

- Enemies, A Love Story: This one is dark. A Holocaust survivor in New York finds himself married to three different women at the same time. It sounds like a farce, but it’s actually a devastating look at trauma.

- The Slave: A beautiful, lyrical story set in the 17th century about a Jewish man enslaved by Polish peasants. It’s a love story that shouldn't work but somehow does.

- The Estate and The Manor: These are massive historical novels that track the modernization of Poland. They’re dense, sure, but they’re filled with such specific details about food, clothing, and smells that you feel like you’ve actually lived there.

The Supernatural Is Just Around the Corner

One thing that surprises new readers is how much Singer loves demons. Impish spirits, dybbuks, and fallen angels show up all the time. But here’s the thing: they aren’t metaphors. Not exactly.

To Singer, the supernatural was just another layer of reality. He once famously said that he believed in demons because he’d seen what humans are capable of—surely we can’t be doing all this evil on our own? In stories like "The Last Demon," he portrays a bored devil who has nothing left to do because the Nazis did a better job of destroying souls than he ever could. It’s chilling.

💡 You might also like: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

It’s this mix of the folkloric and the modern that makes his work so addictive. You’ll be reading a story about a philosopher in New York, and suddenly a spirit from a Polish village shows up. It’s a "kinda" magical realism before that term was even cool.

Sex, Sin, and the Nobel Prize

Let’s be real for a second: Singer was scandalous.

The traditional Yiddish literary establishment often hated him. They thought he was too obsessed with sex and the "ugly" side of Jewish life. They wanted "noble" characters who represented the community well. Singer gave them thieves, prostitutes, and neurotic intellectuals.

He didn't care about being a PR agent for his culture. He wanted to show the truth.

His characters are often driven by their "unclean" thoughts. In The Magician of Lublin, the protagonist, Yasha, is an acrobat and a womanizer who wants to fly—literally and figuratively. He’s caught between his desire for freedom and his fear of God. That tension is the engine that drives almost all Isaac Bashevis Singer books. We want to be good, but we’re so easily distracted by the flesh.

How to Start Reading Singer Without Feeling Overwhelmed

If you’re staring at a long list of titles, don’t panic. You don't have to read them in order.

- Start with The Collected Stories. It gives you the full range of his voice, from the mystical to the gritty.

- Move to Enemies, A Love Story. It’s his most accessible "modern" novel and has a fast, cinematic pace.

- Then dive into The Slave if you want something poetic, or Satan in Goray if you want something haunting.

- Save The Family Moskat for when you have a long weekend and a lot of coffee.

The Language Question: Why Yiddish Matters

Singer wrote in Yiddish until the day he died. He’d write his stories in notebooks, and then work closely with translators to bring them into English. He often called Yiddish the "language of the underdog," a tongue full of humor and "pious despair."

📖 Related: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

There’s a specific rhythm to his prose that survives the translation. It’s punchy. It’s rhythmic. He doesn't waste time with flowery descriptions of sunsets unless that sunset is going to make a character contemplate their own mortality. Every sentence has a job to do.

He lived in two worlds. He was a vegetarian who fed pigeons in New York City, but his mind was always wandering the streets of Krochmalna Street in Warsaw. That duality is why his books feel so unique. They are displaced. They belong to no single time or place, which makes them belong to everyone.

The Misconception of the "Grandfatherly" Storyteller

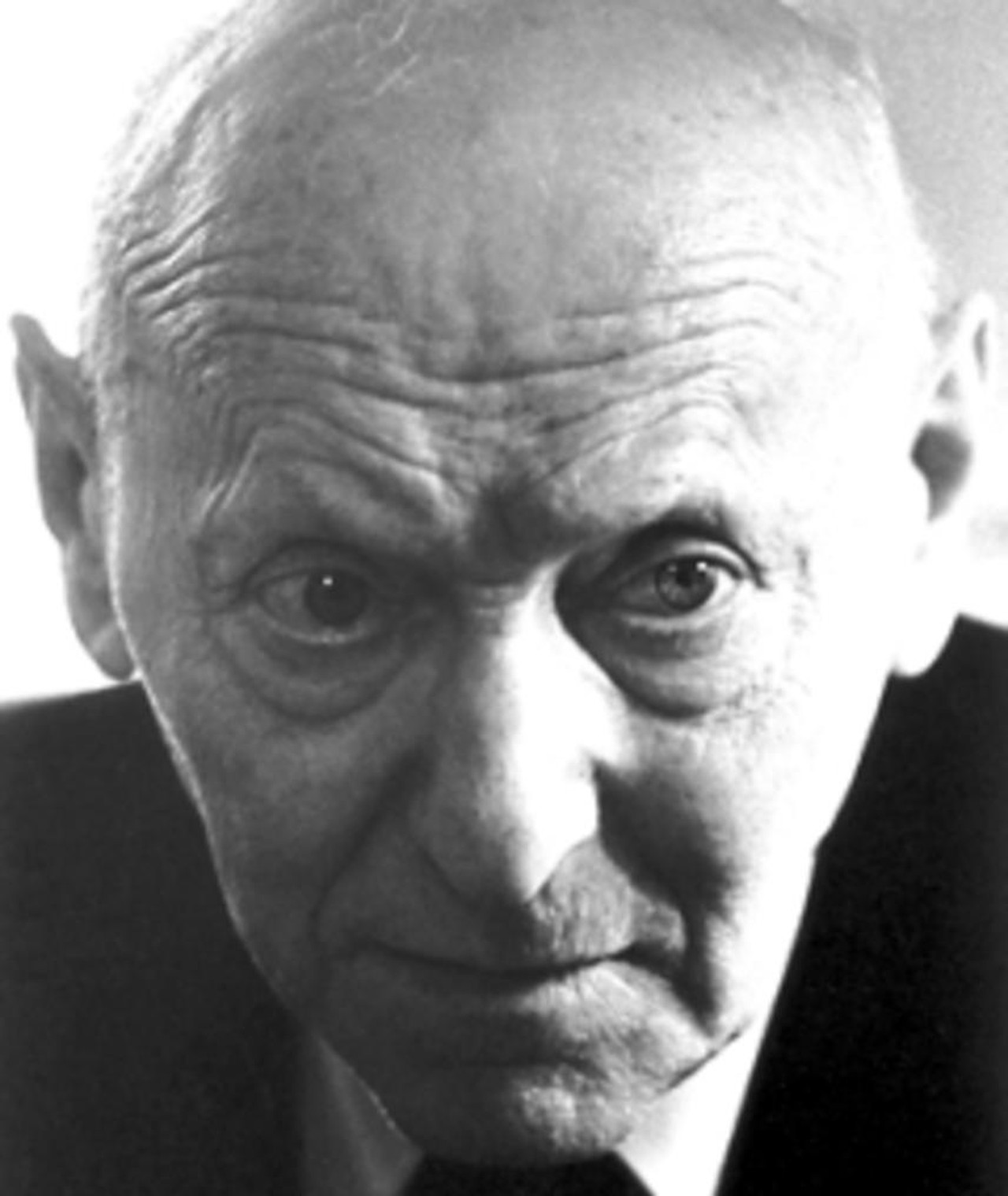

Because he lived to be an old man with a gentle face and a funny accent, people sometimes mistake him for a cute storyteller of "Old World" charms.

That’s a mistake.

Singer is fierce. He’s often cruel to his characters. He explores the depths of nihilism and the possibility that the universe is just a chaotic mess with no one at the wheel. If you’re looking for "fiddler on the roof" sentimentality, you won't find it here. You’ll find something much sharper and more dangerous.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you want to truly appreciate his work, keep these things in mind:

- Look for the contradictions. If a character seems holy, look for their vice. If they seem evil, look for their spark of kindness. Singer never wrote one-dimensional people.

- Pay attention to the animals. Singer was a passionate vegetarian and often wrote about the suffering of animals as a parallel to human suffering. This comes through strongly in stories like "The Slaughterer."

- Don't skip the introductions. Singer often wrote prefaces to his books that are as insightful as the stories themselves, explaining his philosophy on art and ghosts.

- Contextualize the "dying" language. Remember that when he was writing, he was often told he was writing for a graveyard. The vitality of his prose is a middle finger to that idea.

Isaac Bashevis Singer books remain essential because they refuse to simplify the human experience. They embrace the fact that we are contradictory, lustful, spiritual, and terrified beings.

To start your collection, look for the Library of America editions. They’ve done a stellar job of collecting his work in high-quality volumes that will last as long as the stories themselves. Pick one up, open to a random page, and let the demons of Warsaw start talking to you. You won't regret it.