It’s the question that pops up every time you scroll through a news feed or turn on a TV. You see a headline about a drone strike, a protest in a capital city you can't quite pronounce, or a sudden spike in oil prices, and you wonder: Why is the Middle East so unstable? Honestly, the answer isn't just "religion" or "ancient hatreds." That’s a lazy trope. If you actually look at the map, the history, and the way money moves through the region, you start to see a much messier, more human reality. It's a mix of bad borders drawn by bored Europeans, a literal ocean of oil, and a few powerful families playing a high-stakes game of chess with millions of lives.

It’s complicated. It’s frustrating. And if we’re being real, a lot of the instability was imported from the outside.

The Ghost of 1916: Borders That Make No Sense

You’ve probably heard of the Sykes-Picot Agreement. If you haven't, it’s basically the reason the map looks the way it does. Back in 1916, two guys named Mark Sykes (British) and François Georges-Picot (French) sat down with a ruler and literally drew lines across a map of the crumbling Ottoman Empire.

They didn't care about who lived where. They didn't ask the Kurds if they wanted to be split between four different countries. They didn't care that they were putting Sunni and Shia populations—who had their own distinct political histories—into the same "nation" and telling them to just figure it out.

When you force different ethnic and religious groups into a single cage and tell them to compete for resources, you don't get a democracy. You get a power struggle. Iraq is the poster child for this. You have a Shia majority, a large Sunni minority, and a massive Kurdish population in the north. For decades, it only "stayed together" because a dictator like Saddam Hussein used extreme violence to keep the lid on. When the lid was blown off in 2003, everything boiled over.

Bad borders aren't just a historical footnote. They are a daily reality. Think about Lebanon. It’s a tiny country where the entire government is structured around a delicate religious balance—the President must be a Maronite Christian, the Prime Minister a Sunni Muslim, and the Speaker of the Parliament a Shia Muslim. It sounds organized on paper, but in reality, it creates a stagnant system where nothing gets done because everyone is afraid of losing their slice of the pie.

The "Resource Curse" and the Fight for the Tap

Money changes everything. In the Middle East, that money is oil.

Economists call it the Resource Curse. Basically, if a government gets all its money from selling oil to foreigners rather than taxing its own citizens, it doesn't actually have to listen to its people. Why would it? If you don't pay taxes, the government doesn't owe you a voice. This is why many oil-rich states are authoritarian. They can just buy off the population with subsidies or crush them with a well-funded police force.

✨ Don't miss: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

Then there’s the regional rivalry. Think of Saudi Arabia and Iran.

They are the two big kids on the playground, and they hate each other. It’s not just about the Sunni-Shia divide, though that’s a convenient way to drum up support. It’s about who gets to be the boss of the neighborhood. They don't fight directly—that would be too expensive and dangerous. Instead, they fight "proxy wars."

- In Yemen, the Saudis support the government while Iran supports the Houthi rebels.

- In Syria, Iran backs the Assad regime while Saudi Arabia (and others) backed various rebel groups.

- In Lebanon, Iran funds Hezbollah, creating a state-within-a-state that drives the Saudis crazy.

This constant tug-of-war makes it impossible for smaller countries to find their footing. Every time a local conflict starts, a regional power dumps money and guns into it to make sure their side wins. It turns local grievances into international catastrophes.

Why is the Middle East so unstable? Look at the "Youth Bulge"

Here is a statistic that doesn't get enough play: roughly 60% of the population in the Middle East is under the age of 30.

That is a lot of energy. In a healthy economy, that’s a "demographic dividend"—tons of young workers driving growth. But in the Middle East, the economies are often stuck. Corruption is rampant. To get a government job in Cairo or Baghdad, you often need "wasta" (connections), not just a degree.

When you have millions of young people who are educated but unemployed, you have a recipe for revolution. We saw this in 2011 with the Arab Spring. People were tired of dignity being a luxury they couldn't afford. But when those protests failed to bring quick change—or when they were met with bullets—the vacuum was filled by extremists.

Groups like ISIS didn't appear out of thin air. They recruited from the disillusioned. They offered a sense of purpose and a paycheck to people who had neither. If you want to know why the region feels like a tinderbox, look at the unemployment rates for 20-somethings in Tunisia, Jordan, or Egypt. It's terrifying.

🔗 Read more: Percentage of Women That Voted for Trump: What Really Happened

The Intervention Problem

We can't talk about instability without talking about the West. The United States, Russia, and former colonial powers like Britain and France have a long history of "helping" in ways that backfire spectacularly.

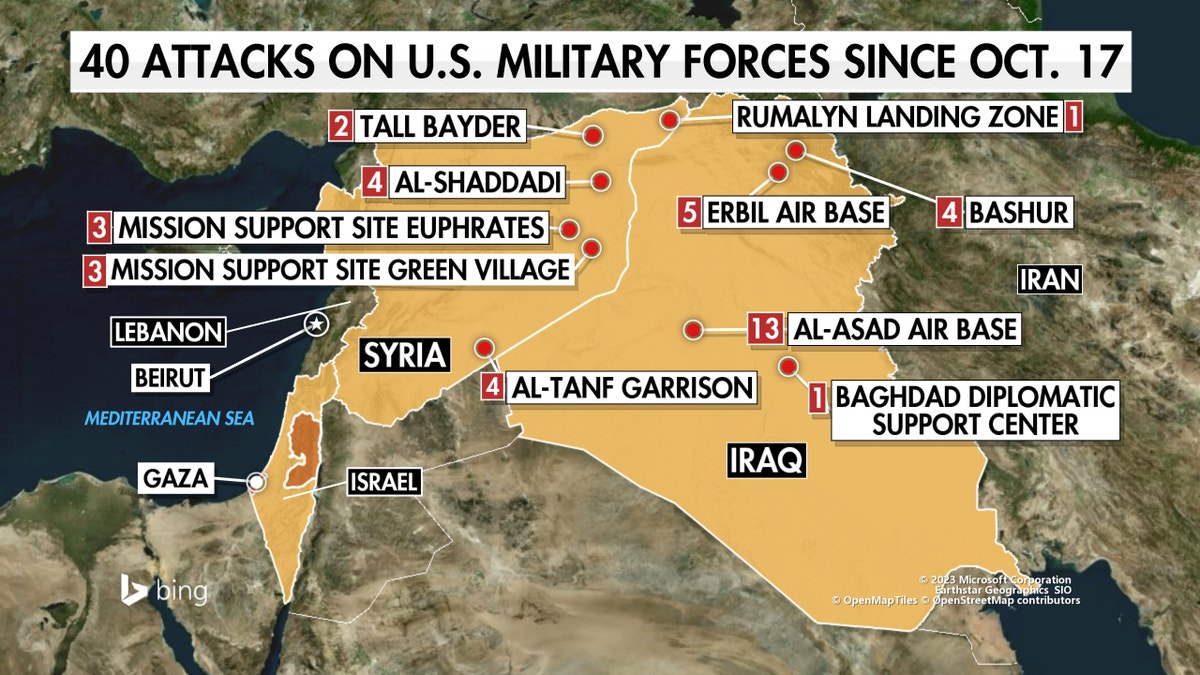

The 2003 invasion of Iraq is the most obvious example. It dismantled the existing state structure without a viable plan for what came next. The resulting vacuum birthed Al-Qaeda in Iraq, which eventually became ISIS. But it goes back further. The 1953 coup in Iran—orchestrated by the CIA and MI6 to keep the oil flowing—toppled a democratically elected leader and paved the way for the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Every time an outside power steps in to "stabilize" the region for their own strategic interests, they usually end up knocking over a different set of dominoes. Whether it's the Cold War maneuvering of the 1970s or the modern-day drone campaigns, foreign intervention often provides a short-term fix while creating long-term resentment.

Water: The Next Great Conflict

While everyone is watching the oil prices, the real crisis might be the tap. The Middle East is one of the most water-stressed regions on the planet.

Look at the Nile. Ethiopia is building a massive dam (the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam), and Egypt is rightfully panicked that it will cut off their primary water source. Look at the Tigris and Euphrates. Turkey builds dams upstream, and suddenly Iraq and Syria are drying up.

Climate change is making this worse. Rapidly. When farms dry up, farmers move to the cities. When cities get overcrowded and can't provide services, people get angry. When people get angry, governments get nervous and start cracking down. It's a cycle that leads right back to that word: instability.

Breaking Down the Misconceptions

People love to say the Middle East has been "fighting for thousands of years."

💡 You might also like: What Category Was Harvey? The Surprising Truth Behind the Number

That's just factually wrong. During the Golden Age of Islam, while Europe was in the Dark Ages, Baghdad was the intellectual center of the world. Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived and worked together in places like Al-Andalus and the Ottoman Empire for centuries.

The current "instability" is largely a modern phenomenon. It’s a product of the 20th century—the collapse of empires, the discovery of oil, and the Cold War. It's not an ancient curse. It's a series of political and economic failures.

Real-World Impacts You Can See Today

- Refugee Crises: The war in Syria alone forced over 6 million people to flee the country. This didn't just hurt Syria; it strained the resources of Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, and even shifted the politics of the European Union.

- Global Shipping: Think about the Red Sea. When the Houthis start firing at cargo ships, global supply chains stutter. Your Amazon package gets delayed, and gas prices in Ohio go up.

- Extremism: Instability creates "ungoverned spaces." When a government loses control of its territory, groups like Al-Qaeda move in. This makes the region a playground for global terror networks that export violence far beyond the Middle East.

What Needs to Change? (Actionable Insights)

So, is the region doomed to be a war zone forever? Not necessarily. But the "solutions" usually offered by outsiders aren't working. Here is what actually matters for long-term stability:

- Economic Diversification: Countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia (through Vision 2030) are trying to move away from oil. If they can create real jobs in tech, tourism, and manufacturing, they can lower the temperature of the "youth bulge."

- Regional Diplomacy: The recent "thaw" between Saudi Arabia and Iran (brokered by China) is a huge deal. If the two big powers stop using other countries as battlegrounds, local conflicts have a chance to actually settle.

- Water Management: There needs to be a regional treaty on water rights. Without it, the next wars won't be fought over religion; they'll be fought over the kitchen sink.

- De-escalating Intervention: Outside powers need to stop treating the region like a chessboard. Supporting "our guy" even if he's a tyrant usually ends in a revolution that hurts everyone in the long run.

The Path Forward for the Curious Observer

If you want to understand this better, stop looking at the Middle East as a monolith. A guy in a tech startup in Dubai has a completely different life than a student in Beirut or a farmer in Yemen.

To stay informed, look for sources that focus on local governance and economics rather than just "geopolitical strategy." Follow journalists like Rania Abouzeid or scholars like Rashid Khalidi who provide the deep context that 24-hour news cycles miss. The more you understand the "why" behind the borders and the "how" behind the money, the more the Middle East starts to look less like a mystery and more like a region struggling with very modern, very solvable problems.

Instead of asking why they can't get along, we should probably be asking how we can stop making the situation worse from the outside. The first step is realizing that stability isn't something you can impose with a tank or a treaty drawn in 1916. It has to be grown from the ground up, starting with jobs, water, and a say in how things are run.