You’ve seen them. Those grainy, sepia-toned images of New York City in the 1800s where everyone looks stiff, the streets are caked in mud, and there’s a weird lack of motion. It feels like a different planet. Honestly, looking at a photo of Lower Manhattan from 1860 is more jarring than looking at a sci-fi concept drawing of the year 3000.

The scale of the change is just hard to wrap your head around.

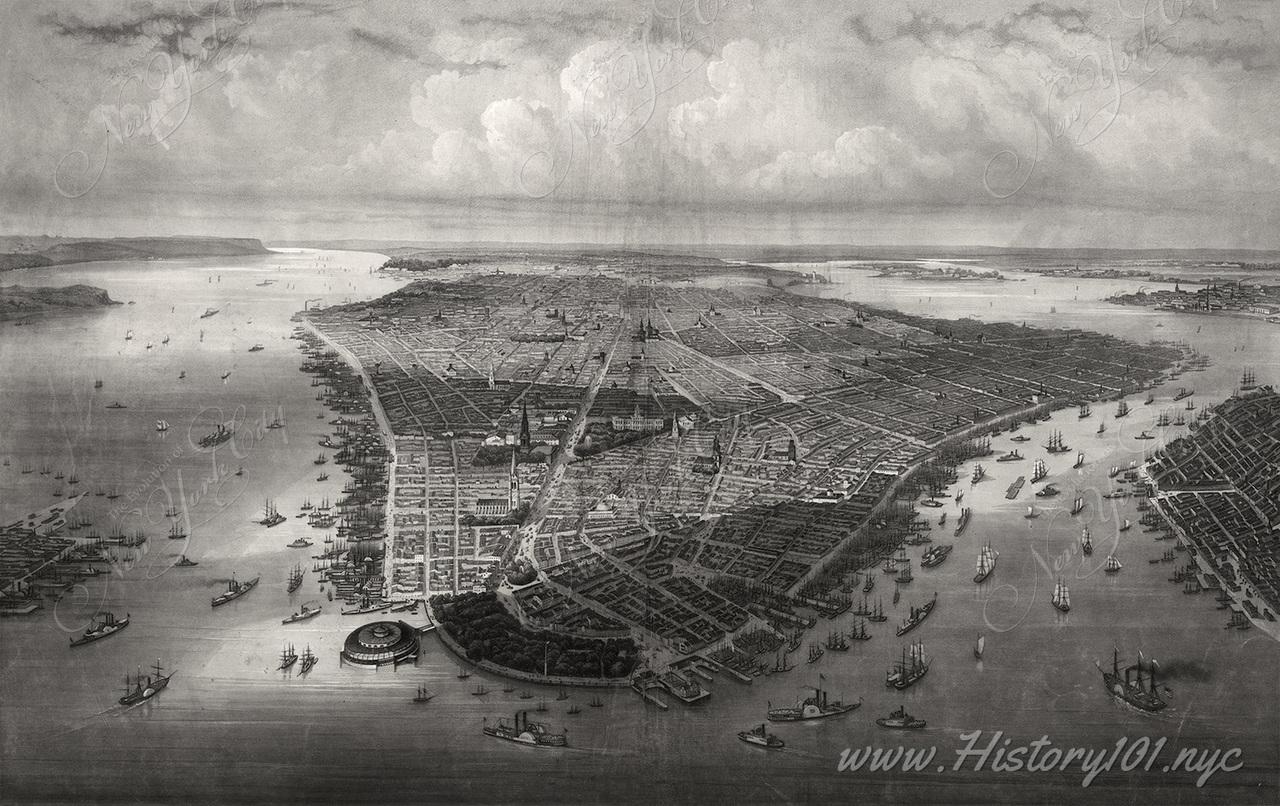

Think about it. In 1800, New York was barely a city; it was a bustling town clinging to the southern tip of Manhattan. By 1899, it was a vertical colossus, a jagged skyline of steel and ego. The camera caught it all. Early photography wasn't about "art" back then—it was about survival and proof.

The Daguerreotype and the Ghostly Streets

The earliest images we have are daguerreotypes. If you’ve ever wondered why the streets look deserted in photos from the 1840s, it isn’t because the city was empty. Far from it. New York was a loud, crowded, smelly mess.

The problem was the exposure time.

Cameras needed several minutes to capture an image. If you walked across the street, you didn't show up. You were a blur that the silver plate simply ignored. Only the buildings stayed still. Because of this, the first images of New York City in the 1800s often look like "Life After People" episodes. It’s haunting. You see a perfectly crisp cobble-stone street, but the thousands of horses and pedestrians that were actually there have been erased by the physics of light.

One of the most famous early shots is of Unitarian Church on Broadway, taken around 1840. It’s arguably the oldest photograph of the city. There’s a strange silence in that image. You can almost feel the dampness of the air.

The Gritty Reality of Five Points

Forget the "Gangs of New York" movie for a second. The real images of the Five Points neighborhood—located where the courthouse district is now—are way more depressing.

Jacob Riis is the name you need to know here. He wasn't just a photographer; he was a guy with a grudge against poverty. His book, How the Other Half Lives, used the brand-new technology of "flash" photography to expose the dark corners of tenements.

Before Riis, photographers stayed outside. It was too dark indoors. But Riis used magnesium flash powder—basically a small, controlled explosion—to light up the rooms of the poor. The faces in those images are startling. You see kids sleeping on top of each other on floorboards. You see the filth. These weren't staged portraits where people wore their Sunday best. These were raw, accidental glimpses into a world that the wealthy New Yorkers uptown didn't even want to admit existed.

📖 Related: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

The "Old Brewery" in Five Points was a legendary slum. It was a massive building that supposedly housed 1,000 people at its peak. When you look at images of that area from the late 1800s, you aren't looking at "quaint" history. You’re looking at a humanitarian crisis captured in silver nitrate.

Broadway and the Birth of the Skyscraper

By the 1880s, things changed. The shutter speeds got faster. Suddenly, we could see the chaos.

Images of New York City in the 1800s started featuring "street life." You see the "whitewings"—the guys in white uniforms whose entire job was to shovel the thousands of pounds of horse manure off the streets every day. Seriously, the horse poop situation was the environmental crisis of the 19th century.

Broadway was the heartbeat.

Looking at photos of the intersection of Broadway and 14th Street from 1890, you see a tangle of wires overhead. Before they moved power lines underground, the sky was literally striped with telegraph and telephone wires. It looked like a giant spiderweb. It’s a detail most period movies get wrong because they want the sky to look pretty. In reality, the sky was a mess of copper.

The Brooklyn Bridge: A Giant Among Ants

The construction of the Brooklyn Bridge (1869–1883) provided some of the most iconic images of New York City in the 1800s.

Seeing the massive stone towers rise while the rest of the city was still mostly four-story brick buildings is wild. The scale is all wrong. It looks like an alien craft landed in a colonial village. Photographers like George P. Hall & Son captured the bridge from high angles, showing just how much it dwarfed the sailing ships in the East River.

The ships are another thing.

South Street Seaport in the 1870s was a forest of masts. It’s easy to forget New York was a port city first. Everything—your coffee, your coal, your clothes—came in on those wooden ships. The photos show the bowsprits of the ships actually hanging over the street, nearly poking into the windows of the warehouses across the way.

👉 See also: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

Why We Misinterpret These Old Photos

We have a habit of romanticizing the past because the photos are "pretty" in a vintage way. But the reality of New York in the late 1800s was loud. It was incredibly loud.

Iron-rimmed wheels on stone streets.

Thousands of horses.

Street vendors screaming.

No mufflers.

When you look at these images, try to "hear" them. The lack of color does us a disservice. It sanitizes the city. New York was a riot of color—red brick, green copper roofs, colorful (and often offensive) posters plastered on every wooden fence.

The people in these photos also look incredibly serious. It wasn't because they were miserable (though many were). It was mostly because of dental hygiene and the tradition of portraiture. You didn't "smile" for a photo any more than you'd smile for a painted portrait. It was a formal record of your existence. When you see a rare "candid" shot from the 1890s where someone is actually laughing, it feels like a glitch in the Matrix.

The Technological Shift: From Plates to Film

Toward the end of the century, George Eastman changed everything.

The Kodak camera came out in 1888. "You press the button, we do the rest."

This is when images of New York City in the 1800s moved away from the "professional" gaze and toward the "amateur" gaze. Suddenly, we have photos of people at Coney Island, or families sitting in Central Park, or just random dogs on the street. These are the photos that actually make the 19th century feel human.

The formal shots of City Hall or the original Penn Station (which wasn't built until 1910, but its predecessors were there) are great for architectural history. But the snapshots—the blurry, poorly framed photos taken by a guy who just bought a Kodak—those are the ones that tell the truth. They show the city's rough edges.

Central Park: The Great Escape

Central Park photos from the 1860s and 70s are particularly interesting because the trees are so small.

✨ Don't miss: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted designed the park, but it took decades to look "natural." In early images, it looks like a barren construction site with some tiny saplings and a lot of mud. People are walking around in full Victorian suits and heavy dresses in the middle of July. You look at those photos and you can almost feel the heatstroke.

But it also shows the desperation for green space. New York was becoming a concrete trap, and the images of the Sheep Meadow (which actually had sheep until 1934) show a city trying to keep its soul while the industrial revolution tried to pave it over.

How to Find "Real" Images Today

If you’re looking for high-quality images of New York City in the 1800s, don’t just use a generic search engine. You’ll get a lot of AI-generated junk or low-res watermarked stuff.

Go to the source.

The New York Public Library (NYPL) Digital Collections is a goldmine. They have thousands of high-resolution scans of the Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views. Stereographs were the VR of the 1800s—two images that looked 3D when viewed through a special device.

The Library of Congress is another one. You can find "Sanborn Maps" and "Detroit Publishing Co." prints that show the city in terrifyingly high detail. You can zoom in on a photo from 1895 and actually read the signs in the shop windows. It’s addictive.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs and Researchers

If you want to truly appreciate or use these historical images, don't just look at them. Analyze them.

- Check the street signs: If you find an old photo, look for the street names. Many streets in Lower Manhattan were renamed or completely eliminated when the grid system took over or when large projects like the World Trade Center (much later) or city parks were built.

- Look at the shadows: You can tell what time of day it was and which way the camera was facing. If the shadows are long and stretching toward the east, you’re looking at a sunset over the Hudson or a sunrise over the East River.

- Identify the "Ghost" Buildings: Find a photo from 1880 and try to find that same spot on Google Street View today. Usually, the only thing left is the "footprint" of the street itself, though in places like the West Village, you might find a surviving townhouse.

- Search for "Nadir" or "Brady": Use specific photographer names like Mathew Brady (famous for Civil War photos but he had a studio in NYC) to find the highest-quality professional portraits and street scenes.

- Verify the Date via Clothing: If the photo is labeled "1850" but you see a woman in a "leg-o-mutton" sleeve (very puffy shoulders), it’s actually the 1890s. Fashion is a more reliable timestamp than the handwritten notes on the back of old prints.

New York in the 1800s wasn't a sepia-toned dream. It was a loud, filthy, vibrating explosion of human ambition. The images we have left are just the silent, frozen echoes of that noise. By looking closely at the details—the mud on the boots, the wires in the sky, and the ghosts of people who moved too fast for the camera—we get a much more honest view of how the modern world was actually born.