The sky didn't just turn orange. It turned a bruised, apocalyptic violet that the camera on your phone probably couldn't even capture correctly. If you've lived through a West Coast summer in the last few years, you know the drill. You wake up, check the air quality index, and look outside to see if the sun is a pale white disk or a terrifying neon marble. Honestly, images of California fires have become a weirdly routine part of our social media feeds, but there is a massive disconnect between a cool-looking photo of a "firenado" and the gritty, localized reality of what those images actually represent for the people on the ground.

Fire season isn't just a season anymore. It's a permanent state of anxiety.

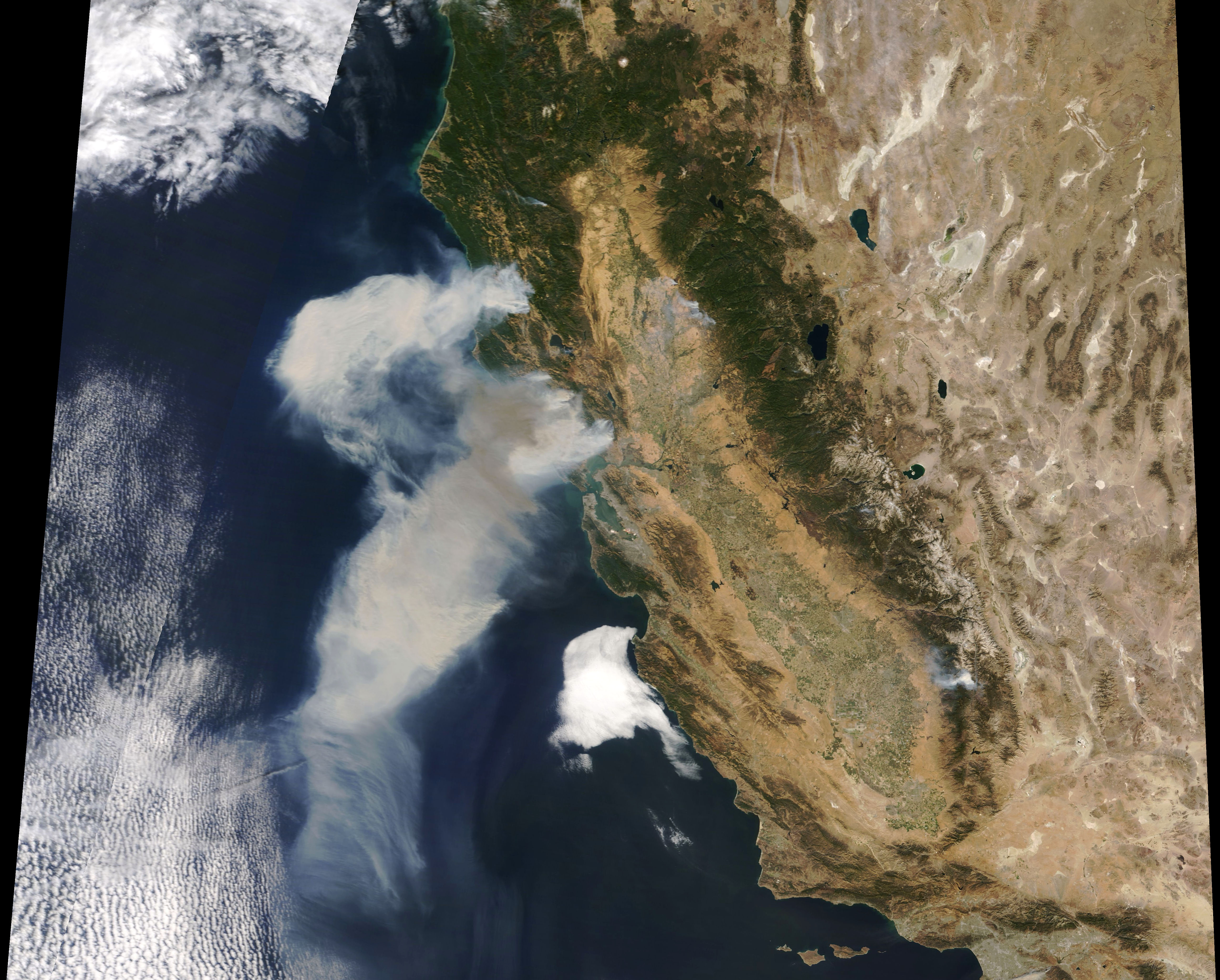

When we talk about images of California fires, we usually see the big stuff. The "money shots." We see the massive wall of flames over the 405 freeway or the charred remains of a vintage sign in Paradise or Greenville. But those photos often miss the nuance of how fire actually moves through a landscape. It’s not always a cinematic wave of heat; sometimes it’s a tiny ember that travels two miles in the wind, lands in a gutter filled with dry leaves, and burns a house from the inside out while the forest around it stays green. That's the scary part. That’s what the high-altitude satellite shots from NASA's MODIS or VIIRS instruments don't show you until the smoke clears and the damage is done.

The Science Behind the "Mars" Filter

Why does every photo from the 2020 North Complex or the 2021 Dixie Fire look like it was taken on another planet? It’s basically physics.

When you have massive amounts of smoke, the particles act as a filter. This is called Mie scattering. Essentially, the smoke particles are just the right size to scatter shorter wavelengths of light—the blues and greens—leaving only the long, red and orange wavelengths to reach your eyes or your camera lens. This is why midday can look like midnight. It’s also why your smartphone camera often struggles to get the white balance right. Have you ever tried to take a photo of a deep orange sky only for the phone to "correct" it back to a muddy grey? It’s frustrating. Professional photographers often have to manually lock their white balance to 5000K just to prove to the world that, yes, the sky really is that color.

💡 You might also like: Quién ganó para presidente en USA: Lo que realmente pasó y lo que viene ahora

Real Examples of Imagery That Changed the Conversation

Think back to the "Orange Skies Day" in San Francisco on September 9, 2020. That wasn't a filter. Those images of California fires—or rather, the secondary effects of them—went viral because they looked like Blade Runner 2049.

- The "Camp Fire" remnants: Photos of the burnt-out shells of cars on Skyway in Paradise. These images served as a brutal reminder of how fast "evacuation" can turn into a trap.

- The Big Basin Redwoods: After the CZU Lightning Complex, images of scorched, hollowed-out ancient trees circulated. People thought the forest was dead. But then, months later, new images showed "epicormic sprouting"—bright green fuzz growing directly out of the blackened trunks. It was a lesson in ecological resilience that a single "fire photo" couldn't capture.

- Satellite heat maps: Seeing the state "bleed" red on a FIRMS (Fire Information for Resource Management System) map provides a scale that a ground-level photo never could.

What the Media Gets Wrong About Fire Photos

There's a certain "disaster porn" element to modern news coverage. We see the flames, we see the orange, and then the news cycle moves on. But the most important images of California fires are often the ones taken six months later.

Landscape recovery is slow. If you look at photos of the Santa Cruz Mountains today, you’ll see a weird mix of silver, "ghost" forests and thick, dangerous undergrowth. The problem is that the public gets used to the "before and after" shots, but they miss the "during." The "during" is the years of soil erosion, the mudslides in Montecito that happen because the vegetation is gone, and the insurance companies pulling out of zip codes because the data in those photos makes the risk look too high.

Risk assessment isn't just for scientists anymore.

📖 Related: Patrick Welsh Tim Kingsbury Today 2025: The Truth Behind the Identity Theft That Fooled a Town

Real estate sites are now integrating fire risk layers directly into their maps. You’re looking at a house in the Berkeley hills, and you see a little "Fire Factor" score. That score is based on the same satellite imagery and historical burn data that fire departments use. It’s a weird world where the "aesthetic" of a fire photo directly impacts your ability to get a mortgage.

The Problem with "Heroic" Imagery

We love a photo of a DC-10 dropping red Phos-Chek retardant. It’s iconic. It feels like we’re winning. But fire experts like Dr. Crystal Kolden have pointed out that these images can be misleading. While air tankers are vital, they don't actually "put out" the fire; they just slow it down so the ground crews can get in. By over-focusing on the "air show" aspect of fire imagery, we sometimes ignore the boring, un-photogenic work of clearing brush, hardening homes, and conducting prescribed burns in the winter.

How to Read a Fire Map Like a Pro

If you actually want to know what’s happening during an active event, stop looking at Getty Images and start looking at data.

- GOES-East/West: These satellites provide near real-time imagery. You can literally watch the smoke plumes develop every 10 to 15 minutes.

- Incident Maps: Look for the "Perimeter" lines. A "contained" line means there is a physical barrier (like a road or a dug trench) that the fire isn't expected to cross. It doesn't mean the fire is out.

- The "Pink" on Maps: In many official maps, the bright pink or red dots are "heat hits." These are detected by infrared sensors from space. If you see a cluster of these moving toward a town, that's your cue to leave, regardless of what the "pretty" photos on the news look like.

California's relationship with fire is complicated. It's a fire-dependent ecosystem that we've tried to turn into a fire-suppressed landscape. The results are visible in every pixel of those terrifying images. We are seeing a century of fuel buildup burning all at once, supercharged by a drying climate.

👉 See also: Pasco County FL Sinkhole Map: What Most People Get Wrong

Practical Steps for Handling the Visual Reality

It is very easy to get "doomscrolling" fatigue when the state is on fire. Honestly, it’s a mental health hazard. If you find yourself staring at images of California fires for hours, you need to pivot from "observing" to "preparing."

Start by "hardening" your own visual space. Take photos of your home—every room, every closet, every serial number on your electronics. This is your "recovery imagery." If the worst happens, having a digital record for insurance is more valuable than any news photo.

Next, check your "defensible space." Go outside and look at your house through the lens of a fire. Do you see "ladder fuels"? These are low-hanging branches that allow a ground fire to climb into the canopy. Cut them. Do you have wooden fences connected directly to your siding? That’s a fuse. Use metal flashing to create a break.

Finally, sign up for localized alerts. Don't rely on Twitter or Instagram for your safety. In California, use the "Watch Duty" app. It’s run by humans (many of them former firefighters and reporters) who vet those images of California fires in real-time. They filter out the rumors and give you the actual coordinates of the "spots." It is the single most useful tool for anyone living in a WUI (Wildland-Urban Interface) zone.

The images aren't going to stop. The sky will probably turn orange again next August or September. But understanding the difference between a dramatic photo and a data-driven map can literally save your life. Stay informed, but don't let the spectacle of the flames distract you from the practical steps of survival.