You’ve probably heard it in a drafty cathedral, or maybe it popped up on a "Classical Focus" playlist while you were trying to survive finals week. It’s four parts. It’s barely two minutes long. Yet, if ye love me by thomas tallis carries a weight that most modern composers would give their right arm to replicate. It’s weird, honestly, how something written in the mid-1500s—a time of literal religious executions and massive political upheaval—feels so incredibly steady.

Tallis wasn't just a composer; he was a survivor. He managed to keep his head (literally) while serving four different English monarchs, all of whom had very different ideas about how God should be worshipped. This specific piece is a product of the English Reformation. It’s what happens when a king tells the church, "Stop with the fancy Latin and the complex layers; I want to understand the words."

The Simple Genius of Thomas Tallis

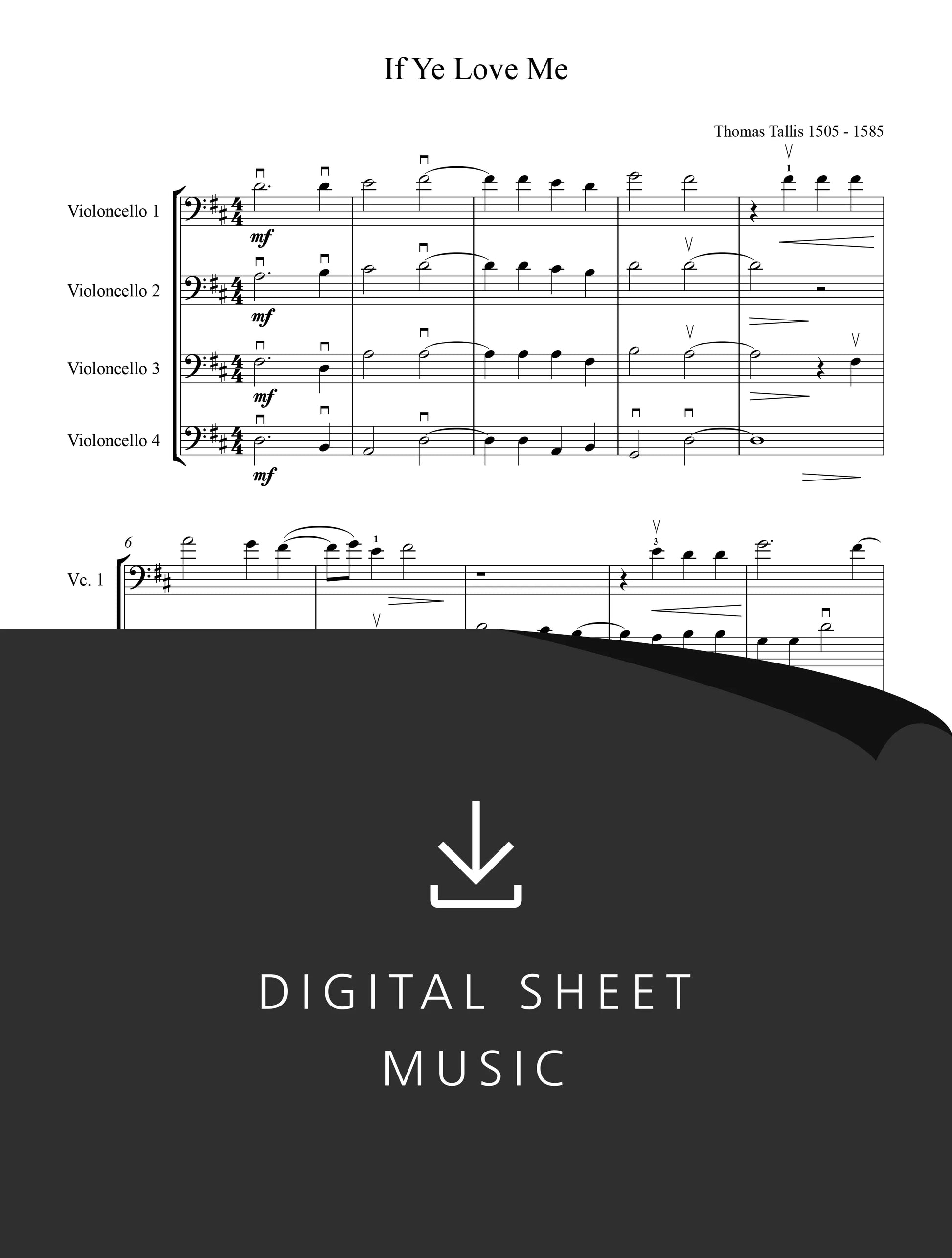

Most people think of Renaissance music as this dense, "holy" wall of sound where you can't tell where one voice ends and the other begins. Tallis changed the game here. In if ye love me by thomas tallis, he uses a style called "homophony" for the opening. Basically, everyone sings the same words at the same time. No confusion. No hiding. It’s a direct musical setting of John 14:15-17.

The beauty of it lies in the shift. After that famous opening line, Tallis lets the voices start to chase each other a bit. It’s called imitation. The tenors start a line, the sopranos mimic it, and suddenly you’re wrapped in this polyphonic texture that feels like a warm blanket. But he never lets it get too messy. He knew Cranmer (the Archbishop of Canterbury) was watching. The mandate was "one syllable per note." It was the 16th-century version of "keep it simple, stupid."

Why the Harmony Hits Different

If you look at the score, it’s written in what we now call the Ionian mode—essentially F major. But it doesn't feel like a bright, poppy major key. It feels grounded. There’s this specific moment on the word "Comforter" where the harmony shifts just enough to make your chest tighten. Tallis was a master of the "English Cadence," a quirky harmonic trick where two different versions of the same note (like a B-flat and a B-natural) clash right before the end of a phrase. It creates this tiny, beautiful friction.

👉 See also: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

It’s that friction that keeps it from being boring.

Musicologists like Peter Phillips, the founder of The Tallis Scholars, have spent decades deconstructing why this specific anthem works. It’s the restraint. Tallis isn't showing off. He’s serving the text. When the choir sings "that he may abide with you forever," the music actually repeats. He uses an AABB structure. He literally makes the music abide by staying in that second section longer than you expect.

A Product of Radical Politics

We can’t talk about this piece without talking about how dangerous it was to write it. Thomas Tallis was a Catholic. He stayed a Catholic his whole life. Yet, he was writing the definitive music for the new Protestant Church of England.

Imagine the stress. One year you’re writing massive, 40-part Latin motets like Spem in alium, and the next, you’re told that Latin is out and simplicity is in. If he messed up, he wasn't just losing a job; he was risking a heresy charge. if ye love me by thomas tallis is a masterclass in professional pivot. He took the "less is more" constraint and turned it into an art form.

✨ Don't miss: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

Common Misconceptions About the Performance

A lot of modern choirs do it wrong. They treat it like a Romantic opera piece with huge swells and vibrato. Honestly? It kills the vibe.

- Vibrato Overload: In the 1560s, these would have been boy singers and men. The sound was "straight." No wobbling. When you hear a group like VOCES8 or Tenebrae do it, they keep the tuning so tight that the overtones start to ring in the room. That’s the "ghost" sound you want.

- The Speed Trap: People tend to drag this piece out because it’s "sacred." If it’s too slow, the phrases fall apart. If it’s too fast, you lose the tenderness of the "if ye love me" plea. It needs to breathe like a human conversation.

- The Dynamic Range: It shouldn't be a constant mezzoforte. The middle section, where the "Spirit of truth" is mentioned, needs a different color. It’s a shift from a command to a promise.

The piece was published in 1560 in Certaine Notes, which was basically the first great collection of English choral music. It survived because it was practical. It only requires four parts (Sutton, Alto, Tenor, Bass), meaning even a small parish choir could pull it off. But it’s the "easy to learn, impossible to master" quality that keeps it in the repertoire of the world's best ensembles.

How to Truly Listen to Tallis

If you want to appreciate the genius of if ye love me by thomas tallis, don't just listen to the top melody. Follow the Bass line. It’s the anchor. It moves with a logic that feels inevitable. Then, listen to the Alto part. Usually, the "boring" middle voice in choral music, but here, Tallis gives the altos these beautiful, descending lines that bridge the gap between the soaring sopranos and the heavy basses.

There is a recording by the King's College Choir that many consider the gold standard, but for a more intimate feel, check out the Stile Antico version. You can hear the individual breaths. It reminds you that this isn't just "old music"—it’s a group of people trying to express something deeply personal about loyalty and spirit.

🔗 Read more: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

The text itself is a bit of a paradox. "If ye love me, keep my commandments." It’s a condition. But the music Tallis wrote doesn't feel conditional. It feels like an embrace. Maybe that was his way of navigating the religious wars of his time—finding the grace in the middle of the legalism.

Actionable Ways to Experience This Piece

If you’re a singer, a listener, or just someone who stumbled upon this, here is how you actually "use" this information:

- For Singers: Focus on the vowels. The English language in the 1500s sounded slightly different, but the goal is "pure" vowels (think "ee" and "ah"). If the vowels aren't matched, the chords won't "lock."

- For Audiophiles: Listen for the "cross-relations." Those tiny harmonic clashes I mentioned earlier are the "spice" of the Renaissance. If you have high-quality headphones, you can actually hear the "beats" in the air when those notes rub against each other.

- For the Curious: Look up the Wanley Partbooks. It’s one of the primary sources for this kind of music. Seeing the original notation—which didn't even have bar lines—changes how you think about the rhythm. It wasn't about a "beat"; it was about the natural flow of the English language.

- Create a Comparative Playlist: Put the Tallis version next to a modern setting of the same text (like the one by Philip Stopford). You'll immediately hear how Tallis used silence and space differently than composers do today.

This isn't just a museum piece. It’s a living bit of DNA from the English choral tradition. Every time you hear a choir at a royal wedding or a funeral, you’re hearing the echoes of the "simplicity" that Tallis perfected in this anthem. He proved that you don't need a hundred instruments to be profound. You just need four voices and a really good understanding of the human heart.

Get a good pair of headphones, find a version by a small vocal consort, and just sit with it. Don't multi-task. Just listen to how the voices enter on "even the Spirit of truth." It’s as close to a musical "hug" as you’re ever going to get from the 16th century.