Magnets are weird. Honestly, even physicists like Richard Feynman have famously struggled to explain the "why" of magnetism to laypeople without falling into a rabbit hole of quantum electrodynamics. But if you’re here, you probably don't care about the math. You want to know how to create a strong magnet because you’re either building a DIY generator, trying to organize a messy workshop, or you’re just a curious person who likes making things click together.

It isn't just about magic rocks.

Most people think you just rub a needle on a fridge magnet and—boom—you’re done. That works for a compass, sure. But if you want a magnet that can actually lift weight or maintain its "stickiness" over time, you have to understand the alignment of domains. Basically, inside a piece of iron or steel, there are these tiny microscopic neighborhoods called magnetic domains. Usually, they're all pointing in different directions, canceling each other out. Your job is to play drill sergeant and force them all to point the same way.

The Electrical Method: Using Solenoids for Real Power

If you want a truly beefy magnet, you have to use electricity. This is how industrial-strength electromagnets are made. You take a conductive wire—usually copper with a thin enamel coating—and wrap it tightly around a "core." This core should be a ferromagnetic material, like a soft iron bolt. When you run a DC current through that coil, it creates a magnetic field.

The strength of this field is determined by a few variables. First, there's the number of turns in your coil. More loops equal more "push." Then there's the current, measured in Amperes. If you double the current, you roughly double the strength, provided you don't melt the wire. This is governed by Ampere’s Law, which relates the integrated magnetic field around a closed loop to the electric current passing through the loop.

Why the Core Material Changes Everything

Don't just grab any old piece of metal. If you use a stainless steel bolt, you’re going to be disappointed. Most stainless steel is austenitic, meaning its crystal structure doesn't play nice with magnetic fields. You want "soft" iron. In the magnetism world, "soft" doesn't mean squishy; it means the material can be magnetized and demagnetized easily. This makes it perfect for electromagnets.

However, if you want a permanent magnet—one that stays strong after you turn the power off—you need "hard" magnetic materials. Think high-carbon steel or alloys like Alnico (Aluminum, Nickel, Cobalt). These materials have "high coercivity," which is just a fancy way of saying they are stubborn. Once you force those internal domains to line up, they stay there.

The Neodymium Reality Check

Let's talk about the elephant in the room: Rare-earth magnets. If you're looking at how to create a strong magnet at home that rivals the ones you buy online, the truth is a bit sobering. You cannot easily "create" a Neodymium (NdFeB) magnet in a garage. These are manufactured through a process called powder metallurgy.

Manufacturers take neodymium, iron, and boron, grind them into a fine powder, and then—this is the crazy part—they press that powder into a mold while exposing it to a massive magnetic field to pre-align the particles. Then they sinter it (heat it up just below the melting point) in a vacuum. It’s a high-tech bake-off.

You can, however, "recharge" a weakened neodymium magnet. If you have a high-end magnetizer, which is essentially a massive bank of capacitors that dumps a huge amount of energy into a coil in a split second, you can realign those domains. But for most of us, creating one from scratch is out of reach. We stick to electromagnets or steel-based permanent magnets.

🔗 Read more: Finding ln6: What Most Students Get Wrong About Natural Logs

Heating and Beating: How to Kill Your Progress

You can't talk about making magnets without talking about how to destroy them. Heat is the enemy. Every magnetic material has what's called a Curie temperature. For iron, it’s about 770°C (1,418°F). If you heat your magnet past this point, the thermal agitation becomes so violent that the domains lose their alignment. They start pointing in random directions again, and your magnet becomes just a hot piece of metal.

Even dropping a magnet can weaken it. This is called mechanical shock. Each time it hits the floor, the microscopic domains get jarred. Over time, this leads to a weaker overall field. If you’re trying to maintain a DIY magnet, treat it like glass.

Stacked Flux: The Secret of the Halbach Array

If you want to know how to create a strong magnet that feels like it’s punching above its weight class, you need to look into the Halbach Array. This is a specific arrangement of smaller magnets that augments the magnetic field on one side while almost cancelling it out on the other.

Think about those flat kitchen magnets that stick to the fridge but won't stick to each other on their "top" side. That’s a basic Halbach-style arrangement. By rotating the magnetic orientation of each piece by 90 degrees as you lay them out, you "bend" the magnetic flux lines. This concentrates the pull. It’s how maglev trains work and how those tiny brushless motors in your drone get so much torque.

Testing Your Results

How do you know if you actually succeeded? You need a Gauss meter (or a Teslameter). If you don't want to spend $100 on a dedicated device, most modern smartphones actually have built-in Hall effect sensors used for the compass. There are plenty of free apps that let you read the raw data from these sensors.

Keep in mind, these sensors are usually designed for the Earth's relatively weak magnetic field (about 0.25 to 0.65 Gauss). A strong neodymium magnet might be 10,000 Gauss or more. If you put a strong magnet right against your phone, you might not break it, but you'll definitely "peg" the sensor and get a useless reading. Test from a distance and use the Inverse Square Law to estimate the strength at the surface.

Practical Steps for a DIY High-Power Magnet

To actually build something functional today, follow these specific steps. This isn't a toy; it's a basic engineering project.

- Source a high-quality core. Look for a large, grade 2 or grade 5 iron bolt. Avoid "zinc-plated" if possible, though it's not a dealbreaker. The thicker the core, the more "magnetic flux" it can carry before it saturates.

- Use Magnet Wire. This is different from the plastic-coated wire in your walls. Magnet wire has a micro-thin resin coating. This allows you to wind hundreds of turns in a very small space. The closer the wire is to the core, the more efficient the magnet.

- Calculate your Power. Use a 12V lead-acid battery or a high-current DC power supply. If you use a 9V battery, it will die in minutes. Be careful—coils are inductors. When you disconnect the power, the collapsing magnetic field can cause a "back EMF" spark. Use a diode in your circuit to prevent this if you're feeling fancy.

- Manage the Heat. Your coil is basically a heater. If it gets too hot to touch, turn it off. The resistance of copper increases with temperature, which actually makes your magnet weaker as it runs.

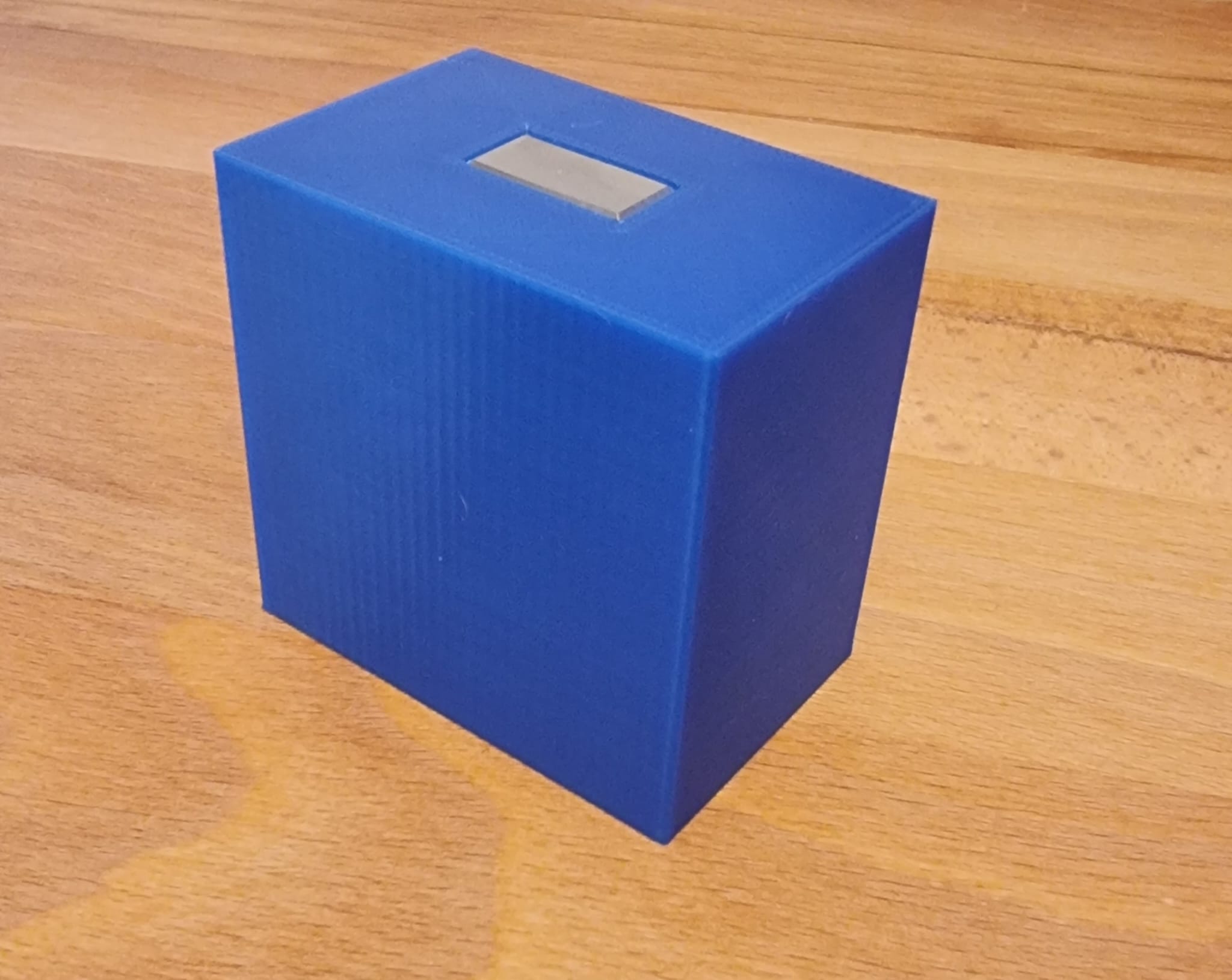

- Potting the Magnet. If you want it to last, wrap the finished coil in epoxy or heavy-duty electrical tape. This prevents the wires from vibrating (which they will do) and wearing through their insulation.

The world of magnetism is surprisingly deep. You start by rubbing a nail on a magnet and end up studying the spin of electrons in the 3d subshell of transition metals. If you're serious about creating the strongest field possible, focus on the quality of your copper windings and the purity of your iron core. That is where the real power lies.