Memories are weird. We remember our childhoods in vibrant, chaotic color—the neon orange of a popsickle, the specific faded denim of a dad's jacket—but our family history is stuck in grayscale. It creates this weird emotional distance. You look at a photo of your great-grandfather and he looks like a statue or a character from a movie, not a guy who probably had a favorite shirt and a sunburn.

Learning how to colorize black and white photos isn't just a technical trick for your Instagram feed. It’s a way to bridge that gap. Honestly, it's about making history feel like it actually happened to real people.

But here’s the thing: doing it right is surprisingly hard. You’ve probably seen those "one-click" AI colorizers. They’re okay. Sorta. But they usually turn everyone’s skin a weird, sickly peach and leave the background looking like a muddy mess of browns and grays. If you want a photo to look like it was actually shot on Ektachrome in 1952, you have to understand the interplay between light, historical accuracy, and the modern software we use to bring these images back to life.

The Problem with Automatic Colorization

Let's get real for a second. AI is great, but it’s a bit of a guesser. When you upload a photo to a service like MyHeritage or Palette.fm, the algorithm looks at the luminance values—the brightness—and compares them to millions of other photos. It says, "Okay, this shape looks like a tree, and trees are usually green, so I’ll make this green."

That’s fine for a quick fix.

However, AI can’t know that your grandfather’s 1968 Mustang was actually "Acapulco Blue" and not "Candyapple Red." It doesn't know the specific regimental colors of a Civil War uniform or the exact shade of a 1940s lipstick. This is where the human element comes in. To truly master how to colorize black and white photos, you need to be part historian and part digital painter.

Why luminosity is your biggest enemy

The biggest mistake beginners make is ignoring the original lighting. In black and white photography, contrast is everything. If you just slap a layer of color over a high-contrast image without adjusting the blend modes, the colors look "painted on" rather than part of the scene. It looks fake. Cheap. You want the color to feel like it’s vibrating within the grain of the film, not sitting on top of the glass.

💡 You might also like: Why Everyone Is Talking About the Gun Switch 3D Print and Why It Matters Now

Modern Tools: From Photoshop to AI

You have two main paths. The first is the manual route using Adobe Photoshop. This is the gold standard used by professionals like Marina Amaral, who famously colorized images of the Holocaust and the American Civil War.

The second path is the AI-assisted route.

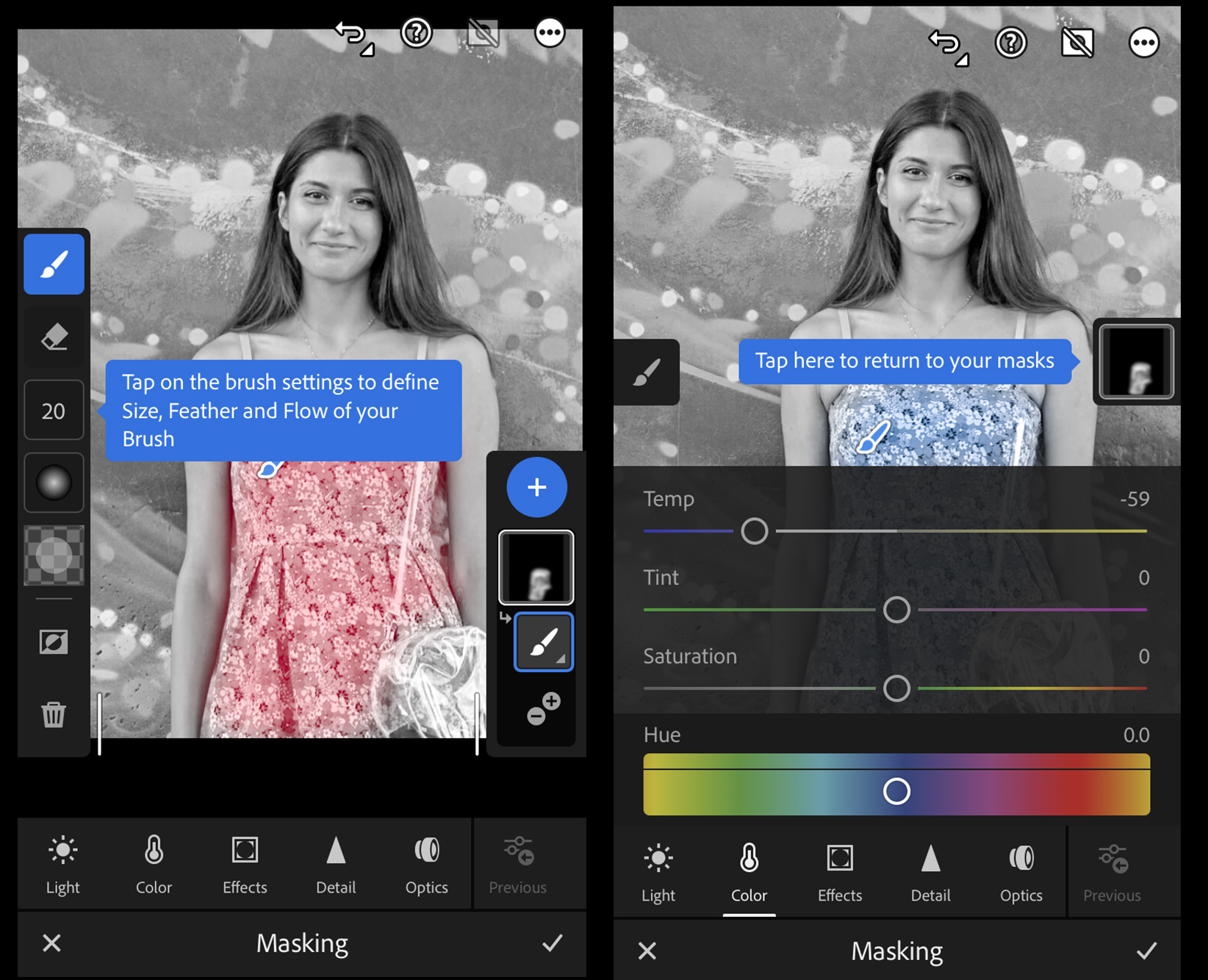

Actually, most pros use a hybrid. They start with an AI base to get the "bulk" of the colors in place and then spend hours—literally hours—masking and refining the details. If you’re just starting, you’ll probably want to experiment with Photoshop’s "Neural Filters." It’s hidden in the Filter menu. You click "Colorize," and Adobe’s Sensei AI does a decent first pass.

But don't stop there. Please.

Take a look at the skin tones. Human skin isn't one color. It’s a map of reds, blues, and yellows. There’s "subsurface scattering" happening, where light hits the skin and bounces around under the surface. If you don't add a little bit of red to the ears, the knuckles, and the tip of the nose, your subject is going to look like a wax figure.

Essential Software Checklist

- Adobe Photoshop: Still the king for layer control.

- GIMP: The free alternative that’s powerful but has a learning curve that feels like climbing a vertical wall.

- Affinity Photo: A great mid-range option that handles "Live Filters" beautifully.

- DeOldify: An open-source deep learning project that is arguably the best raw AI engine out there.

Step-by-Step: The Manual Method

Let’s say you’ve got a scanned photo of your grandma. It’s a 1945 silver gelatin print. It’s crisp but colorless.

📖 Related: How to Log Off Gmail: The Simple Fixes for Your Privacy Panic

First, you need to clean it. You can't colorize dust. Use the Spot Healing Brush to get rid of scratches and those tiny white specks.

Once it’s clean, you start adding "Solid Color" adjustment layers. Change the blend mode to Color. This is the secret sauce. The "Color" blend mode keeps the brightness of the original photo but applies the hue and saturation of your new layer.

Now comes the tedious part: masking. You’ll be painting with a black brush on a white mask to hide the color where it shouldn’t be. You do this for the skin. Then a new layer for the hair. Then a new layer for the dress. By the time you’re done, you might have 50 layers. It sounds insane. It kinda is. But that’s how you get the depth that makes people stop scrolling.

Finding the right colors

Don't guess. If you’re colorizing a photo from the 1920s, look up 1920s fashion catalogs. Look at the Sears Roebuck archives. If there’s a car in the background, find the make and model and look up the factory paint codes.

I once saw a guy colorize a photo of a 1930s baseball game and he made the grass neon green. It looked like a video game. Old grass in a stadium without modern irrigation was often patchy, yellowish, or deep forest green. Details matter.

The Ethical Debate: Should We Even Do This?

Not everyone thinks colorizing is a good idea. Purists argue that it’s a form of "cultural vandalism." They believe that if a photographer like Ansel Adams or Dorothea Lange chose to shoot in black and white, we should respect that artistic choice.

👉 See also: Calculating Age From DOB: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

There’s also the risk of "smoothing over" history. Black and white photos feel old, which reminds us that the events happened a long time ago. When you colorize them, they feel modern. Some historians worry this makes us lose the "otherness" of the past.

But I disagree.

I think colorization makes us realize that the people in those photos weren't living in a gray world. They saw the same blue sky we see. They felt the same warmth of the sun. Colorizing is a way of saying, "I see you." It’s an act of empathy.

When to leave it alone

If the photo is an intentional piece of fine art—think Henri Cartier-Bresson—just leave it. The composition was designed around light and shadow. Adding color usually just ruins the balance. But for family snapshots? Go for it.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Over-saturation: People in the past didn't wear neon. Natural dyes and older film stocks were much more muted. Keep your saturation levels lower than you think they need to be.

- Uniform Skin Tones: As I mentioned, skin is complex. Use a soft brush with low opacity (around 10%) to build up layers of pink and peach.

- The "Halo" Effect: When you paint color near an edge, it often bleeds over. Zoom in to 300%. Clean up those edges. If the blue from the sky is bleeding into a person's hair, it looks amateur.

- Ignoring the Black Point: Don't let your "pure blacks" become colored. Shadows should stay mostly neutral. If the deep shadows under a chair are suddenly bright purple, the illusion is broken.

Actionable Next Steps for Your First Project

If you're ready to try how to colorize black and white photos yourself, don't start with a complex group photo. You'll burn out in twenty minutes.

- Select a high-resolution scan. Use a portrait with a simple background. A photo with a 600 DPI scan is your baseline; anything lower will just look pixelated when you try to paint the details.

- Try an AI base first. Use a tool like Palette.fm to get a general idea of the color palette. Download that result.

- Import both into your editor. Put the original B&W on the bottom, the AI version in the middle, and your manual layers on top.

- Fix the skin first. Use the AI as a guide, but manually paint in the "life" of the face. Focus on the eyes—keep the whites of the eyes slightly off-white, never pure white.

- Reference real-world objects. If there is a Coke bottle or a specific brand of cigarettes in the photo, find a color reference of that object from the same era to sample your colors from.

- Add a Grain Layer. After colorizing, the image can sometimes look too "clean." Adding a 1-2% noise or grain layer over the top helps unify the new colors with the original film texture.

This process is a rabbit hole. You start with one photo of your grandmother and suddenly it’s 2 AM and you’re researching the exact shade of olive drab used for paratrooper jackets in 1944. But when you finally click that "Before and After" toggle and see a person come to life, it’s worth every second. You aren't just editing a file; you're reclaiming a moment from the fog of time.