Bob Dylan was only 21 when he sat in the Commons Theater in Greenwich Village and scribbled out a song that would eventually outlive him. It’s wild to think about. A kid with a harmonica and a scratchy voice wrote a series of rhetorical questions that became the anthem for every major social movement of the last sixty years. When people search for how many roads must a man walk down lyrics, they aren't usually just looking for the words to sing along at a campfire. They’re looking for why those specific words feel like a punch in the gut even in 2026.

The song is "Blowin' in the Wind." It’s basically the "Old Testament" of folk music.

Dylan didn't invent the melody, though. He lifted it from an old spiritual called "No More Auction Block," a song sung by former slaves. He took that weight of history and condensed it into a few verses that never actually give you an answer. That’s the genius of it. He tells you the answer is "blowin' in the wind," which is just a poetic way of saying it’s right there in front of your face, but you’re too busy looking away to see it.

The Actual Meaning Behind the Roads and the Walking

The opening line of the how many roads must a man walk down lyrics sets a massive, sweeping stage. It asks about the "roads" a man must travel before you call him a man. This isn't about hiking or road trips. It’s about dignity.

In 1962, when this was released on The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, the United States was a pressure cooker. The Civil Rights Movement was hitting a fever pitch. Dylan was hanging out with people like Suze Rotolo—his girlfriend at the time who is on the album cover—and she was deeply involved in CORE (Congress of Racial Equality). She was the one who really pushed his political consciousness. When he asks how many roads a man must walk, he’s asking how much suffering a Black man in America has to endure before the system recognizes his humanity.

It’s a heavy question for a 21-year-old from Minnesota.

But it’s also remarkably simple. Dylan uses three distinct metaphors: the road, the sea, and the sky.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

- The Road: Human experience and the struggle for personal identity.

- The Dove: Peace, obviously, but specifically the idea of peace finding a place to rest.

- The Cannonballs: The sheer stupidity and waste of war.

Honestly, the "cannonballs" line is where the song transitions from a civil rights song to a universal anti-war manifesto. He asks how many times they must fly before they’re forever banned. Think about the era. This was the Cold War. People were building fallout shelters in their backyards. The Cuban Missile Crisis was just around the corner. The song tapped into a primal fear that we were going to blow ourselves up for no reason.

Why the Lyrics Feel Different in the 2020s

You’d think a song from 1962 would feel like a museum piece by now. It doesn’t.

If you look at the how many roads must a man walk down lyrics today, they apply to different but equally pressing anxieties. We’re still asking how many times a man can "turn his head and pretend that he just doesn't see." Back then, it was Jim Crow and Vietnam. Today, it’s the climate crisis, the refugee emergency, or the way we treat the unhoused. The "turning of the head" is the most convicting part of the whole song.

Dylan isn’t just blaming "the man" or the government. He’s blaming the listener.

The Mystery of the Answer

People have debated what "blowin' in the wind" actually means for decades. Some critics, like those at Rolling Stone or various Dylan biographers like Clinton Heylin, suggest it means the answer is elusive and impossible to catch. You reach for it, and it flutters away.

But there’s a different interpretation that feels more "Dylan."

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

The answer is obvious. It’s invisible, like the wind, but it’s everywhere. It’s hitting you in the face. You don’t need a PhD or a political science degree to know that war is bad or that people deserve rights. You just have to stop ignoring what’s right there.

The Evolution of the Lyrics Through Cover Versions

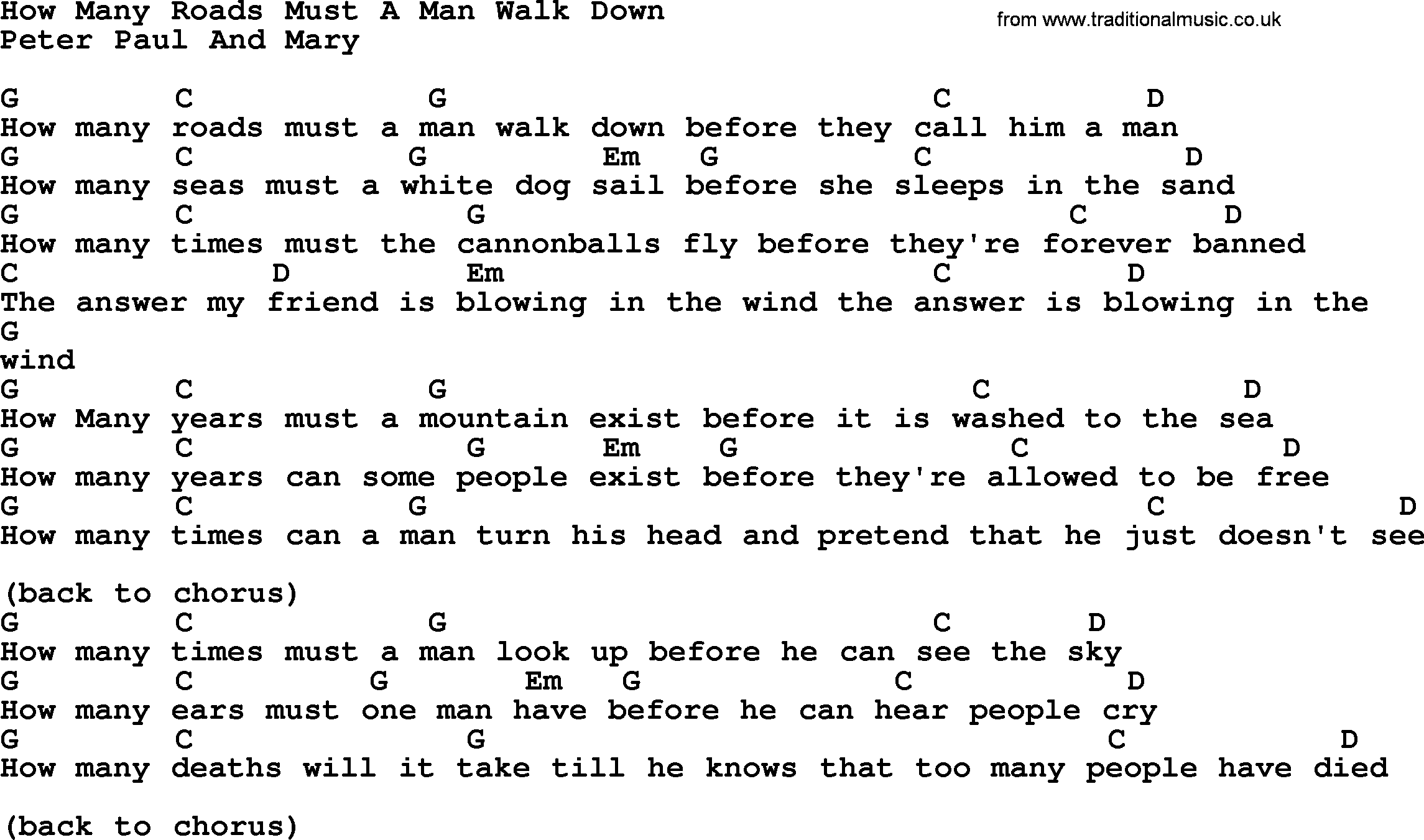

Dylan’s version is iconic, sure. It’s raw. But the song really took flight when Peter, Paul and Mary covered it. They smoothed out the edges. They made it a hit. Suddenly, the how many roads must a man walk down lyrics were being sung by middle-class families in their living rooms.

Then you had Stevie Wonder.

Stevie’s 1966 version changed everything. When a Black man in the middle of the 1960s sings, "How many years can some people exist before they're allowed to be free?" it’s no longer a philosophical question. It’s a demand. It’s a protest. It’s visceral. Stevie brought a soul and a grit to the song that Dylan, for all his brilliance, couldn’t provide as a white kid from the Midwest.

Then there’s Joan Baez. Her relationship with Dylan is the stuff of legend, but her voice gave these lyrics a crystalline, almost angelic authority. When she sang it, it sounded like a prophecy.

Facts vs. Myths: What Most People Get Wrong

There’s a persistent rumor that Bob Dylan didn't actually write the song. Some people claimed for years that a high school student named Lorre Wyatt wrote it and Dylan bought the rights.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

That’s total nonsense.

It was a classic piece of "tall tale" urban legend. Wyatt eventually admitted he didn't write it; he had just performed it before Dylan’s version became a global smash, and people assumed he was the author. Dylan has his flaws—he’s definitely been "liberal" with how he uses old folk melodies—but the how many roads must a man walk down lyrics are 100% his poetry.

Another misconception is that the song was written specifically for the March on Washington in 1963. While Dylan did perform it there, he’d actually written it over a year prior. It just happened to be the perfect song for the moment. It’s one of those rare instances where art and history collide perfectly.

How to Internalize These Lyrics Today

If you’re digging into these lyrics, don't just treat them as a "greatest hit." Treat them as a challenge. The song is structured as a series of "how many" questions, but it never provides a number.

- How many roads?

- How many seas?

- How many years?

The point is that there is no number. There is no point where we say, "Okay, we’ve walked enough roads, now we can stop being decent human beings." The walking is the point. The awareness is the point.

Actionable Takeaways for the Modern Listener

To really understand the weight of these lyrics, you sort of have to look at them through a few different lenses:

- Contextual Research: Listen to the original spiritual "No More Auction Block." You’ll hear the DNA of Dylan’s song. It grounds the lyrics in the history of the Black struggle for freedom, which makes the "roads" metaphor much more powerful.

- Comparative Listening: Play Dylan’s original Freewheelin' version back-to-back with Stevie Wonder’s 1966 version. Notice how the meaning shifts based on the identity of the singer. It’s a masterclass in how delivery changes intent.

- Reflective Writing: Look at the stanza about the "man who turns his head." Identify one thing in your own life or community that you’ve been "turning your head" away from. The song isn't just a poem; it's an indictment of apathy.

- Lyric Analysis: Pay attention to the lack of "I" in the song. Dylan doesn't say "I think" or "I believe." He uses universal terms. This is why the song works in any country and any language. It’s not about one man’s opinion; it’s about a collective human condition.

The how many roads must a man walk down lyrics will likely be around for another hundred years. Not because they’re catchy—though they are—but because humanity seems to have a very hard time answering the questions they pose. We’re still walking. The wind is still blowing. And we’re still, quite often, turning our heads.