Let’s be real for a second. If you mention House of Cards Season 2 to anyone who watched TV in 2014, they don't think about the policy debates or the diplomatic maneuvering. They think about the subway platform. They think about Zoe Barnes. That single moment, occurring just minutes into the premiere, didn't just shock the audience—it fundamentally changed how we consumed streaming television. It was the moment Netflix proved it could be just as ruthless as HBO.

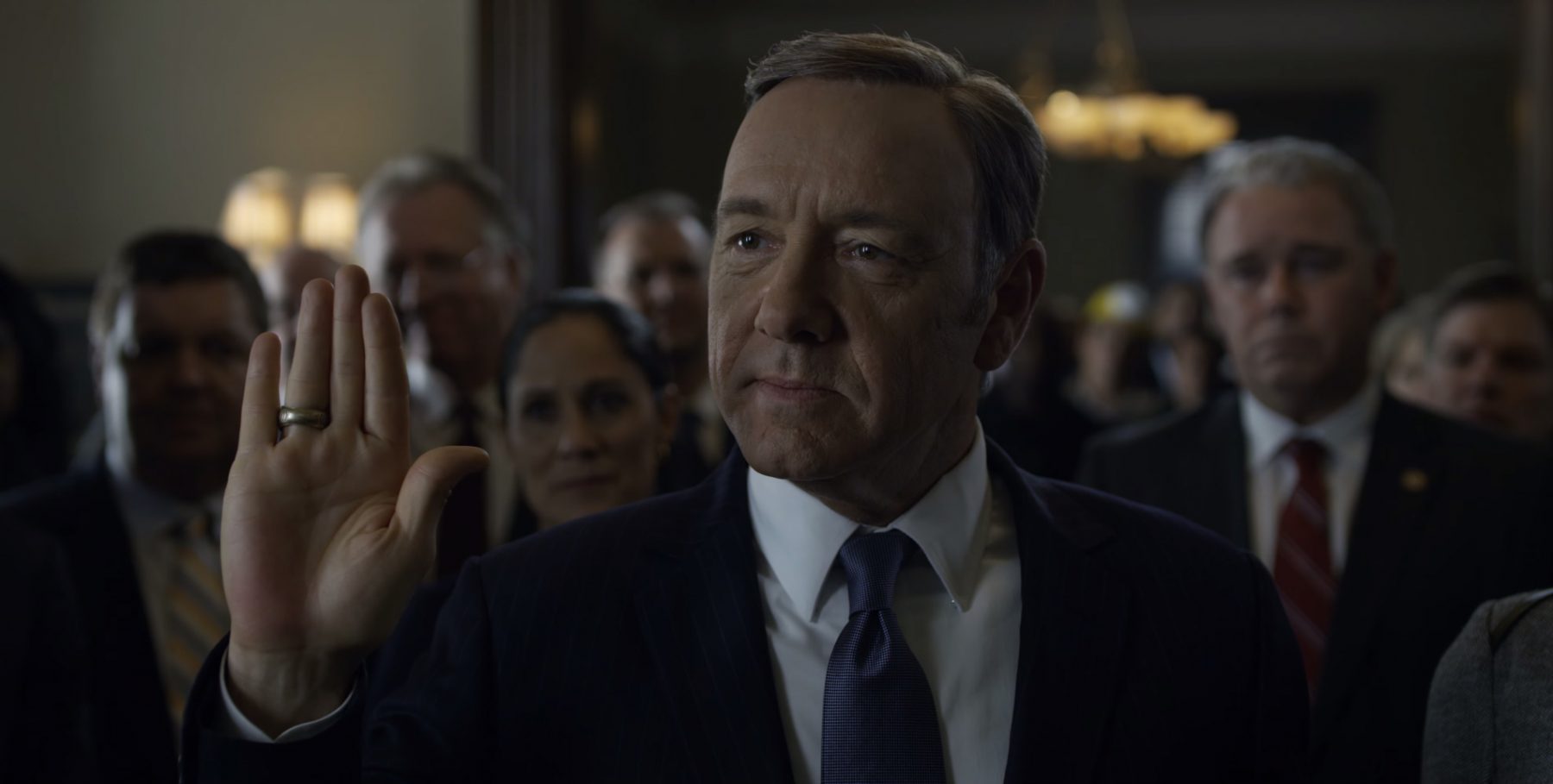

Frank Underwood, played by Kevin Spacey with that dripping, fourth-wall-breaking Southern drawl, was no longer just a disgruntled Whip. He was the Vice President of the United States. But as we quickly learned, the climb to the top is significantly easier than staying there once you've left a trail of bodies in your wake. The second season is a masterclass in claustrophobic storytelling. While the first season felt like a broad expansion of power, the second feels like the walls are closing in, even as Frank gets closer to the Resolute Desk.

The Brutal Efficiency of the Premiere

Most shows wait until a season finale to pull a stunt like killing off a lead character. Beau Willimon, the showrunner at the time, decided to do it in episode one. By shoving Zoe Barnes in front of a Washington Metro train, the show signaled that the rules had changed. The investigative journalism plotline that had been a pillar of the first season was effectively decapitated.

It was a gutsy move. It told the audience that no one—not even the characters you thought were protected by "plot armor"—was safe from Frank’s pragmatism. This wasn't just about shock value, though. It served a narrative purpose. It isolated Frank. It removed the one person who truly knew his darkest secrets, but it also created a vacuum of paranoia that defined the rest of the season’s thirteen episodes.

Raymond Tusk and the Battle of Billionaires

If Season 1 was Frank versus the "Old Guard" of DC, Season 2 was a heavyweight bout between Frank and the private sector. Enter Raymond Tusk. Gerald McRaney played Tusk with a chilling, understated stillness that made him a perfect foil for Frank’s theatricality. Tusk wasn't a politician; he was a billionaire with the ear of President Garrett Walker.

This is where the show got into the weeds of US-China relations, trade wars, and money laundering. For some, the "bridge project" and the back-and-forth over Samshon or rare earth minerals felt a bit dry. Honestly, it was. But it was necessary. It grounded the melodrama in the reality of how global power actually functions. It’s not just about votes; it’s about who controls the flow of capital.

The conflict between Underwood and Tusk was basically a proxy war for the soul of the Presidency. President Walker, played by Michel Gill, often felt like a man caught between two lions. He was portrayed as a "good man" who was fundamentally too soft for the environment he inhabited. Watching Frank slowly erode Walker’s trust in Tusk—while simultaneously appearing to be Walker’s only loyal ally—was like watching a slow-motion car crash. You knew where it was going, but you couldn't look away.

📖 Related: Colin Macrae Below Deck: Why the Fan-Favorite Engineer Finally Walked Away

Claire Underwood’s Evolution

While Frank was busy with trade wars, Claire was fighting a much more personal battle. Robin Wright’s performance in House of Cards Season 2 is arguably the series' peak. The introduction of the sexual assault storyline involving General Dalton McGinnis added a layer of vulnerability to Claire that we hadn't seen before.

It wasn't just about trauma, though. Because this is House of Cards, everything is a weapon. Claire’s decision to go public with her past wasn't purely an act of healing; it was a calculated political maneuver to pass a bill addressing military sexual assault. It showed that she was just as capable of instrumentalizing her own life as Frank was.

The dynamic between Frank and Claire remained the show’s strongest asset. They weren't a traditional couple. They were a partnership. A firm. There’s a scene where they share a cigarette at the window—a recurring motif—where the silence says more than the dialogue ever could. They are the only two people in the world who truly see each other, which makes their occasional betrayals even more devastating.

Jackie Sharp and the New Generation

We also have to talk about Jackie Sharp. Molly Parker stepped into the role of the new House Majority Whip, and she was a revelation. She was a combat veteran with a literal "soldier’s heart" and a metaphorical killer instinct. Her arc in Season 2 served as a mirror to Frank’s.

She had to decide how much of her soul she was willing to shave off to maintain her position. Her relationship with Remy Danton (Mahershala Ali) added a layer of "human" complication that the Underwoods had long since evolved past. Remy, working for Tusk, was the bridge between the political and the corporate, and his chemistry with Jackie provided some of the season's few moments of genuine heat.

Why the Pacing Worked (And Sometimes Didn't)

The middle of the season—roughly episodes four through eight—can be a bit of a slog if you aren't into the minutiae of Senate procedure. The whole "entitlements" debate and the government shutdown subplot felt very "ripped from the headlines" of the early 2010s. It was a bit on the nose.

👉 See also: Cómo salvar a tu favorito: La verdad sobre la votación de La Casa de los Famosos Colombia

However, the show used these procedural hurdles to build tension. The stakes weren't just "does Frank win?" It was "how many people does Frank have to destroy to win a minor procedural vote?" The answer was usually "everyone."

The tension culminated in the "Three-Way" episode, which remains one of the most discussed and polarizing moments of the series. It was a bizarre, unexpected turn that signaled the Underwoods were moving into a phase of total decadence. They had conquered the political world; now they were conquering the boundaries of their own domestic life. It was weird. It was uncomfortable. It was perfectly in character for two people who viewed the world as their playground.

The Downfall of Doug Stamper

If Frank is the brain of the operation, Doug Stamper is the hands. And in Season 2, those hands got very, very dirty. Michael Kelly’s portrayal of Doug is a masterclass in repressed intensity. His obsession with Rachel Posner—the sex worker who could link Frank to Peter Russo’s death—became his undoing.

Doug’s arc in this season is a tragic one. He is a recovering alcoholic who replaces his addiction to booze with an addiction to control. He tried to "save" Rachel while simultaneously keeping her a prisoner. It was a toxic, haunting dynamic that ended with Doug lying in the woods, presumably dead (though later seasons would walk that back). It showed that even the most loyal foot soldier can't survive the radioactive blast radius of the Underwoods for long.

Visuals and Atmosphere

Director David Fincher’s influence was still felt heavily in Season 2, even as other directors took the helm. The color palette remained a cold, sickly wash of grays, blues, and ambers. The lighting in the Vice President's residence always felt dim, as if the characters were constantly hiding in the shadows.

The cinematography reinforced the theme of the season: transparency is a myth. Everything happens in the corners. Every conversation is a negotiation. Every look is a threat. The show didn't just tell you that DC was a dark place; it made you feel it in the low-contrast, sharp-edged visuals.

✨ Don't miss: Cliff Richard and The Young Ones: The Weirdest Bromance in TV History Explained

What Most People Get Wrong

A common criticism of House of Cards Season 2 is that Frank’s rise was "too easy." Critics argued that his enemies were too incompetent or that the plot relied too much on coincidences.

I disagree.

The point wasn't that Frank was a genius; it was that the system was broken. Frank didn't succeed because he was smarter than everyone else; he succeeded because he was willing to go further than everyone else. He was the only one playing a zero-sum game while everyone else was trying to build a consensus. The season wasn't a celebration of his brilliance; it was an indictment of a political structure that rewards sociopathy.

Actionable Takeaways for the Modern Viewer

If you’re revisiting the season or watching it for the first time, keep these points in mind to truly appreciate the depth of the writing:

- Watch the Fourth Wall: Pay attention to when Frank stops talking to the camera. In the middle of the season, he does it less. It’s as if he’s so overwhelmed by the Tusk conflict that he doesn't have time for us. When he returns to us at the end, it’s a chilling reminder that we are his only "true" confidants.

- Track the "Cufflinks": There are subtle visual cues throughout the season—gifts, jewelry, accessories—that signal who is currently in someone’s pocket.

- The Power of Silence: Some of the best scenes involve Claire just sitting in a room. Robin Wright does more with a slight tilt of her head than most actors do with a three-page monologue.

- Analyze the Cashew Subplot: Gavin Orsay (Jimmi Simpson) and his guinea pig, Cashew, seem like they’re in a different show entirely. But this subplot is a crucial look at the rise of the surveillance state and the vulnerability of digital privacy—themes that became even more relevant in the years following the show’s release.

The season ends with "The Knock." Two raps on the desk in the Oval Office. Frank has arrived. He has manipulated a sitting President into resigning, neutralized a billionaire rival, and buried his past (literally and figuratively). It is the peak of the series. While later seasons struggled to find a new mountain to climb after Frank reached the summit, Season 2 remains a perfectly paced ascent into the heart of darkness.

If you want to understand the "Prestige TV" era of the 2010s, you have to understand this season. It was cynical, brutal, and utterly addictive. It didn't care if you liked the characters. It only cared if you were watching. And we were.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

To get the most out of your rewatch, track the specific legal maneuvers Frank uses to manipulate the 25th Amendment. Cross-referencing these with actual Constitutional law reveals just how much homework the writers did to make the impossible seem plausible. You can also look into the production notes regarding the "Subway Scene," which required immense coordination with the DC Metro to film during off-hours to maintain the secrecy of the plot twist.

The real legacy of this season isn't the plot, though. It’s the way it shifted the power dynamic from traditional networks to the viewers, allowing for a darker, more complex narrative that didn't have to worry about "likability" or commercial breaks. That, more than any political scheme, was the real revolution.