Most people hitting the gym focus on the "show muscles." You know the ones—biceps, pecs, maybe the quads. But there is a group of muscles on the side of your hip that basically dictates whether you walk like a functional human or a folding lawn chair. We’re talking about the hip abductors. Specifically the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and the tensor fasciae latae (TFL). If you look at a hip abduction before and after photo, you might just see a slightly rounder hip or a more stable pelvic line. Honestly, though, the real transformation is invisible. It’s in the way your femur stops crashing into your knee joint.

It's about stability.

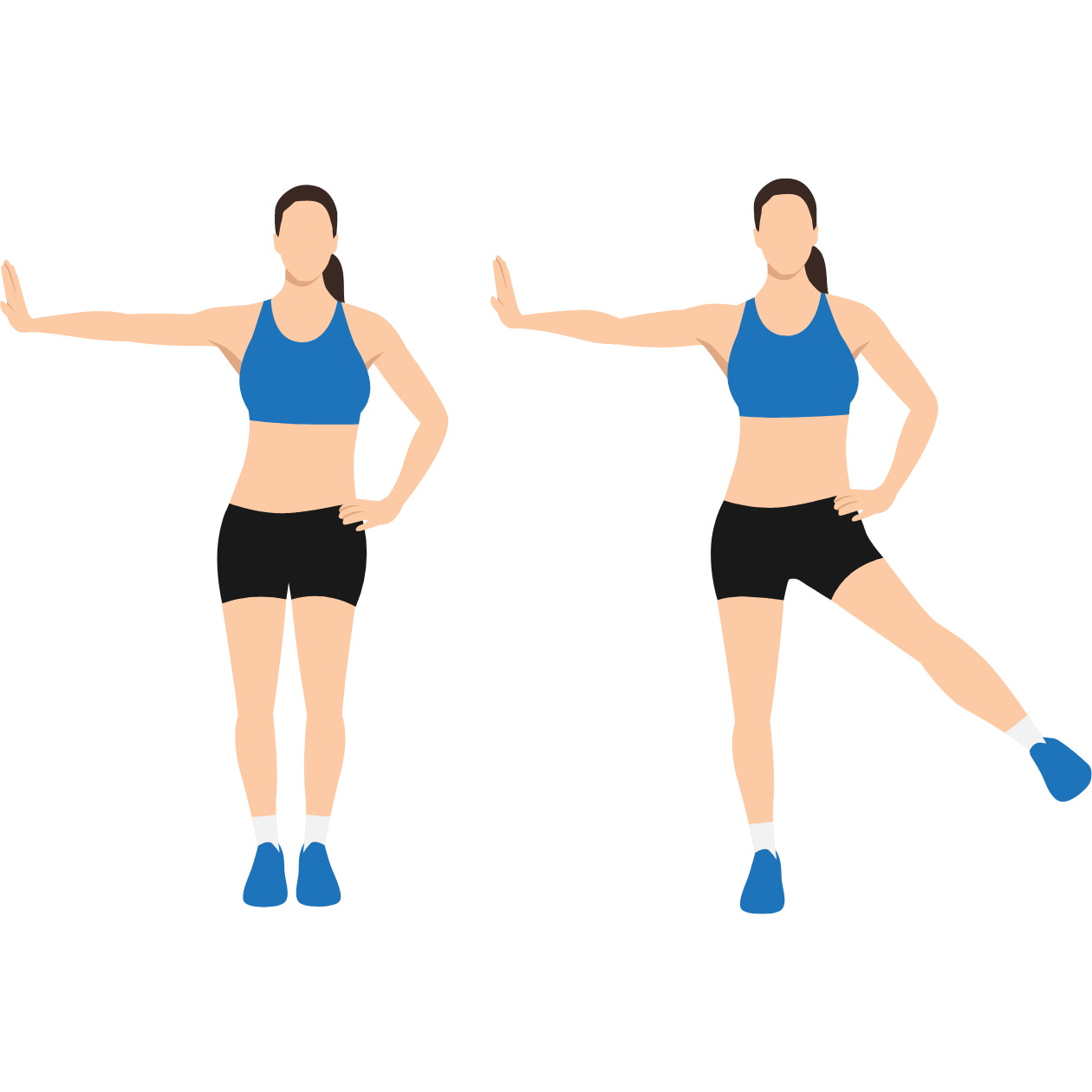

When we talk about hip abduction, we’re describing the movement of your leg away from the midline of your body. Think of a side-lying leg lift or that machine at the gym where you push your knees outward against resistance. It looks simple. It feels simple. But for runners, athletes, or anyone over 30 dealing with "random" lower back pain, this movement is the holy grail of injury prevention.

The Anatomy of a Hip Abduction Transformation

The "before" state for most people is a mess of compensations. If your abductors are weak, your brain doesn't just stop you from walking. Instead, it "borrows" strength from elsewhere. You’ll see the "Trendelenburg sign." This is a fancy clinical term for when your hip drops on the opposite side of your standing leg. It looks like a sassy strut, but it’s actually your pelvis failing to stay level because your glute medius is essentially asleep at the wheel.

Over time, this causes a kinetic chain reaction. Your knees cave inward—valgus collapse—which is the express lane to an ACL tear or chronic IT band syndrome. Your lower back (the quadratus lumborum) starts trying to lift your hips for you. That’s why your back hurts after a long walk. It’s not a back problem. It’s a hip abduction problem.

The "after" is where things get interesting. Strengthening these lateral muscles creates a "pelvic reset." In a hip abduction before and after clinical context, researchers look for improved "frontal plane stability." This means when you run or jump, your knees stay tracked over your toes. Your pelvis remains level. You stop leaking energy side-to-side and start moving forward with actual efficiency.

Real Science on the Lateral Line

Let's look at the numbers. A study published in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy (JOSPT) highlighted that runners with patellofemoral pain syndrome—basically "runner's knee"—showed significantly lower hip abductor strength than healthy controls. When they put these runners through a six-week hip strengthening protocol? The pain didn't just "lessen." In many cases, it vanished.

Why? Because the hip abductors control the femur.

If the hip is weak, the thigh bone rotates inward. This grinds the kneecap against the femoral groove. By fixing the hip abduction strength, you’re basically realigning the tracks for the train. It's mechanical.

What a Real Hip Abduction Before and After Looks Like

Visually, don't expect to look like a bodybuilder overnight. The glute medius is a relatively thin, fan-shaped muscle. It sits under the gluteus maximus. However, you will notice a change in "hip dip" prominence—though genetics plays a massive role there—and a much firmer side-glute profile.

The real changes?

- Balance: You can stand on one leg for a minute without wobbling like a Jenga tower.

- Running Mechanics: Your feet land quieter. You aren't "slapping" the pavement.

- Power: Your squat and deadlift numbers usually go up because your base is finally stable.

I remember talking to a physical therapist, Dr. Chris Powers, who has done extensive work on this at USC. He’s essentially argued that if you don't control the hip, you can’t control the knee. It’s that simple. Most people spend years stretching their "tight" IT bands, but the IT band isn't the problem. The weak hip that's letting the IT band get overstretched is the problem. Stop stretching. Start abducting.

The Tools of the Trade

You don't need a $5,000 machine. Honestly, a $10 pack of latex resistance bands is usually enough to start the process.

- Clamshells: They look like a 1980s aerobics move. They work. Focus on keeping your hips stacked; don't let your top hip roll backward.

- Side-Lying Leg Raises: Simple, but most people do them wrong. Keep your toe pointed slightly down or neutral. If you point your toe up, you’re just using your hip flexors.

- Monster Walks: Put a band around your ankles and shuffle sideways. You’ll feel a burn in the "side-butt" area within thirty seconds. That’s the glute medius screaming for help.

- Copenhagen Planks: This is the advanced version. It targets the adductors (the inside) too, creating a balanced "sleeve" of strength around the hip.

Common Pitfalls and Why You’re Not Seeing Progress

The biggest mistake? Overactive TFL. The Tensor Fasciae Latae is a small muscle on the front-side of your hip. It loves to take over for the glute medius. If you finish your hip abduction before and after workout and the front of your hip feels tight but your glutes feel nothing, you failed. You’re just reinforcing the bad patterns that caused the pain in the first place.

💡 You might also like: Is Ibuprofen or Tylenol Better for a Fever? What the Science Actually Says

You have to "find" the glute. Touch the side of your hip while you do the movement. Feel the muscle contract. If it’s not firming up, adjust your leg position. Usually, moving your leg slightly backwards (extension) during the abduction will help trigger the gluteal fibers instead of the TFL.

Another thing is volume. These are endurance muscles. They are "postural." They are meant to work all day while you walk. Doing three sets of ten once a week is a waste of time. You need frequency. Think high reps, short rests, and daily activation.

The Psychological Shift

There is something weirdly empowering about feeling stable on your feet. When your hips are "on," you feel taller. You feel more athletic. It’s a subtle shift in how you carry your weight. You stop feeling like you're "falling" into every step and start feeling like you're "driving" into the ground.

Actionable Steps for a Successful Transformation

If you're serious about seeing a real hip abduction before and after result, stop treating it as an afterthought.

- Audit Your Walk: Have a friend film you walking away from them. Does your hip drop? Do your feet turn out like a duck? These are your "before" markers.

- The 30-Day Glute Medius Challenge: Do 50 lateral band walks and 30 side-lying leg lifts every single morning. No exceptions. It takes four minutes.

- Isolate Before You Integrate: Don't just rely on squats. Squats are great, but the big muscles (glute max) often bully the smaller ones (glute med) into staying quiet. Isolate the abduction first, then go do your heavy lifts.

- Monitor Knee Tracking: When you do lunges or go down stairs, watch your kneecap. It should stay in line with your second toe. If it dives inward, your abductors aren't doing their job. Fix it in real-time.

Consistency here beats intensity. You aren't trying to win a weightlifting competition with your lateral hips. You're trying to build a structural foundation that keeps your joints from wearing out by age 50. Pay the tax now or pay the surgeon later. It’s really that simple. Focus on the quality of the squeeze, keep the TFL out of it, and watch how your "random" aches start to disappear as your hips finally learn to hold their own weight.