Walk into any arcade today or fire up a PS5, and you’re looking at the distant, high-tech descendants of a science project. Seriously. It wasn't built in a garage by a college dropout or a Silicon Valley billionaire. It was built in a nuclear research facility by a guy who helped invent the atomic bomb.

When William Higinbotham built Tennis for Two in 1958, he wasn't trying to start a multi-billion-dollar industry. Honestly, he was just bored with how dry science exhibitions were. He wanted to liven things up at the Brookhaven National Laboratory open house. He saw people walking past static displays of Geiger counters and blueprints, looking halfway to a nap. He figured, "Why not give them something to actually do?"

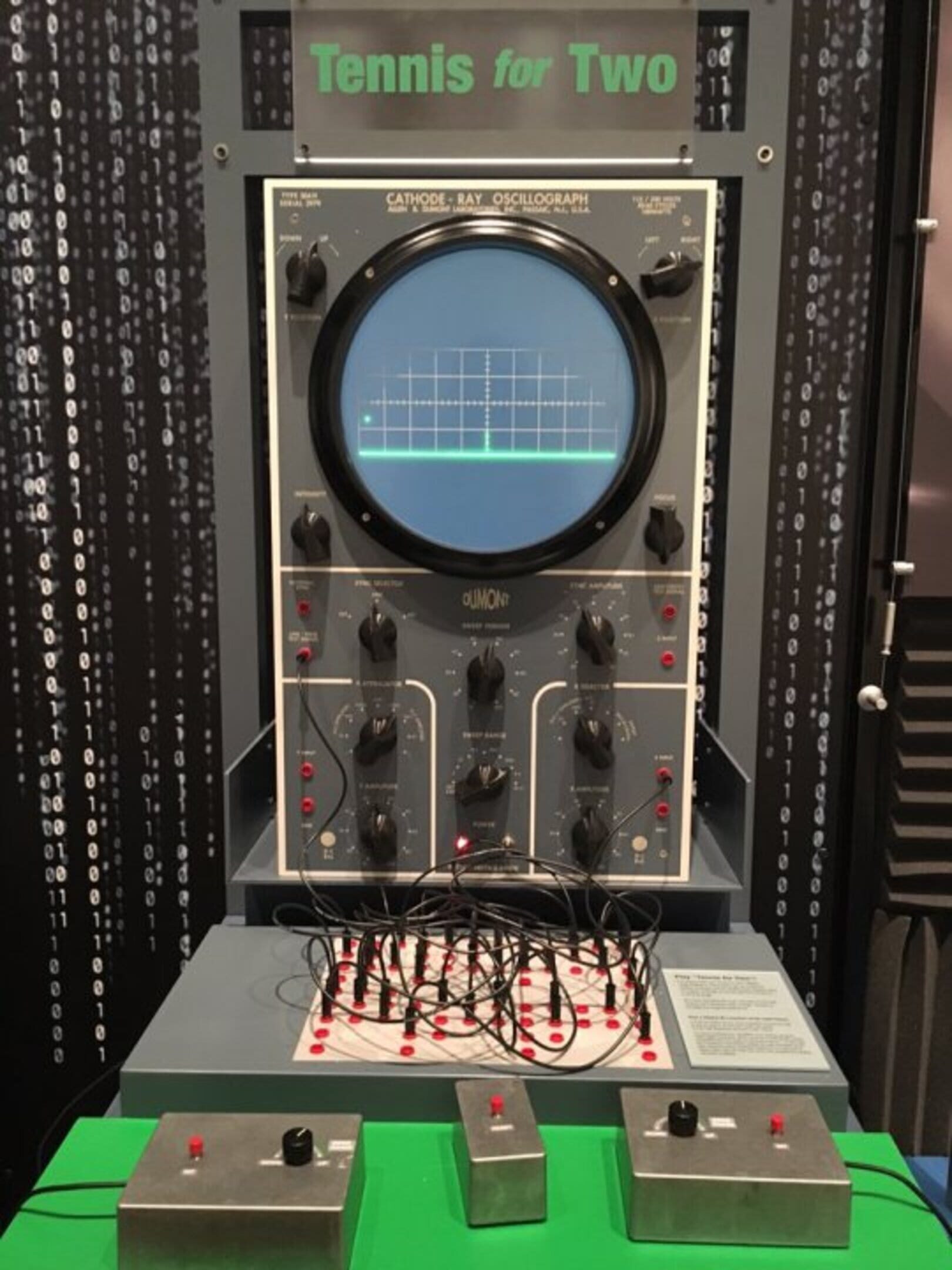

The result was a green glowing dot on a five-inch screen that changed everything.

The Manhattan Project Scientist Who Just Wanted to Have Fun

To understand why Tennis for Two is such a weird anomaly in history, you have to look at William Higinbotham himself. This wasn't a "gamer." The word didn't even exist. Higinbotham was a heavy-hitter physicist. During World War II, he was at Los Alamos, specifically heading up the electronics group. He was the guy who designed the timing circuits for the first atomic bomb.

Think about that. The guy who helped trigger the most destructive weapon in human history also gave us the first thing we ever "played" on a screen.

After the war, he felt a massive weight on his shoulders. He became a huge advocate for nuclear non-proliferation, helping found the Federation of American Scientists. By 1958, he was working at Brookhaven, and the annual visitors’ day was coming up. He noticed that the lab's analog computer—a Donner Model 30—could calculate missile trajectories. He realized that if a computer can track a missile, it can definitely track a tennis ball.

🔗 Read more: Why Sun and Moon Dress to Impress Styles Are Dominating the Runway Right Now

It took him about two hours to sketch the design. It took a technician named Robert Dvorak about three weeks to wire it all together.

How Tennis for Two Actually Worked (No, It Wasn't Digital)

If you saw the guts of Tennis for Two, you wouldn’t recognize it as a "game console." There was no CPU. No memory. No code.

Basically, the whole thing was an analog circuit. It used an oscilloscope—a tool scientists use to look at wave patterns—as the monitor. The "graphics" were just lines of light. One horizontal line for the ground, a vertical line for the net, and a bright dot for the ball.

The Original Controller

You've probably seen a PlayStation controller with its 15 buttons and dual sticks. Higinbotham’s controllers were a bit more... minimalist.

- A single knob: This controlled the angle of your return.

- A big button: This was the "hit" button.

You couldn't move your "racket" because there weren't any rackets. You just waited for the ball to get to your side and timed your button press. If you hit it right, the ball would arc over the net. The physics were surprisingly legit, too. Higinbotham programmed in wind resistance and gravity. In the 1959 version, he even added a switch so you could play on the Moon or Jupiter.

Gravity on the Moon? In 1959? That’s wild.

The Great "First Video Game" Debate

People argue about this constantly. Was Tennis for Two the first?

Some folks point to OXO, a tic-tac-toe game from 1952. Others mention the "Cathode-Ray Tube Amusement Device" from 1947. But here's the thing: OXO was a PhD project about human-computer interaction. The 1947 device was just a hardware overlay.

Tennis for Two was different because its only purpose was fun. It was the first time someone used a computer purely to make people smile.

👉 See also: How Much Storage Does Switch 2 Have: What Most People Get Wrong

However, technically, it might not be a "video" game. Most purists say a video game needs to output a video signal (like a TV). Tennis for Two used an X-Y plotter system on an oscilloscope. It’s a technicality that keeps historians up at night, but for most of us, it’s the clear ancestor of everything we play now.

Why It Was Forgotten for Decades

After the 1959 exhibition, the game was dismantled. The parts were recycled for other lab experiments. Higinbotham didn't even think to patent it. He thought it was just a neat little demo. He actually said later that he didn't think it was that big of a deal.

The world forgot about it until the late 1970s.

That’s when Magnavox started suing everyone. They held the patents for Ralph Baer's "Brown Box" (which became the Odyssey) and were claiming they invented the electronic game. Lawyers started digging. They found out about this guy at Brookhaven who had a working game 14 years before Pong. Higinbotham had to testify in court. Suddenly, this "forgotten" science project was the key evidence in a multi-million dollar legal war.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Devs

If you’re a fan of gaming history or a developer, there is actually a lot to learn from Higinbotham’s approach.

- Study Analog Physics: Modern games spend massive GPU power to simulate what Higinbotham did with vacuum tubes and resistors. Looking at analog recreations of the game (which Brookhaven sometimes puts on display) shows how "feel" is more important than "pixels."

- Visit the Source: If you’re ever in Long Island, the Brookhaven National Laboratory sometimes holds events where they bring out recreations. It’s worth seeing the green glow in person.

- Play the Simulators: There are several JavaScript and Flash-based (now emulated) versions of Tennis for Two online. Try playing one. You'll notice the timing is surprisingly difficult.

The story of William Higinbotham is a reminder that the best innovations usually come from a simple place: someone looking at a boring situation and deciding to make it fun. He didn't want to be the "Grandfather of Video Games"—he actually preferred to be remembered for his work on nuclear peace. But whether he liked it or not, that little green dot started a revolution.

To see the original schematics or learn more about the lab's current work, you can check out the official Brookhaven National Laboratory history page.

👉 See also: Finding a Real GameMT E6 Custom Firmware Download: Why It Is So Hard to Find

Keep an eye on retro-gaming exhibits at the Smithsonian as well; they’ve featured the game’s history prominently in their "Art of Video Games" collections. Exploring those exhibits is the best way to see the actual hardware that survived the era.