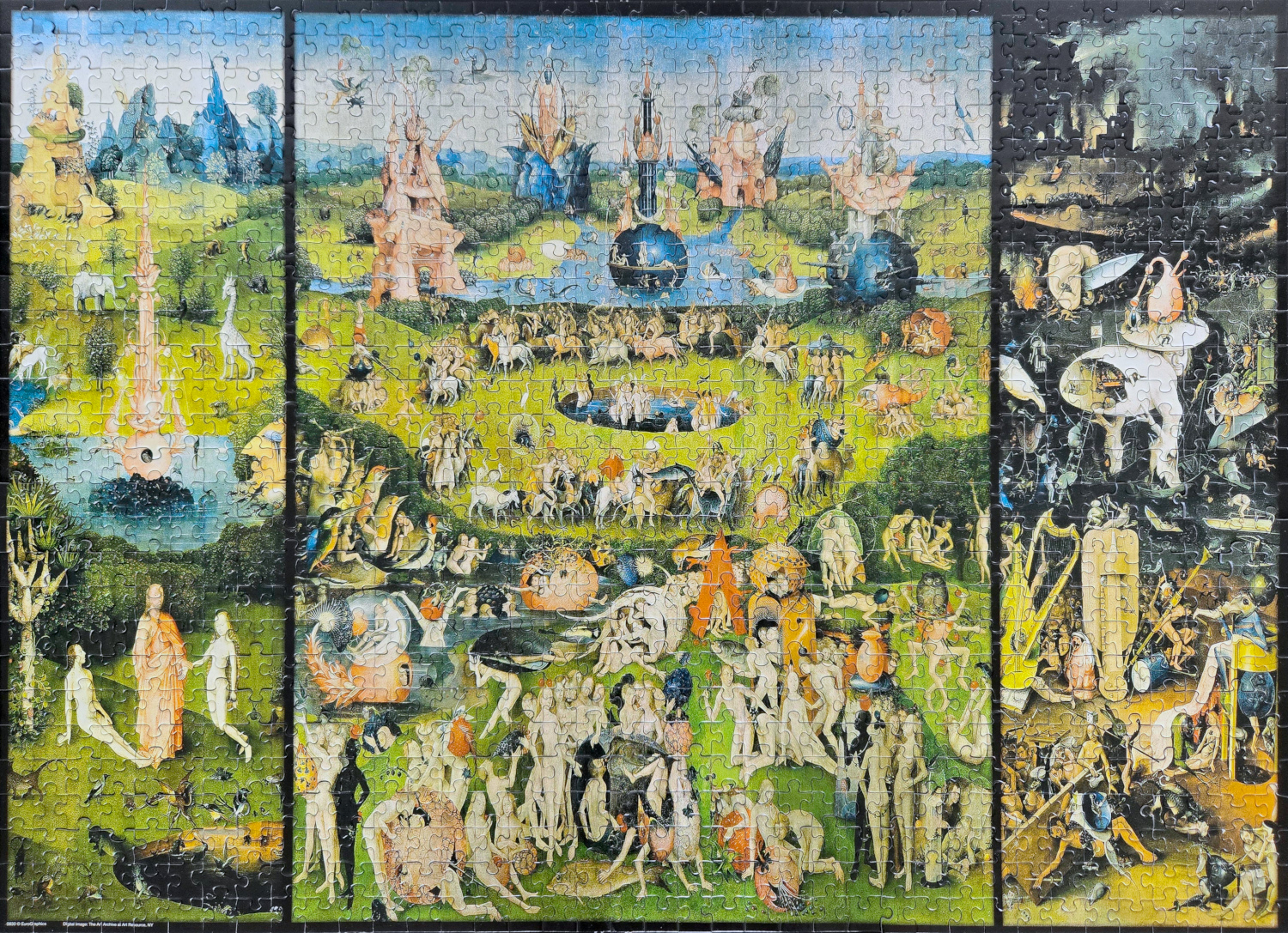

You’ve probably seen it on a tote bag or a Dr. Martens boot. Maybe you saw it in a textbook and squinted at the tiny, frantic figures. The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch is arguably the most famous triptych in the history of Western art, but it’s also the weirdest. It’s a 500-year-old fever dream that somehow feels more modern than a lot of contemporary surrealism.

Looking at it is overwhelming. Truly.

Most people see a chaotic mess of naked bodies, giant strawberries, and musical instruments being used as torture devices. But if you actually sit with it—really stare at the high-definition scans or stand in front of it at the Museo del Prado in Madrid—you start to realize that Bosch wasn't just "tripping" or being random. He was a meticulous, deeply religious moralist who was terrified of what humanity was becoming. Or, at least, that’s what the art historians think. Honestly? We don't actually know for sure. That's the beauty of it.

The Mystery of the Man Behind the Madness

Hieronymus Bosch is a ghost. We know he lived in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, a city in the Netherlands. We know he was part of a conservative religious group called the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady. We know he died in 1516.

That’s basically it.

There are no diaries. No manifestos explaining why he decided to paint a man with a bird's head eating people and then defecating them into a pit. Because we have so little biographical info, the Garden of Earthly Delights has become a Rorschach test for every generation that looks at it. In the 1960s, people thought he was a proto-hippie celebrating free love. In the 1920s, the Surrealists claimed him as their grandfather. In his own time, he was likely seen as a guy giving a very stern, very scary sermon about why you shouldn't be obsessed with sex and snacks.

Breaking Down the Three Panels (and the Closed One)

Most people forget the painting is actually a folding screen. When the shutters are closed, you see the world during creation—a translucent sphere with a flat earth inside, painted in drab greys (grisaille). It’s quiet. It’s lonely. It’s the "before" picture.

🔗 Read more: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

Then you open it. It's an explosion of color.

The Left Panel: The Setup

This is Eden. But it’s not the peaceful Eden you see in Sunday school. Sure, God is there introducing Eve to Adam, but look in the background. There’s a cat with a lizard in its mouth. There’s a weird, pink fountain that looks suspiciously like a biological organ or a piece of laboratory equipment. Even in paradise, Bosch is hinting that things are already kinda gross and predatory. Nature is "red in tooth and claw" before the Fall even happens.

The Center Panel: The Party

This is the Garden of Earthly Delights itself. It’s a massive landscape filled with hundreds of naked people doing... things. They’re hugging giant birds. They’re huddling inside translucent bubbles. They’re eating oversized fruit like their lives depend on it.

There is a huge debate about this panel. Is it a celebration of life? Or is it a "false paradise" showing people indulging in fleeting pleasures right before they go to hell? Given the right panel, the "false paradise" theory carries a lot of weight. Bosch uses strawberries everywhere. In the 1500s, strawberries were a symbol of something that tastes sweet for a second but rots quickly. It’s a metaphor for "short-term gains, long-term pains."

The Right Panel: The Aftermath

Then there's the "Musical Hell." This is the stuff of nightmares. You have the "Tree-Man," whose body is a broken eggshell and whose face is a self-portrait of Bosch (maybe). You have a rabbit carrying a bleeding corpse. You have a giant pair of ears sliced by a knife.

Bosch seems to have a specific grudge against music here. Instruments like harps and lutes are used to crucify and torture the damned. Why? Because in the late Middle Ages, secular music was often linked to idle behavior and "sinful" dancing. If you spent your life partying to the lute, you’re getting poked by a lute for eternity. It’s harsh. It’s vivid. It’s incredibly detailed.

💡 You might also like: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

Why Does It Look So "Alienesque"?

If you look at paintings from 1500, they usually look like... well, the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci was painting the Mona Lisa around the same time. While Leonardo was obsessed with soft shadows and perfect human anatomy, Bosch was busy inventing monsters that look like they belong in a Star Wars cantina.

His style is "North" vs "South." While the Italians were looking back at Greek statues for inspiration, Bosch was looking at the "drolleries" found in the margins of medieval manuscripts. He took those tiny, weird doodles of monsters and blew them up to a massive scale.

He didn't care about perfect perspective. He cared about narrative density.

The Most Famous Misconceptions

People love to say Bosch was on drugs. Ergotism—a fungus that grows on rye and causes hallucinations—was common back then. But historians like Hans Belting argue that the painting is way too organized and technically precise to be the result of a random trip. Every weird bird and strange plant is placed with intent.

Another big mistake is thinking this was an altarpiece for a church. Imagine this behind a priest during Mass. It would be a total distraction. It was actually commissioned by the House of Nassau for their palace in Brussels. It was a conversation piece. It was meant for rich, educated people to stand around with glasses of wine and argue about what the different symbols meant. It was the 16th-century version of a high-concept HBO show.

How to Actually "Read" the Painting Today

If you want to get the most out of The Garden of Earthly Delights, you have to stop looking at it as a single image. You have to read it like a comic book. Start from the top left and meander your way down and across.

📖 Related: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

- Look for the animals: Bosch was obsessed with birds. Kingfishers, mallards, and owls (which usually represented evil or trickery in his world).

- Check the scale: Notice how the humans are small, but the fruit and birds are huge. This inversion suggests that our desires (the fruit) have grown so big they’ve taken over our logic.

- Find the "Hidden" symbols: There’s a man with a flute stuck in his backside. There’s a pig wearing a nun’s veil trying to get a man to sign a legal document. It’s satirical. It’s biting.

The Legacy of the Garden

The influence here is infinite. You can see Bosch’s DNA in the films of Guillermo del Toro. You see it in the album art for Deep Purple or the fashion shows of Alexander McQueen.

Why? Because Bosch tapped into something universal: the anxiety of being human. We are caught between our highest aspirations (Eden) and our lowest impulses (Hell), stuck in a middle ground where we mostly just act like confused animals eating giant strawberries.

He captured the absurdity of existence before we even had a word for it.

Actionable Ways to Experience Bosch

If you can't fly to Madrid tomorrow, there are better ways to see this than a grainy Google Image search.

- Use the Bosch Garden official interactive site: There is a high-resolution project (often hosted by the Bosch Research and Conservation Project) that lets you zoom in until you can see the cracks in the paint. Do this on a big monitor.

- Read "Bosch" by Wilhelm Fraenger: While some of his theories are considered "out there" by modern standards (he thought Bosch was part of a secret sex cult), his analysis of the individual symbols is legendary.

- Watch "Hieronymus Bosch, Touched by the Devil": This documentary follows the curators at the Noordbrabants Museum as they try to secure the painting for an anniversary exhibition. It shows the sheer physical scale and the fragility of the wood panels.

- Visit the Museo del Prado virtually: They have an incredible collection of Bosch works, including The Haywain Triptych, which is like the "B-side" to the Garden of Earthly Delights.

Understanding Bosch isn't about "solving" the painting. There is no single answer. It’s about accepting that 500 years ago, a man saw the world as a beautiful, terrifying, hilarious, and doomed place—and he was right.