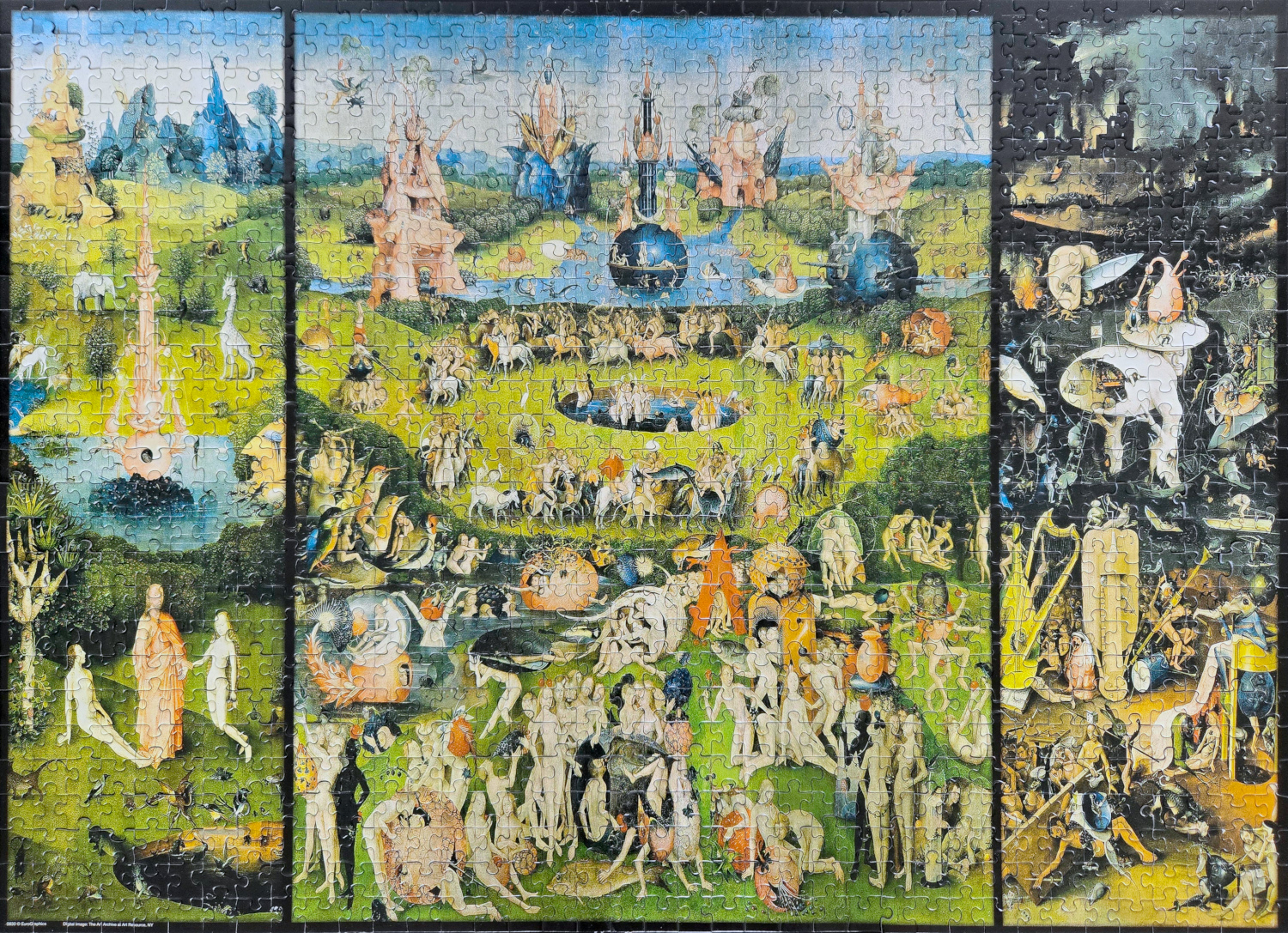

You’ve probably seen it on a tote bag or a Dr. Martens boot. Maybe you saw it in a textbook and squinted at the tiny, naked people cavorting with giant strawberries. The Garden of Earthly Delights is that kind of painting. It’s a three-panel trip into the subconscious of a man who died over 500 years ago, yet it feels more modern than almost anything in the Prado Museum. Hieronymus Bosch wasn't just an artist; he was a world-builder who seemed to have access to a very specific, very dark set of hallucinations.

It’s weird.

Actually, weird doesn't cover it. It’s a masterpiece of the "Early Netherlandish" period, painted somewhere between 1490 and 1510. We don't even have an exact date because Bosch didn't bother to date his work. He just dropped this massive triptych on the world and left us to figure out why there’s a man with a bird flute stuck in his posterior.

What’s Actually Happening in These Panels?

Most people think of this as a "heaven and hell" painting. That’s a bit of a simplification. When the shutters are closed, you see the world during creation—basically a grey, translucent sphere. But when you crack it open? Color. Madness. Chaos.

The left panel is technically Paradise. You see God (looking surprisingly young) introducing Eve to Adam. But even here, Bosch is hinting that things are already going off the rails. Look closely at the background. There’s a cat walking away with a mouse in its mouth. There’s a strange, pink fountain that looks like it was designed by an alien architect. Even in "perfection," Bosch saw the teeth and claws of nature.

Then you hit the center. This is the The Garden of Earthly Delights itself. It’s a sprawling, sun-drenched landscape filled with hundreds of naked figures. They are eating giant cherries, hugging owls, and lounging in transparent bubbles. For a long time, historians argued about what this meant. Was it a celebration of free love? A secret manual for a heretical sect called the Adamites?

Probably not.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Most modern scholars, like Reindert Falkenburg, suggest it’s actually a warning. It’s a false paradise. These people are indulging in "transitory" pleasures—things that taste good for a second but don't last. The giant strawberries represent the fleeting sweetness of sin. It looks like a party, but it’s really a waiting room for the third panel.

The Music from Hell

The right panel is where Bosch really lets loose. This is the "Musical Hell."

Why music? Because in the 1500s, loud, secular music was often associated with loose morals. Bosch takes that literally. You see a man crucified on a lute. Another is trapped inside a giant drum. There is even a fragment of sheet music tattooed onto a sinner's buttocks.

A few years ago, a student named Amelia Hamrick actually transcribed that "butt music" and performed it. It’s a haunting, somber melody that sounds exactly like what you’d expect to hear in a Flemish nightmare.

And then there’s the "Prince of Hell." He’s a giant bird-headed creature sitting on a high chair (which is actually a latrine), swallowing humans whole and excreting them into a dark pit. It’s visceral. It’s gross. It’s honestly kind of funny if you have a dark enough sense of humor. Bosch wasn't just trying to scare people; he was mocking human folly. He was the original satirist.

Why Does It Look So Different From Other Art?

If you look at what else was happening around 1500, you have the Italian Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci was painting the Mona Lisa. Everything was about perspective, anatomy, and classical beauty.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

Bosch didn't care about that.

He stayed in his hometown of 's-Hertogenbosch. He wasn't interested in making people look like Greek gods. He wanted to show the internal state of the human soul. His figures are thin, pale, and almost rubbery. They don't have the "weight" of a Michelangelo figure. This gives the whole painting a dreamlike—or nightmare-like—quality.

His technique was also surprisingly fast. While other artists were layering thin glazes over months, Bosch used alla prima techniques in some areas, laying down wet paint on wet paint. You can see the energy in the brushstrokes. It’s frantic. It matches the subject matter.

The Mystery of the Patron

Who would buy this? You couldn't exactly hang a giant painting of a "man-tree" in a local parish church.

For a long time, people thought it was an altarpiece. Now, we're pretty sure it was commissioned by the House of Nassau for their palace in Brussels. It was a conversation piece. Imagine being a 16th-century aristocrat, having a few drinks, and standing in front of this thing with your friends. You’d spend hours pointing out the weird creatures. It was the high-brow version of a "Where's Waldo" book, but with more eternal damnation.

Because it was in a private palace, Bosch could get away with imagery that would have been censored in a cathedral. He was playing to an elite, educated audience who understood his complex metaphors and dark jokes.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

The Modern Obsession

Surrealists like Salvador Dalí loved Bosch. They saw him as a spiritual ancestor. When you look at the "Tree-Man" in the hell panel—a hollowed-out torso with human legs that look like rotting tree trunks—it’s pure surrealism.

But it’s more than just "cool" imagery. The Garden of Earthly Delights resonates today because it captures the anxiety of being human. We still struggle with the same things: the pursuit of pleasure, the fear of the future, and the nagging feeling that the world is a bit broken.

Bosch reminds us that humanity hasn't changed that much. We’re still the same people eating the giant strawberries, hoping the party never ends, even as the music starts to sound a bit ominous.

How to Actually "See" the Painting Today

If you want to experience this properly, don't just look at a JPEG on your phone. The scale is massive. It’s over seven feet tall.

- Visit the Prado: It lives in Madrid. The room is usually crowded, but if you go right when the museum opens, you can stand inches away from it. The detail is staggering. You can see individual eyelashes.

- Use the "Bosch Project" Website: If you can't get to Spain, the Bosch Research and Conservation Project has ultra-high-resolution scans. You can zoom in until a single bird's head fills your entire screen. It’s the only way to see the "hidden" details, like the tiny figures drowning in the background of the central panel.

- Ignore the "Drug" Theories: People love to say Bosch was on ergot or magic mushrooms. There is zero evidence for this. He was a member of the "Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady," a very conservative religious group. His "trippiness" came from a deep knowledge of medieval folklore, bestiaries, and religious texts. Real imagination is much more interesting than a drug trip anyway.

- Follow the Eyes: Notice how almost nobody in the center panel is looking at you. They are all obsessed with their own little world. Then look at the "Tree-Man" in Hell. He is looking directly at the viewer. He’s inviting you in. Or maybe he’s warning you.

The painting doesn't offer easy answers. It’s a mirror. What you see in it says more about you than it does about Bosch. If you see beauty and playfulness, maybe you're an optimist. If you see a terrifying warning about the end of the world, well, you're in good company with most of the art historians from the last five centuries.

Take a moment to look at the "Music Hell" panel again. Find the sheet music on the sinner's backside. Try to hum it. Once you hear the "butt song," you'll never look at Northern Renaissance art the same way again. It’s the perfect reminder that even in the deepest pits of darkness, Bosch found room for a little bit of absurd, human melody.

To get the most out of your next museum trip or art history deep dive, start by looking for the "inversions." Bosch loved taking things that should be small (birds, berries) and making them huge, while making things that should be important (the figures of Adam and Eve) feel small and vulnerable. This flip in scale is exactly why the painting feels so disorienting and modern. Keep an eye out for the glass globes and cylinders scattered throughout—they were symbols of alchemy in the 1500s, representing the fragile and volatile nature of life itself.