Henry Miller was a mess. By the time he sat down to write Tropic of Capricorn, he wasn't trying to be a "man of letters" or some refined novelist winning awards in a tuxedo. He was a guy who had been chewed up and spat out by the machinery of 1920s Brooklyn and Manhattan. He was broke. He was desperate. Honestly, he was kind of a jerk to almost everyone in his life. But that desperation is exactly why the book still vibrates with this weird, electric energy today.

If Tropic of Cancer was about Miller finding his soul while starving in Paris, then Tropic of Capricorn is the prequel that explains how he lost it in the first place. It’s a chaotic, filthy, and deeply philosophical look at what it means to be a human being trapped in a job you hate, in a city that doesn't care if you live or die.

The Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company: A Bureaucratic Hell

The heart of the book is Miller’s fictionalized version of his time at Western Union, which he renames the "Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company." It’s one of the most brutal depictions of corporate life ever put to paper. Miller served as a personnel manager, and his job was basically to hire and fire a revolving door of "messenger boys"—the desperate, the poor, the immigrants, and the outcasts of New York City.

He describes the office as a slaughterhouse for the human spirit.

You’ve probably felt that Sunday night dread before a work week? Miller turns that feeling into a 300-page scream. He wasn't just complaining about long hours or low pay; he was attacking the very idea that a person should spend their limited time on earth serving a machine. He saw the modern city as a graveyard where people walked around thinking they were alive, but they were actually just gears in a giant, uncaring clock. It’s bleak. It's funny. It's also incredibly relatable if you’ve ever sat in a cubicle wondering how your life ended up this way.

Why the 1939 Ban Actually Mattered

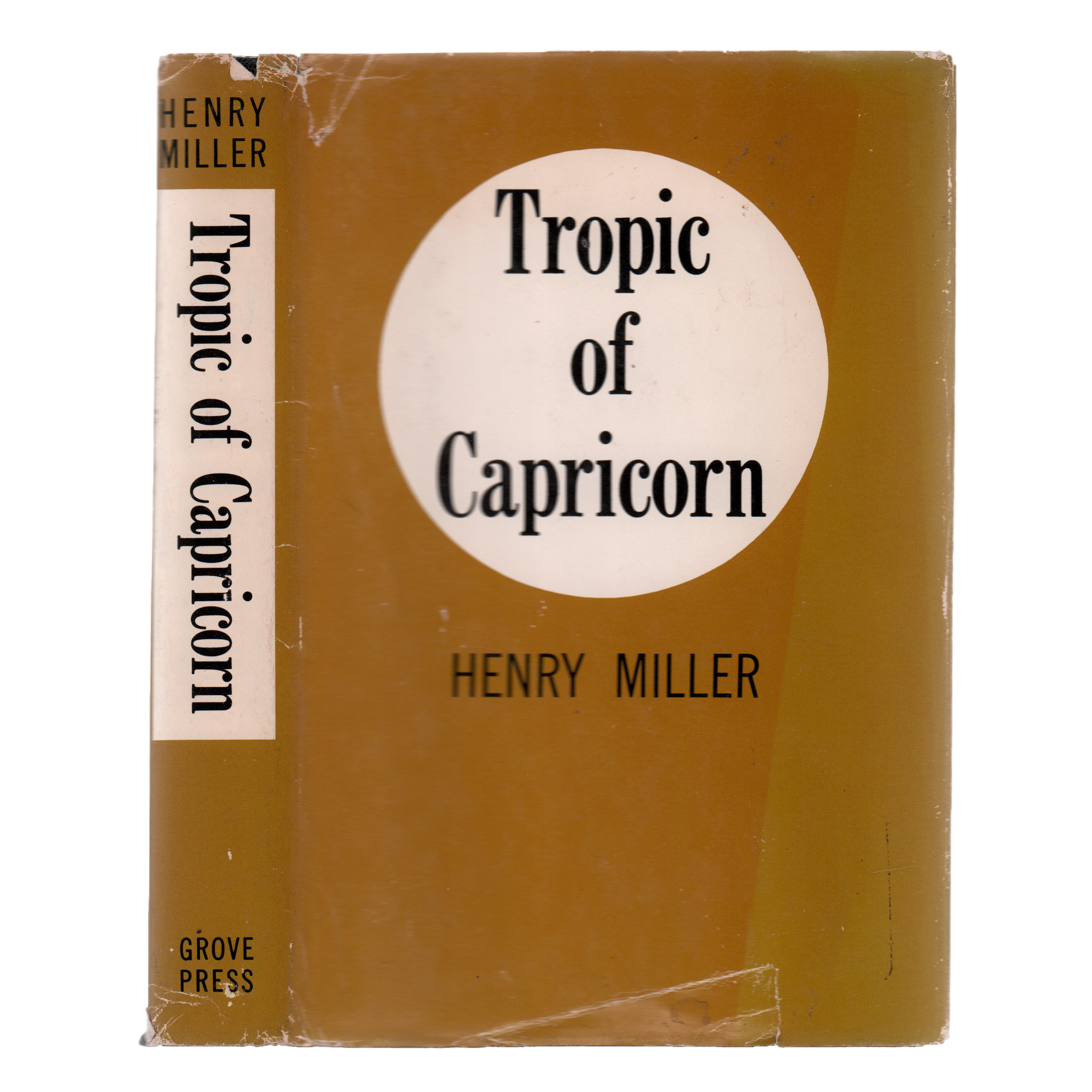

When Tropic of Capricorn was published in Paris in 1939 by Obelisk Press, it was immediately banned in the United States and Great Britain. For nearly thirty years, you couldn't legally buy this book in America. People had to smuggle copies in their suitcases like they were carrying contraband drugs.

Why?

💡 You might also like: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

The obvious answer is the sex. Miller writes about sex with a bluntness that shocked the 1930s world. He doesn't use metaphors or flowery language. He’s graphic, often uncomfortably so. But the "obscenity" wasn't just about the physical acts; it was about his refusal to be polite. The U.S. government, through the Customs Bureau, viewed the book as "dirt for dirt's sake."

But they were wrong.

The real "danger" of Miller wasn't the smut. It was the total anarchy of his thought. He was telling people that the American Dream was a scam. He was saying that the family structure, the church, and the government were all just different ways of keeping people bored and obedient. That’s way more threatening to a society than a few dirty words. When the ban was finally lifted in the 1960s following the landmark Supreme Court battles involving Tropic of Cancer, it didn't just change literature—it changed the legal definition of free speech in the West.

The Chaos of the Narrative

Don't expect a neat plot. If you want a story with a beginning, middle, and end, go read a thriller. Miller doesn't do that. Tropic of Capricorn jumps around like a fever dream. One minute he’s describing a gritty encounter in a basement apartment, and the next, he’s off on a ten-page rant about the nature of the universe or the spiritual death of the West.

He uses a "stream of consciousness" style, but it’s more aggressive than Joyce or Woolf. It’s more like a guy at a bar grabbing your collar and refusing to let go until he’s told you everything he’s ever thought.

- He explores his childhood in Brooklyn.

- He dissects his toxic relationship with his wife (called "Mona" in the books, based on June Mansfield).

- He talks about the "Land of Fuck"—his name for the frantic, hollow sexual landscape of the city.

- He wanders into surrealist territory where the city streets literally start to melt.

It’s exhausting. It’s also brilliant. Miller was trying to capture the "total life" of a man, which includes the boring bits, the gross bits, and the moments of sudden, blinding beauty.

📖 Related: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

The Controversy: Miller’s Blind Spots

We have to be real here: reading Tropic of Capricorn in the 2020s is a complicated experience. Miller was a product of his time, and he had some massive blind spots. His depictions of women and various ethnic groups in New York are often problematic, to say the least. He can be misogynistic. He can be prejudiced.

Critics like Kate Millett famously took Miller to task in the 1970s, arguing that his work reduced women to mere objects for his own self-discovery. She wasn't wrong.

However, ignoring the book because it’s "problematic" means missing out on one of the most honest psychological portraits of a frustrated man ever written. Miller isn't trying to be a hero. He’s showing you the warts, the ugliness, and the jagged edges of his own mind. He’s the original "unreliable narrator" because he’s too busy being himself to care if you like him or not.

The Influence on Modern Culture

Without Tropic of Capricorn, you don't get Jack Kerouac. You don't get Charles Bukowski. You don't get Hunter S. Thompson.

Miller paved the way for the "confessional" style of writing. He proved that you could write about your own life—no matter how messy or "unimportant"—and make it epic. He turned the "nobody" into a philosopher-king. The Beat Generation owed everything to him. They saw him as a grandfather figure who had survived the "air-conditioned nightmare" of America and lived to tell the tale.

Even today, you can see his influence in "auto-fiction" writers like Karl Ove Knausgård. That obsession with the minute details of daily life, mixed with grand philosophical inquiries? That’s pure Miller.

👉 See also: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

How to Read It Without Getting Lost

If you’re picking up the book for the first time, don't try to "understand" it in a traditional way.

First, ignore the structure. If you get bored during one of his long philosophical tangents, just keep skimming until you hit the prose again. The rhythm is what matters.

Second, remember the context. This is a book about a man trying to find a reason to live in a world that feels dead.

Third, pay attention to the descriptions of New York. Nobody writes about the grit of the city quite like Miller. He makes the pavement feel alive. He makes the noise of the elevated trains sound like music.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If Miller’s work teaches us anything, it’s that the "system" hasn't changed as much as we think. We still struggle with the balance between making a living and actually having a life.

- Audit your "Cosmodemonic" moments. Identify the parts of your daily routine that feel soul-crushing and mechanical. Miller’s solution was to walk away and write; yours might be different, but recognition is the first step.

- Practice radical honesty in your own expression. Miller’s power came from his willingness to say the things people usually keep hidden. You don't have to publish a banned book, but finding a space—a journal, a hobby, a conversation—to be completely unfiltered is vital for mental health.

- Explore the geography of your own history. Miller used his childhood in Brooklyn to understand his adulthood. Mapping out the places that shaped your "inner landscape" can provide clarity on why you view the world the way you do now.

- Read the contemporaries. To get the full picture, pair Miller with Anaïs Nin’s diaries from the same period. It provides a fascinating, different perspective on the same events and people.

Henry Miller eventually left New York for Big Sur, California, where he lived out his days as a sort of Zen-like sage, painting watercolors and writing about peace. But he had to go through the "Capricorn" phase first. He had to face the monster of the city and the monster of himself. That’s why the book remains a rite of passage for anyone who feels like they’re stuck in the machinery. It’s a roadmap for how to explode your life and start over.