You know that specific kind of panic? It’s 11:15 PM on a Tuesday. You’re staring at a grid that looks like a digital wasteland of empty white squares and one very stubborn "rebus" you can't quite crack. We've all been there. Getting the New York Times crossword solved isn't just about trivia; it’s about that dopamine hit when the golden sparkles finally dance across your screen.

But honestly, the culture around solving has changed. It used to be a lonely battle against a folded piece of newsprint and a leaking ballpoint pen. Now? It’s a global race. Between the Wordle-ification of our daily habits and the rise of competitive "speed-solving" on platforms like Twitch, the way we approach the Gray Lady’s puzzle has shifted from a casual hobby to a genuine mental sport.

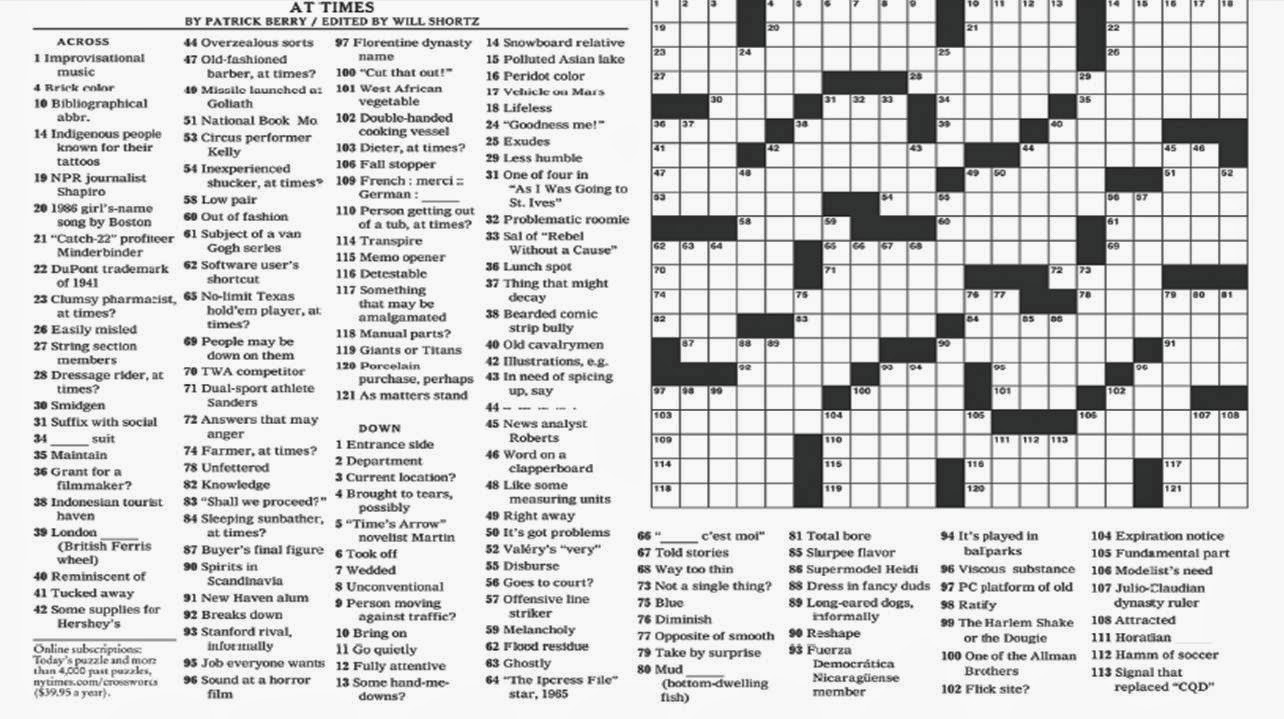

The Secret Architecture of the NYT Grid

Most people think the difficulty is just about how obscure the words are. That's a rookie mistake. Will Shortz, the long-time editor, and his team—including folks like Sam Ezersky and Wyna Liu—don’t just throw hard words at you. They use "tricky" cluing. A Friday puzzle might have a clue like "Lead-in to a second?" Most people think about time. They think about minutes. Nope. It’s "Milli," as in millisecond.

That’s the genius of it.

The progression of the week is a legendary piece of gaming design. Mondays are the "confidence boosters." They're the warm-up lap. By the time you hit Thursday, the grid literally starts breaking its own rules. You get "rebuses" where multiple letters cram into a single square, or "mirror" puzzles where the answers read backward. If you’re looking for the New York Times crossword solved on a Thursday, you aren't just looking for words; you're looking for the gimmick. Without the gimmick, the grid is unsolvable.

Why We Crave the Answer Key

There’s a weird guilt associated with looking up an answer. Is it cheating? Maybe. But in the world of modern "cruciverbalism," we call it "learning by osmosis."

If you're stuck on a clue about a 1940s jazz singer or an obscure river in central Europe, staring at it for three hours won't magically put that information into your brain. Looking up the solution—seeing that New York Times crossword solved—actually builds your mental database for the next time. The NYT has a "house style." They love certain words. If you see "ETUI" (a small needle case) or "ORLOP" (the lowest deck of a ship), you’re not seeing them because they’re common in daily life. You're seeing them because they have great vowel-to-consonant ratios that help constructors get out of tight corners.

🔗 Read more: Venom in Spider-Man 2: Why This Version of the Symbiote Actually Works

The Rise of the "Spoiler" Community

The internet has turned solving into a communal event. Sites like Rex Parker’s blog or the Reddit r/crossword community are basically the digital watercoolers of the puzzle world. They don't just give you the answers; they vent. They complain about "crosswordese"—those tired words like "AREA" or "ERIE" that appear way too often.

They also track "difficulty ratings." Did you know that some Saturdays are statistically harder than others based on the average solve time of thousands of users? It's true. The data is out there. People treat their "streak"—the number of consecutive days they've finished the puzzle without help—with a reverence usually reserved for religious icons.

The Psychology of the "Aha!" Moment

Brain science is actually pretty cool here. When you finally get the New York Times crossword solved, your brain releases a burst of dopamine. It’s the "Incomplete Task" phenomenon. Our brains hate open loops. An empty crossword grid is a massive open loop that creates a mild state of tension.

Solving it isn't just about being smart. It’s about relief.

- Pattern Recognition: Your brain is scanning for familiar letter strings (like -ING or -TION).

- Lateral Thinking: You have to ignore the primary meaning of a word and find the punny one.

- Memory Retrieval: Digging out that one random fact you learned in 8th-grade geography.

Sometimes, the frustration is the point. If it were easy, it wouldn't be the New York Times. It would be a word search from a diner placemat. The difficulty is the product.

Common Pitfalls That Stop Your Solve

Usually, when someone can't get the puzzle finished, it’s because of "mental anchoring." You’re so sure a 4-letter word for "Jump" is LEAP that you refuse to see it could be HOPS or OMIT (as in "jump over").

💡 You might also like: The Borderlands 4 Vex Build That Actually Works Without All the Grind

- Trust the Crosses: If a word feels wrong, it probably is. Delete it. Start over.

- Look for the Question Mark: If a clue ends in a question mark, it’s a pun. Always.

- The Rebus Factor: On Thursdays, if a word simply doesn't fit, try putting "T-H-E" or "C-A-T" in one single box. It sounds crazy until you do it.

I've seen people give up on a Saturday because they didn't know a specific name. But here’s the thing: you don't need to know the name. You need to know the words around the name. The "crosses" are your best friends.

The Ethics of the "Auto-Check" Feature

The NYT app has a feature called "Auto-Check." It marks your wrong letters in red immediately. Some purists think this is the end of civilization. Others think it’s a vital tool for accessibility.

Honestly? Who cares.

The goal is to engage your brain. If using a hint or seeing the New York Times crossword solved helps you understand the construction of the puzzle, you’re becoming a better solver. You're training your eyes to see the patterns. Eventually, you'll find you need the hints less and less.

How to Get Better (Without Just Cheating)

If you want to reach that elite level where you’re finishing Saturdays in under 20 minutes, you have to study. Not textbooks, but the puzzles themselves.

Keep a "notebook of shame." Every time you have to look up an answer, write it down. You'll notice that the same 50-100 words keep popping up because they make the geometry of the grid work. Words like "ALEE," "ETNA," and "IDEE."

📖 Related: Teenager Playing Video Games: What Most Parents Get Wrong About the Screen Time Debate

Also, learn your Greek and Roman mythology. The NYT loves a good Juno or Zeus reference. And birds. Why are there so many clues about ERETS or ERNES? Because they’re full of vowels.

The Future of the Solve

We’re moving into an era where AI can solve these puzzles in seconds. But that hasn't killed the hobby. If anything, it’s made the human element more valuable. We don't solve because we need the information; we solve because we want to see if we can outthink the human who built the cage.

Every puzzle is a conversation between the constructor (the person who built it) and the solver. When you see the New York Times crossword solved on your screen, you’ve basically just won an argument with a very smart stranger.

Your Practical Solve Strategy

To move from a casual solver to a pro, stop treating the clues as literal definitions. Start treating them as riddles.

- Step 1: Fill in all the "fill-in-the-blank" clues first. They are objectively the easiest.

- Step 2: Scan for plurals. If the clue is plural, the answer usually ends in 'S'. Put the 'S' in the grid even if you don't know the word yet.

- Step 3: If you’re truly stuck, walk away for twenty minutes. Your subconscious mind will keep working on the patterns. You’ll come back and "see" an answer that was invisible before.

- Step 4: Use a reliable "word-checker" only as a last resort to keep your momentum. Stagnation is the enemy of the streak.

The real "solve" isn't just filling the boxes; it's the mental flexibility you gain along the way. Keep your streak alive, but don't let it stress you out. It’s just a game, after all. A very, very addictive game.