The Gulf of Mexico isn't just a big, stagnant bowl of salt water sitting under the humid sun. If you’ve ever stood on a beach in Destin or Galveston and wondered why the water is crystal clear one day and murky the next, you’re looking at the visible signature of a massive, liquid engine. Gulf of Mexico currents are the invisible hands shaping everything from the intensity of Category 5 hurricanes to the price of your shrimp cocktail.

It’s easy to think of the ocean as just moving back and forth with the tides. But the Gulf is different. It’s a pressurized system. It’s basically a massive hydraulic machine fed by the Caribbean and drained by the Atlantic. If you want to understand why the weather in the UK is habitable or why oil spills behave so unpredictably, you have to look at the Loop Current.

The Loop Current: The Heartbeat of the Gulf

Most of the water in the Gulf of Mexico enters through the Yucatan Channel. It’s a narrow squeeze between Mexico and Cuba. Once that water pushes through, it doesn't just spread out evenly. It forms what oceanographers call the Loop Current.

This current is a warm, deep, and fast-moving ribbon of water. It travels north into the Gulf, then loops around clockwise, heading back south to exit through the Florida Straits. Think of it like a garden hose turned on full blast, pointed into a bucket. Sometimes the hose stays straight. Sometimes it whips around. When the Loop Current pushes far north—sometimes reaching almost to the Mississippi River Delta—it brings incredibly warm, tropical water into the northern Gulf.

This matters for one big reason: Heat.

Water holds energy. The Loop Current carries a massive amount of it. When a hurricane crosses over the "warm core" of this current, it’s like throwing gasoline on a fire. We saw this with Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita. These storms didn't just stay strong; they exploded in intensity because they tapped into the deep reservoir of thermal energy provided by these specific Gulf of Mexico currents. Most of the Gulf is shallow, and hurricanes usually "self-limit" by churning up cold water from the depths. But the Loop Current is warm hundreds of feet down. There is no cold water to churn up. The storm just keeps feeding.

When the Loop Breaks: Eddies and Rings

The Loop Current isn't a static line on a map. It’s moody. Every six to eleven months, the northern part of the loop gets too long and unstable. It eventually pinches off.

🔗 Read more: Why the Map of Colorado USA Is Way More Complicated Than a Simple Rectangle

Imagine a rubber band being stretched until a piece snaps off and forms a circle. In the Gulf, we call these "Eddies" or "Rings." Specifically, these are "Anticyclonic Eddies." They are giant, swirling whirlpools of warm water that drift slowly to the west.

- LME (Loop Current Eddies): These can be 200 miles wide.

- They rotate clockwise.

- They trap blue, clear Caribbean water inside them, which is why you’ll sometimes find tropical fish way off the coast of Texas.

- They can persist for months, slowly migrating toward the Mexican or Texan coastline before finally dissipating.

But there’s a flip side. Between these warm rings, you get smaller, counter-clockwise swirls called "Cold-Core Eddies." These are actually more important for fishing. While the warm Loop Current is a "biological desert" because it lacks nutrients, the cold-core eddies pull nutrient-rich water up from the bottom. This process, called upwelling, kicks off a plankton bloom. If you find a cold-core eddy, you find the tuna. It’s that simple.

Surface Drift and the Local Chaos

While the Loop Current handles the big-picture plumbing, the surface currents are what you actually feel when you’re swimming or boating. These are mostly driven by wind. In the summer, the prevailing winds from the southeast push water toward the shore. In the winter, "Northers" push it back out.

You've probably heard of rip currents. People often confuse these with "undertow," but they are totally different. A rip current is a narrow channel of water moving away from the shore. They happen when waves break strongly in some areas but not others. The water needs a way to get back out to sea. It finds a low point in the sandbar and rushes through like a river.

If you get caught in one, don't fight it. You’ll lose. Just swim parallel to the beach.

The Gulf of Mexico currents along the coast also create what’s known as "longshore drift." This is why beaches are constantly eroding in one spot and growing in another. On the Florida Panhandle, the sand is almost pure quartz, washed down from the Appalachian Mountains over millions of years. The currents move that sand from east to west, acting like a giant conveyor belt.

💡 You might also like: Bryce Canyon National Park: What People Actually Get Wrong About the Hoodoos

Why the Deep Water is a Different Beast

If you go a mile down, the story changes. The deep Gulf is dark, cold, and under immense pressure. Up until the last few decades, we thought the deep water was pretty still. We were wrong.

Deep-water currents in the Gulf are influenced by the topography of the sea floor—canyons, escarpments, and salt domes. There are "Topographic Rossby Waves" that move along the bottom. For the oil and gas industry, these are a nightmare. They can cause "vortex-induced vibrations" in the long pipes (risers) that connect a wellhead on the seafloor to a platform on the surface. If the current hits those pipes just right, they start to hum and vibrate until the metal fatigues and snaps.

Researchers like those at the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) spend millions of dollars mapping these deep currents. They use Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers (ADCPs) to "ping" the water and measure how fast it's moving at different depths. It’s a high-stakes game of physics.

The Human Element: Pollution and Dead Zones

We can’t talk about Gulf of Mexico currents without mentioning the Mississippi River. It’s the elephant in the room. The river dumps a massive amount of freshwater, nitrogen, and phosphorus into the Gulf.

Because freshwater is lighter than saltwater, it floats on top. This creates a "stratified" layer. The nutrients feed massive algae blooms. When the algae dies, it sinks and decomposes, a process that uses up all the oxygen in the water. This creates the "Dead Zone."

The currents determine where that dead zone goes. Usually, the prevailing currents push that low-oxygen water west toward the Louisiana and Texas coasts. Some years, it’s the size of New Jersey. If the currents shifted and pushed that water east, the tourism industry in Florida would see a total collapse of their local fisheries. It’s a delicate, albeit messy, balance.

📖 Related: Getting to Burning Man: What You Actually Need to Know About the Journey

The Global Connection

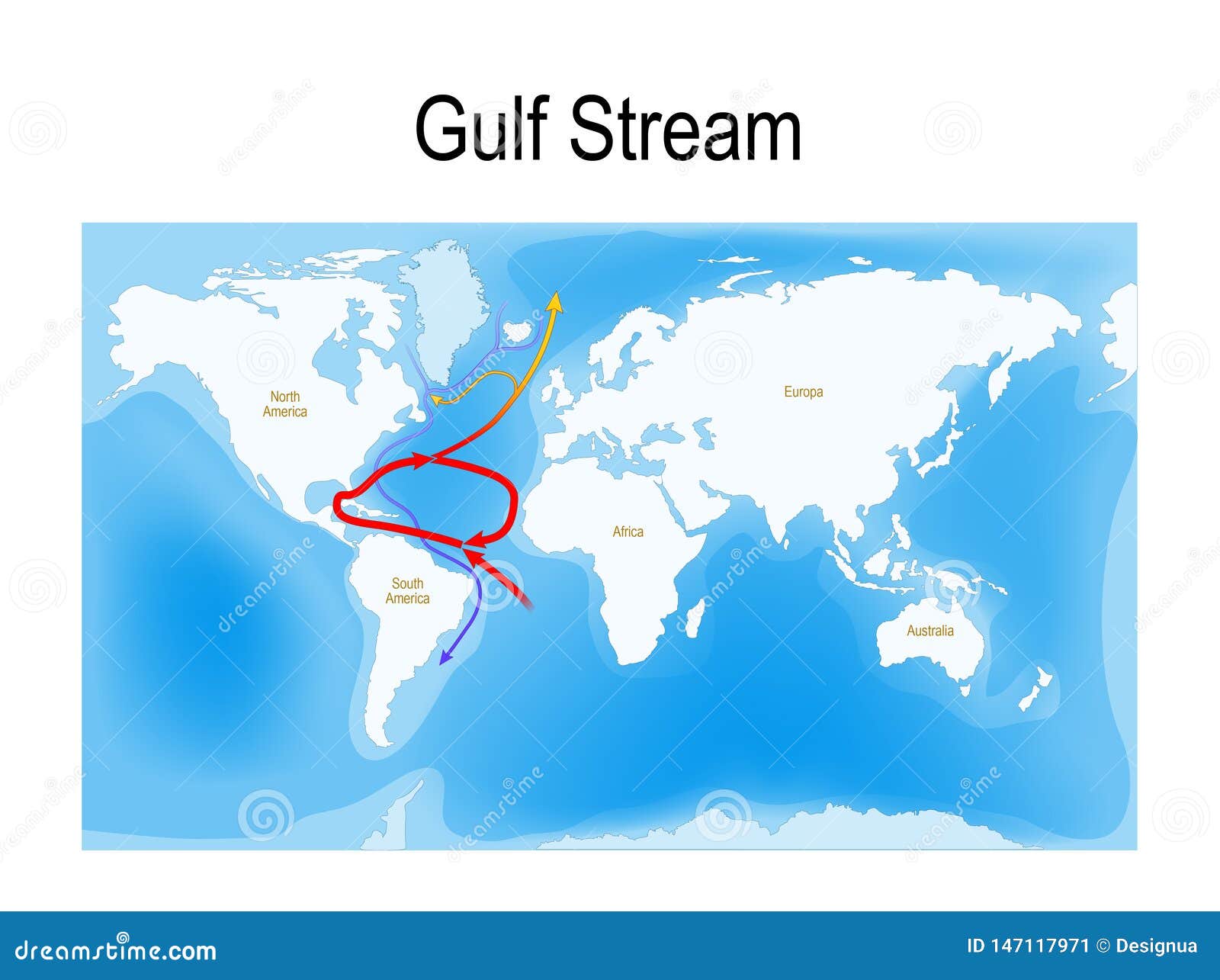

The Gulf is often called the "American Mediterranean," but it’s actually a vital link in the Global Conveyor Belt (the Thermohaline Circulation).

When the Loop Current exits through the Florida Straits, it joins the Antilles Current to become the Florida Current. As it moves up the East Coast of the United States, it becomes the Gulf Stream. This is the same current that carries warm water across the Atlantic to the United Kingdom and Norway. Without the heat provided by the Gulf of Mexico currents, London would have a climate more like Labrador, Canada.

We are currently watching this closely. Some climate models suggest that as polar ice melts and freshens the North Atlantic, the entire "conveyor belt" could slow down. If the exit door (the Florida Strait) gets backed up, it changes the dynamics inside the Gulf. We don't fully know what happens then, but it likely involves higher sea levels for coastal cities like New Orleans and Miami.

Practical Insights for Your Next Trip

If you're heading to the Gulf, understanding these movements isn't just for scientists. It's practical.

- Check the Loop Position: If you’re a deep-sea fisherman, look at satellite altimetry maps (like those from ROFFS or NOAA). You want to find where the warm water meets the cold water. These "fronts" are where the life is.

- Watch the "Red Tide": Karenia brevis is a toxic algae that causes respiratory issues and fish kills. Its movement is entirely dependent on wind-driven surface currents. If there’s a bloom offshore and the wind is blowing "onshore" (toward the beach), stay away.

- Respect the Rip: Look for gaps in the waves or discolored, sandy water moving seaward. That’s a rip current. It’s the most dangerous thing you’ll encounter at the beach—more than sharks or jellyfish.

- Hurricane Season: Between June and November, keep an eye on the Loop Current's northern extent. If a storm is headed your way and the "Heat Content" map shows it crossing the Loop, take the evacuation orders twice as seriously.

The Gulf is a system of loops, rings, and drifts. It’s a complex, beautiful, and sometimes violent machine. Understanding the Gulf of Mexico currents is basically the "owner's manual" for anyone living near or visiting these shores. We're still learning how the deep-sea pulses and the surface winds interact, but one thing is certain: the water is never truly still.

To get the most out of your next coastal visit, check the local "current and tide" charts provided by NOAA. Don't just look at the high tide time—look at the predicted current velocity if you're planning on being in the water. For those interested in the bigger picture, the Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ocean Observing System (GCOOS) provides real-time data from buoys that show exactly what the water is doing at this very second. Use that data. It might just save your fishing trip—or your life.