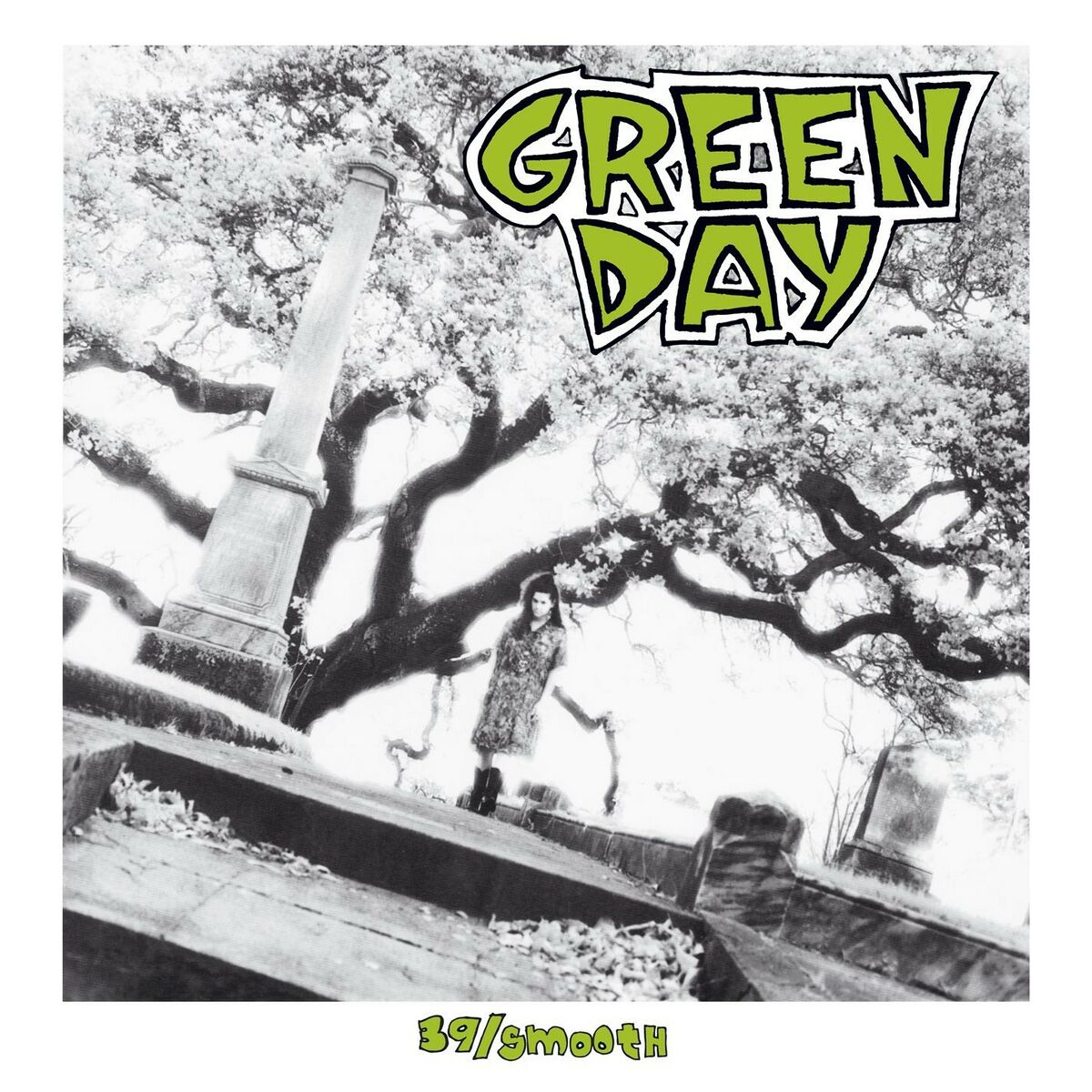

Long before the eyeliner, the concept albums, and the Broadway stage, Green Day was just three kids from the East Bay trying to figure out how to play their instruments without breaking a string. If you’re a fan of Dookie or American Idiot, you might think you know the band’s origins, but honestly, it all truly starts with Green Day 39/Smooth. Released in 1990 on Lookout! Records, this isn't just a debut album; it's a raw, caffeinated snapshot of a subculture that was about to explode.

Most people don't realize that Billie Joe Armstrong and Mike Dirnt were teenagers when they recorded these tracks. You can hear it in the vocals. There’s a certain nasal, earnest quality to the singing that disappeared once they got older and more polished. It's weirdly charming.

The Confusion Around the Name

Let’s clear something up right away because the naming convention of this era is a total mess for new collectors. Green Day 39/Smooth is technically the title of the band's first studio album, but you almost never find it in its original 10-track form anymore.

Back in the day, the band released the 1,000 Hours EP (1989) and the Slappy EP (1990). When it came time to put everything on a CD in 1991, they just mashed them all together and called it 1,039/Smoothed Out Slappy Hours. It's a mouthful. Most fans just refer to the whole era as "39/Smooth," but if you're a vinyl purist, you're looking for the original 10-track pressing on black or green wax.

It was recorded at Art of Ears Studio in San Francisco with producer Andy Ernst. The budget? Probably less than what the band spends on coffee today.

John Kiffmeyer and the Lost Sound

One thing that catches people off guard when listening to Green Day 39/Smooth for the first time is the drumming. It’s not Tré Cool.

📖 Related: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Before Tré joined in late 1990, the man behind the kit was John Kiffmeyer, also known as Al Sobrante. Kiffmeyer’s style was fundamentally different from the heavy-hitting, technical precision Tré eventually brought to the table. Kiffmeyer played with a loose, almost jazzy punk swing.

"Going to Pasalacqua" is the standout here. It’s arguably one of the best songs the band has ever written. Period. The way the bass line carries the melody while the guitar just chugs along—that’s the foundational DNA of every pop-punk band that followed in the late 90s. If you listen closely to the transition between the verses, you can hear the frantic energy of a band that didn't know if they'd ever get to record a second album.

Why the Songwriting Hits Different

Billie Joe Armstrong has always been a hopeless romantic, but on Green Day 39/Smooth, that romanticism is unfiltered. There's no political grandstanding or "Jesus of Suburbia" style rock operas. It’s just songs about girls, boredom, and living in a van.

Take a track like "At the Library." It's a simple story about seeing a girl, wanting to talk to her, and then realizing she’s leaving with someone else. It’s relatable because it’s mundane. This album captures the "East Bay" sound—a specific blend of the melodic sensibilities of The Replacements and the aggressive speed of the Descendents.

- "Don't Leave Me" shows off Mike Dirnt's early prowess. He was already playing lead bass while most punk bassists were just hitting root notes.

- "I Was There" was actually written by Kiffmeyer, giving a rare glimpse into a different lyrical perspective for the band.

- "Road to Acceptance" deals with the universal feeling of not fitting in, a theme they'd milk for the next thirty years.

The production is thin. The guitars sound like they're coming out of a transistor radio sometimes. But that’s the point. It’s "thin" in the way that real, unpolished punk rock should be. It hasn't been compressed to death by a major label.

👉 See also: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

The Lookout! Records Legacy

You can't talk about Green Day 39/Smooth without talking about Larry Livermore and Lookout! Records. At the time, 924 Gilman Street was the epicenter of a DIY revolution. The rules were strict: no major labels, no violence, no jerks.

Green Day were the darlings of that scene until they signed to Reprise for Dookie, at which point they were famously banned from Gilman. It’s a bit of a tragic irony. This album is the purest artifact of that "pure" era.

Interestingly, the rights to this album eventually reverted back to the band after a dispute with the label's later management. It’s now released under their own imprint (via Epitaph or Reprise depending on where you live), but the original Lookout! logo is a badge of honor for anyone lucky enough to own an early pressing.

Misconceptions About the Recording Process

Some people think this album was recorded in a basement on a four-track. It wasn't. While the budget was low, Andy Ernst was a pro. He captured the room. When you listen to the track "The Judge’s Daughter," you can actually hear the physical space they were playing in. The guitar solo in that song is surprisingly technical for a punk kid—Billie Joe was clearly showing off his metal influences (he was a big fan of Randy Rhoads).

Another myth is that the band hated this record once they got famous. Actually, they’ve consistently kept "Going to Pasalacqua" and "Knowledge" (the Operation Ivy cover from the Slappy EP) in their setlists for decades. They know this is where the magic started.

✨ Don't miss: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The Evolution of "Disappearing Boy"

"Disappearing Boy" is a masterpiece of dynamic shifts. It starts with that lonely, echoing guitar riff and builds into a frantic anthem about feeling invisible. It’s the blueprint for the "quiet-loud-quiet" formula that would define 90s alternative rock.

What’s crazy is how much Mike Dirnt contributes here. His backing vocals—those "ooohs" and "aaahs"—add a layer of 60s pop sensibility that set Green Day apart from the more hardcore bands of the time. They weren't afraid to be catchy. In the Gilman scene, being "too poppy" was sometimes seen as a weakness, but Green Day leaned into it.

How to Listen to it Today

If you’re coming from the hits, Green Day 39/Smooth might sound a bit "lo-fi." Don't let that put you off. Turn it up loud.

Don't skip the "paper-thin" tracks. Songs like "16" and "Rest" show a band experimenting with tempo. "Rest" is actually a slow, brooding track that sounds almost nothing like the rest of their catalog. It’s a reminder that even at 17, they were trying to push the boundaries of what a punk song could be.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Listener

To truly appreciate this era of the band, you should go beyond just streaming the album on repeat.

- Seek out the 1,039/Smoothed Out Slappy Hours compilation. This is the definitive way to hear the era, as it includes the two essential EPs that bridge the gap between their earliest garage sounds and the more confident songwriting of the full-length.

- Watch the "Turn It Around: The Story of East Bay Punk" documentary. It provides the necessary context for why this album sounds the way it does. You’ll see the sweaty, cramped clubs where these songs were born.

- Compare the drumming. Listen to "Going to Pasalacqua" and then jump to something from Kerplunk! like "Who Wrote Holden Caulfield?" Notice how Tré Cool’s entry changed the physics of the band. It makes you appreciate Kiffmeyer’s contribution as a unique, separate chapter.

- Analyze the lyrics of "Road to Acceptance." If you're a songwriter, study how Billie Joe uses very simple, concrete imagery to convey abstract feelings of isolation. It’s a masterclass in "less is more."

- Check the liner notes. If you can get your hands on a physical copy, read the thank-you notes. It’s a "who’s who" of the 1990 California punk scene and shows how interconnected these bands were.

Green Day 39/Smooth isn't just a historical curiosity. It’s a vibrant, living record that still carries the smell of cheap beer and van exhaust. It’s the sound of a band that had no idea they were about to change the world, and that’s exactly why it’s so good.