You’ve probably heard the warnings. People tell you not to watch Grave of the Fireflies unless you’re prepared to be emotionally destroyed for a week. It’s got this massive reputation as the "saddest movie ever made," which is honestly a bit of a disservice. It’s not just a tear-jerker. It’s a brutal, uncompromising look at pride and the cost of isolation during the firebombing of Kobe in 1945. Most people go into it expecting a simple anti-war message, but the reality is way more complicated than that.

Isao Takahata, the director and co-founder of Studio Ghibli, actually spent years trying to push back against the "anti-war" label. That sounds weird, right? But he was very specific about his intent. He didn't want people to just feel bad for the kids; he wanted to show what happens when a young boy tries to live a life of total self-reliance while the world around him is literally burning.

The True Story Behind the Screenplay

The movie is based on a 1967 semi-autobiographical short story by Akiyuki Nosaka. He lived through the firebombing of Kobe. He watched his sisters die. He lived with a guilt so heavy that the book was basically a public apology to his younger sister, Keiko. In real life, Nosaka admitted he wasn't as kind to his sister as Seita is to Setsuko in the film. He once hit her to get her to stop crying. He ate food that he probably should have shared.

When you watch Grave of the Fireflies, you’re seeing a sanitized, or maybe "idealized" version of Nosaka’s trauma. Seita is a tragic hero in the movie, but even then, Takahata leaves breadcrumbs showing that Seita’s own pride killed them both.

The Problem with Seita’s Pride

A lot of viewers hate the aunt. You know the one—the relative they stay with who complains about them not working. We’re conditioned to see her as the villain because she’s mean to these poor orphans. But if you look at it through the lens of 1945 Japan, she’s just trying to keep her own family alive. Seita has money. He has a bank account with 7,000 yen (a fortune back then). He refuses to work. He refuses to help the war effort.

🔗 Read more: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Takahata wasn't trying to make Seita a perfect martyr. He was criticizing the "me-first" attitude that he saw creeping into Japanese youth culture in the 1980s. He felt that if a modern kid was put in that situation, they’d act just like Seita—isolating themselves from society because they didn't want to deal with the rules. That isolation is what leads to the tin of fruit drops being filled with marbles. It’s what leads to the malnutrition.

Why the Animation Matters More Than You Think

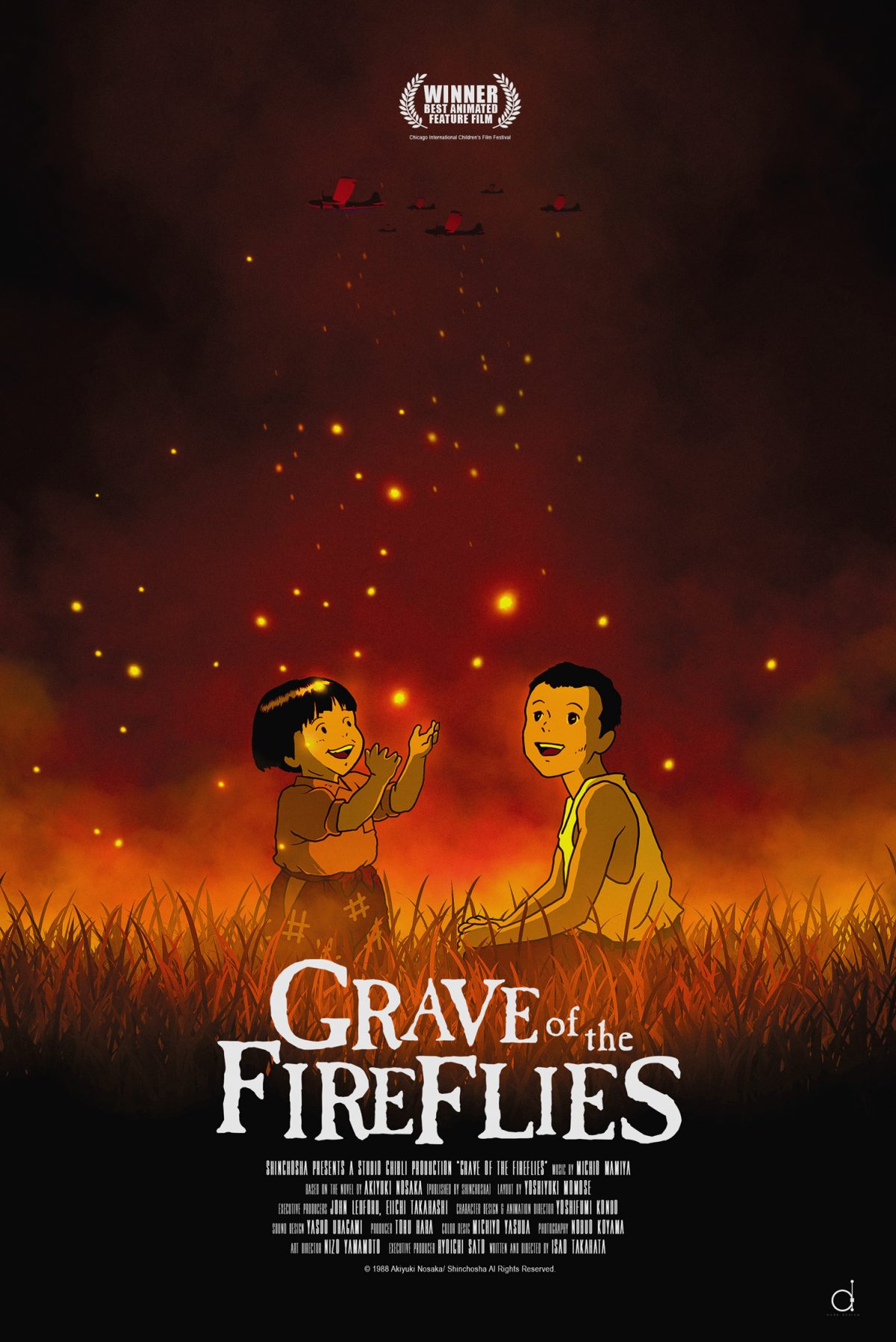

Ghibli is famous for "the Ghibli look"—lush greens, beautiful food, and flowing water. In this film, they used a different technique. They used brown linework instead of the traditional black. It gives the whole movie a dusty, filtered, "memory-like" feel. It makes the fire feel hotter and the shadows deeper.

There’s this one scene where Seita watches the fireflies. It’s beautiful. Then Setsuko dies. The metaphor isn't subtle, but it's effective. Fireflies live for a day. The B-29 bombers dropping incendiary gel look like fireflies from a distance. The kids are fireflies. Everything beautiful in this movie is dying.

The Crayon-Box Color Palette of Tragedy

The contrast between the "spirit" world—where we see Seita and Setsuko in a red-tinted limbo—and the "real" world is jarring. The red tint signifies that they are stuck. They are ghosts of a failed society. It’s worth noting that the film was originally released as a double feature with My Neighbor Totoro. Imagine that for a second. You watch a giant forest cat fly around on a bus, and then you watch two children starve to death in a bomb shelter. It was a box office disaster initially because, obviously, parents didn't know how to handle that tonal whiplash.

💡 You might also like: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

Fact-Checking the History

The firebombing of Kobe wasn't a minor event. On March 16–17, 1945, over 300 B-29s dropped 2,300 tons of incendiaries. It destroyed nearly half the city. This isn't just "background" for the movie; it's the antagonist.

- The Fruit Drops: Sakuma Drops are a real brand. The company actually went out of business recently (in 2023), which felt like the end of an era for fans of the movie.

- The Father: Seita’s father is in the Imperial Japanese Navy. Seita’s obsession with his father’s "invincible" fleet is his undoing. He can't accept that the Navy is gone because it would mean his entire worldview—and his safety net—is gone.

- The Shelter: People really did live in those hillside bunkers. They were damp, mosquito-ridden, and completely unsuitable for children.

Honestly, the most heartbreaking thing about Grave of the Fireflies is that it’s not a story about how war is bad for soldiers. It’s about how war turns civilians into people they don't recognize. The aunt isn't evil; she's hungry. The farmer who beats Seita for stealing isn't a monster; he's trying to protect his crop so his own kids don't starve.

Misconceptions About the Ending

People think the ending is about Seita and Setsuko finding peace. It’s not. If you watch the very first scene, you see Seita’s spirit in the train station. He’s surrounded by modern Japanese commuters who are ignoring him. This was Takahata’s biggest "hidden" message. He was saying that modern society has forgotten the sacrifices and the suffering of that generation. We walk right past the "ghosts" of our history every day without looking up from our phones (or 1980s equivalent).

The movie starts with the line: "September 21, 1945... that was the night I died."

📖 Related: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

It tells you the ending in the first ten seconds. The rest of the film is just a post-mortem. It removes the "hope" factor so you can focus on the "why."

How to Watch It Without Losing Your Mind

If you’re planning on watching it for the first time, or re-watching it to see these nuances, keep a few things in mind:

- Watch the background characters. Don't just focus on the kids. Look at the faces of the people in the streets. They are hollowed out.

- Listen to the sound design. The silence in this movie is heavy.

- Think about the "Tinned Food" metaphor. In post-war Japan, canned goods were symbols of the West and of survival. The empty tin becomes a coffin.

Grave of the Fireflies is a masterpiece of empathy, but it’s also a warning about what happens when we let pride cut us off from our community. It’s a hard watch, but it’s a necessary one. It reminds us that "never again" isn't just a political slogan—it's a plea for the children who are always the first to pay the price for the mistakes of adults.

Actionable Insights for the Viewer:

- Research the Kobe Firebombing: To truly understand the stakes, look up the March 1945 raids. The scale of destruction explains the "every man for himself" mentality of the supporting characters.

- Analyze the "Ghost" Scenes: Re-watch the opening and closing scenes. Notice the red tint. These are the only times the characters are "safe," but they are also trapped in a loop of their own tragedy.

- Compare to "In This Corner of the World": If you want a different perspective on the same era, watch this 2016 film. It offers a more communal, less "isolated" look at civilian life during the war, providing a perfect counterpoint to Seita’s journey.

- Check the Source Material: Read Akiyuki Nosaka’s original short story. It’s even darker and provides a raw, unfiltered look at the survivor's guilt that fueled the creation of this film.