Black and white wasn't just a stylistic choice for George Clooney. It was a necessity. When you’re making a film about the gray areas of American morality, sometimes you need the stark contrast of monochrome to see the truth. Good Night, and Good Luck isn't just a period piece; it’s a warning shot that feels louder today than it did in 2005. Honestly, watching it now, you’ve got to wonder if Edward R. Murrow would even recognize the media landscape we’re currently navigating.

The movie centers on the 1954 conflict between veteran radio and television journalist Edward R. Murrow and U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy. It was a high-stakes poker game played in the CBS studios. McCarthy was hunting communists; Murrow was hunting for the soul of American democracy. Most people think of this as a simple "hero vs. villain" story, but it's way more complicated than that. It’s about the terrifying cost of speaking up when everyone else is whispering.

The Murrow-McCarthy Feud: What Most People Get Wrong

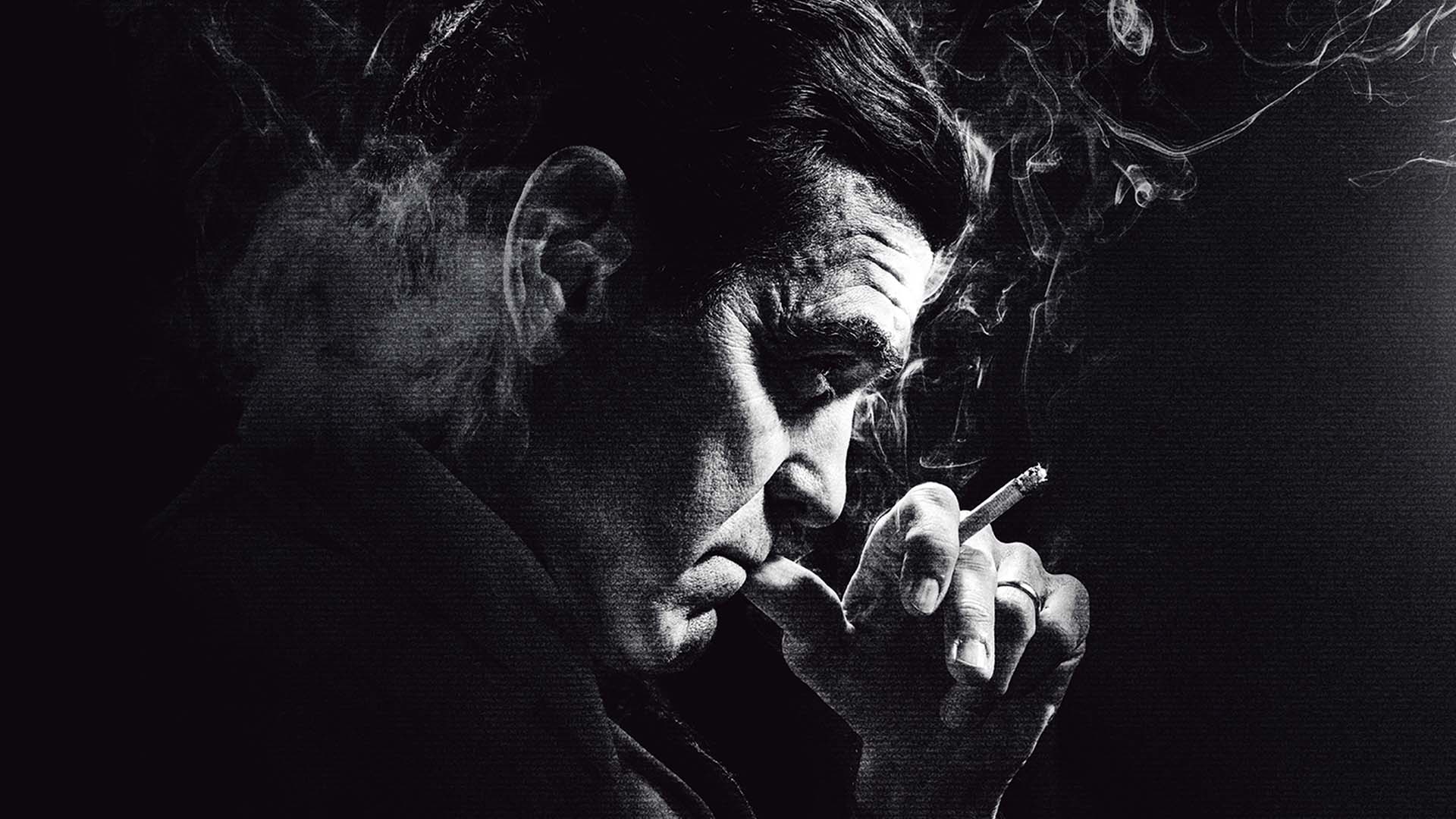

We like to remember Murrow as this untouchable titan of integrity. David Strathairn plays him with this incredible, simmering stillness—constantly engulfed in a cloud of cigarette smoke. But the reality of the Good Night, and Good Luck movie is that it shows Murrow was scared. He wasn't some fearless crusader who knew he would win. He was a guy who knew he might lose his job, his reputation, and his network.

McCarthy wasn't just some fringe politician either. He had real power. He used the "Red Scare" to ruin lives, and for a long time, the press just let him do it. They were afraid of being labeled "un-American." Sound familiar? The film captures that specific brand of institutional dread. It’s the feeling of being in a room where everyone knows something is wrong, but nobody wants to be the first person to say it out loud.

One of the most genius moves Clooney made was using actual archival footage of Joseph McCarthy. He didn't hire an actor to play the Senator. He just used the real guy. Critics at the time actually complained that the "actor" playing McCarthy was too over-the-top. That’s the irony. The real-life McCarthy was so theatrical and aggressive that modern audiences thought it was bad acting. It just goes to show that reality is often stranger than fiction.

Behind the Scenes at CBS: The Cost of Truth

The film spends a lot of time in the cramped, smoky offices of CBS News. It’s claustrophobic. You feel the weight of the ceiling pressing down on the characters. This wasn't a big-budget epic; it was a character study. Clooney shot the whole thing in about five weeks.

There’s a subplot involving Joe and Shirley Wershba, played by Robert Downey Jr. and Patricia Clarkson. They’re a married couple working at the network who have to keep their marriage a secret because of company policy. It’s a subtle touch. It reminds us that while Murrow was fighting for the First Amendment, the "little people" at the network were fighting just to keep their livelihoods.

🔗 Read more: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

Why the Cinematography Changes Everything

Robert Elswit, the cinematographer, deserves a lot of credit here. He used high-contrast lighting to make the newsroom look like a battlefield. The light reflects off the chrome of the microphones and the glasses of the producers. It’s sharp. It’s cold.

- The Smoke: Cigarettes are practically a character in this movie. They represent the anxiety of the era.

- The Close-ups: Clooney stays tight on faces. You see every beads of sweat, every twitch of the lip.

- The Sound: It’s not a loud movie. It’s a movie of whispers, typewriter clicks, and the low hum of studio lights.

The "Wires and Lights in a Box" Speech

The emotional climax of the Good Night, and Good Luck movie isn't a physical fight. It’s a speech. Murrow’s address to the Radio-Television News Directors Association in 1958 serves as the film's bookends. He warned that television was being used to distract and delude the public. He said that if it didn't teach or illuminate, it was "merely wires and lights in a box."

Think about that for a second. In 1958, he was worried about the "decadence, escapism, and insulation" of the media. If he could see the algorithmic feeds of 2026, he’d probably lose his mind. Murrow’s point was that the medium itself is neutral; it’s the people who run it who determine its value.

The movie basically argues that the news isn't supposed to make you feel good. It’s supposed to make you think. Fred Friendly, played by George Clooney himself, is the producer who has to balance the books. He’s the one who has to tell Murrow that their sponsors are dropping out. Alcoa, the big aluminum company, didn't want to be associated with a controversial program. It’s a reminder that journalism has always been at the mercy of the people who pay the bills.

The Tragic Figure of William Paley

Frank Langella gives a haunting performance as William Paley, the head of CBS. He’s not a villain, but he’s not exactly a hero either. He’s a businessman. He liked Murrow, but he liked his network more. There’s a heartbreaking scene where Paley tells Murrow he’s moving the show to a "graveyard" Sunday afternoon slot.

Paley's argument was simple: "I don't want a stomach ache every time you take a stand."

💡 You might also like: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

It’s the ultimate corporate sentiment. It shows the friction between the need for profit and the duty to inform. The film doesn't give us a happy ending where everything is fixed. McCarthy was eventually censured, sure, but Murrow’s style of hard-hitting journalism was already being pushed to the margins. The era of "infotainment" was beginning.

Historical Accuracy vs. Narrative Flair

While Clooney was obsessive about the details, some historians point out that the film simplifies the timeline. The fight against McCarthy was a long, slow burn, not a single knockout blow. Others argue that the film ignores the fact that Murrow himself was sometimes cautious. He wasn't always the first to jump into the fray.

But honestly? That makes the story better. It shows that courage isn't the absence of fear or hesitation. It’s doing the right thing even after you’ve spent a long time being quiet. The movie captures the essence of the 1950s—the paranoia, the stifling conformity, and the rare moments of brilliance that broke through the fog.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Viewer

If you’re watching the Good Night, and Good Luck movie today, don't just treat it as a history lesson. Use it as a lens to view your own media consumption. Here’s how you can apply Murrow’s philosophy to the modern world:

1. Vet Your Sources Like a Producer

Murrow and Friendly spent weeks verifying their facts before going on air. They knew that one mistake would give McCarthy the leverage to destroy them. In an age of instant gratification, we often share things before we even read them. Take thirty seconds to check a source. Is it a reputable news organization or a random blog with an agenda?

2. Recognize the "Echo Chamber" Effect

McCarthy thrived because he created an atmosphere of fear where people were afraid to disagree. Modern algorithms do something similar by only showing us what we already believe. Seek out dissenting opinions. Not the crazy stuff, but the well-reasoned arguments from the other side.

📖 Related: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

3. Understand the Difference Between News and Opinion

Murrow was an opinionated journalist, but he grounded his opinions in objective facts. He showed the footage of McCarthy's own words and let the audience decide. Today, the line between "news" and "commentary" is invisible. When you’re watching a clip, ask yourself: "Is this person telling me what happened, or telling me how to feel about what happened?"

4. Support Independent Journalism

The biggest threat to Murrow wasn't McCarthy; it was the loss of sponsorship. If you value deep-dive reporting, you have to pay for it. Whether it’s a subscription to a local paper or a donation to a non-profit newsroom, quality journalism requires resources.

Ultimately, the Good Night, and Good Luck movie isn't about the past. It's about right now. It's about the responsibility we have to be informed citizens. As Murrow famously said, "We are not descended from fearful men." The movie challenges us to live up to that.

The film ends not with a celebration, but with a quiet realization. Murrow and Friendly have won a battle, but the war for the integrity of the airwaves is just beginning. They sit in the studio, the red "On Air" light fades, and the world moves on. But the questions they raised are still hanging in the air, waiting for us to answer them.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

- Watch the actual "See It Now" episodes: Many of the real Murrow broadcasts featured in the film are available in public archives or on video platforms. Seeing the real Murrow's delivery provides a fascinating comparison to Strathairn's performance.

- Research the Army-McCarthy Hearings: To see how the Senate finally turned against McCarthy, look into the 1954 hearings where Joseph Welch famously asked, "Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last?"

- Read "The Murrow Boys": For a deeper look at the team of journalists Murrow assembled during WWII and the early days of TV, this book by Stanley Cloud and Lynne Olson is the gold standard.