Listen to those first few notes of the flute. You know the ones. It’s a fluttering, bird-like chirp that immediately makes you want to quit your job, pack a van, and drive until the pavement turns into dirt. That is the magic of Going Up the Country by Canned Heat. It isn't just a song; it's a literal siren song for anyone who has ever felt suffocated by the city.

Most people recognize it as the "unofficial anthem" of Woodstock. When the 1970 documentary hit theaters, this track played over the opening montage of hippies rolling into Max Yasgur’s farm, forever cementing it as the sound of the counterculture. But there is a lot more to the story than just tie-dye and mud.

Honestly, the song’s origins go back way further than 1968.

The 1920s Blues Secret Behind the Hit

A lot of folks assume Alan "Blind Owl" Wilson wrote the whole thing from scratch. He didn't. Wilson was a massive record collector and a total scholar of early Delta blues. He basically "borrowed" the melody and the structure from a 1928 track called "Bull Doze Blues" by Henry Thomas.

Thomas was a songster from Texas who played a set of reed pipes (quills) while strumming a guitar. If you listen to the original 78rpm record, it’s uncanny. Wilson didn't just cover it; he transformed it. He kept that distinct, jaunty flute-like hook—originally played on the quills by Thomas—and updated the lyrics to reflect the 1960s "back to the land" movement.

It’s a perfect example of how the blues evolved.

Canned Heat wasn't just some pop-rock group trying to cash in on a trend. They were purists. They actually helped rediscover old blues legends like Son House. When Wilson sat down to arrange Going Up the Country by Canned Heat, he was paying homage to the roots while creating something that sounded entirely fresh for the psychedelic era.

👉 See also: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

That Voice: Why Alan Wilson Sounded Like That

Let’s talk about the vocals. It’s high. It’s thin. It’s almost ghost-like.

Wilson had this incredible falsetto that defied the "tough guy" blues singer trope of the time. While most white blues-rockers were trying to growl like Muddy Waters, Wilson sounded like a fragile kid from Massachusetts. It worked. His voice gave the song a sense of innocence. When he sings about going to a place "where the water tastes like wine," you actually believe him. You don't think he's going there to party; you think he's going there because he can't survive anywhere else.

Wilson was a complex guy. He was a brilliant musician but a total misfit. He was a dedicated environmentalist long before it was "cool" or mainstream. He’d sleep outdoors just to be closer to nature. Sadly, he died at the age of 27 in 1970, just a few weeks before Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. Because he wasn't a flashy frontman like Morrison or Jagger, his contribution to music history often gets sidelined.

But Going Up the Country by Canned Heat remains his masterpiece.

Woodstock and the Birth of a Legend

The performance at Woodstock in 1969 changed everything. Canned Heat played on Saturday night, right when the festival was reaching its peak of chaotic energy.

Interestingly, the band almost didn't make it. There was massive internal drama. Henry Vestine, the lead guitarist, had quit the band just days before the festival after an onstage fight with bassist Larry Taylor. They had to scramble to find a replacement, eventually bringing in Harvey Mandel. Despite the tension, they delivered a set that defined a generation.

✨ Don't miss: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

The lyrics hit the 500,000 people in that crowd right in the chest:

"I'm goin' where the water tastes like wine / We can jump in the water, stay drunk all the time."

In the context of the Vietnam War and the civil unrest of the late 60s, "the country" wasn't just a geographical location. It was a state of mind. It was a refusal to participate in a system that felt broken.

Why the Song Never Ages

You’ve probably heard this track in a dozen commercials. Geico used it. Miller Lite used it. It’s been in movies like Forrest Gump and Into the Wild.

Why does it keep coming back?

It’s the tempo. The song moves at a perfect 12-bar blues shuffle that feels like a heartbeat. It’s optimistic. Most blues songs are about loss, heartbreak, or being broke. This one is about hope. It’s about the "big escape."

🔗 Read more: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

Even if you’re stuck in a cubicle in 2026, the moment Jim Horn’s flute intro kicks in, you feel a sense of relief. It’s a mental vacation.

Common Misconceptions About the Song

- It’s about drugs: While "stay drunk all the time" is a literal lyric, the song is more about freedom from societal pressure than literal intoxication.

- The flute is a synthesizer: Nope. That’s a real flute played by Jim Horn, a legendary session musician who also worked with the Beach Boys and George Harrison.

- Canned Heat was a "one-hit wonder": Not even close. They had "On the Road Again" and "Let’s Work Together," both of which were massive. They were one of the most respected blues-rock bands on the planet.

The Technical Brilliance of the Composition

Technically, the song is incredibly tight. Larry Taylor’s bass line is a masterclass in the "boogie" style. It doesn't overplay. It just provides this rolling foundation that allows the flute and Wilson’s vocals to float on top.

If you're a musician, try playing along to it. You’ll realize the timing is deceptively tricky. It’s got a swing that most modern rock drummers struggle to replicate. Fito de la Parra, the band's drummer, kept it simple but incredibly steady. It’s that "chug-a-chug" rhythm that makes it so infectious.

How to Experience the Song Today

To really appreciate Going Up the Country by Canned Heat, you have to look past the "classic rock radio" sheen.

- Listen to the Mono Mix: If you can find the original mono single version, do it. It has a punch and a clarity that the muddy stereo remasters often lose.

- Watch the Woodstock Footage: Don't just listen. See the band on stage. Look at Alan Wilson’s face. He looks completely locked in, almost in a trance.

- Check out Henry Thomas: Go back to the source. Listen to "Bull Doze Blues." It will give you a profound respect for how Wilson reimagined the past to create the future.

Canned Heat proved that you could be a "blues revivalist" without being a museum piece. They took 1920s Texas folk-blues and turned it into the definitive anthem for the greatest outdoor party in human history.

That’s a legacy that isn't going anywhere.

Actionable Insights for Music Lovers

If you want to dig deeper into this era of music or the "boogie" sound, here is how to spend your next afternoon:

- Explore the "Canned Heat Cookbook": This is a great compilation album that gives you the best of their early years. It’s the best entry point for the band.

- Study the 1920s Songsters: Beyond Henry Thomas, look up artists like Charley Patton or Mississippi John Hurt. You’ll hear where the DNA of 60s rock actually came from.

- Support the "Blind Owl" Legacy: Alan Wilson was a pioneer in environmentalism. Look into the Music Cares foundations or environmental groups that focus on the California Redwoods—a cause Wilson was incredibly passionate about before his passing.

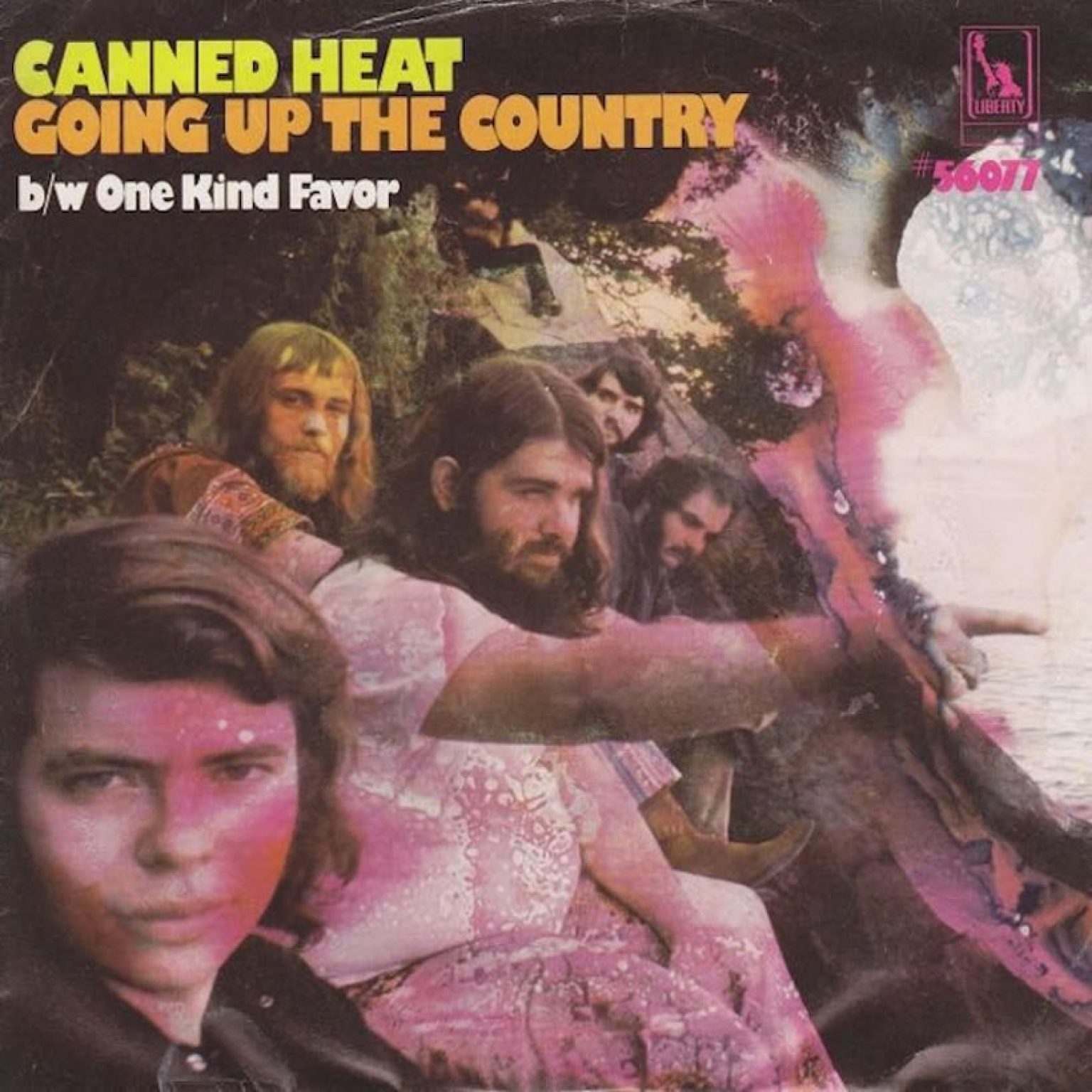

- Check Your Vinyl Pressings: If you’re a collector, look for the Liberty Records blue label pressings of Living the Blues. That’s the double album where "Going Up the Country" first appeared. The sound quality on those original pressings is vastly superior to the 1980s reissues.