Money is a funny thing, isn't it? Not "ha-ha" funny, but the kind of funny that makes you want to stare into a solar eclipse until your retinas sizzle. Kurt Vonnegut knew this better than anyone. In 1965, he dropped God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, a novel that basically functions as a giant middle finger to the idea that being rich makes you better than anyone else. Honestly, if you’ve ever looked at a billionaire’s Twitter feed and felt a mild sense of nausea, this book is for you.

It's about Eliot Rosewater. He’s the heir to a massive fortune, a man who survived the horrors of World War II only to realize that the "American Dream" is mostly just a giant shell game. Eliot decides to leave his fancy life in New York and move to a decaying, pathetic town in Indiana called Rosewater. Why? To love people who are essentially "useless" in the eyes of capitalism. He spends his days drinking bottom-shelf gin, answering a telephone, and telling poor people he loves them.

People think he's crazy. Of course they do. In a world where your value is tied to your bank account, loving the "unlovable" is a radical act of insanity.

The Problem with the Rosewater Fortune

Let’s talk about the money. The Rosewater Foundation is a legal loophole designed to keep a massive pile of cash out of the hands of the government. It's a "perpetual motion machine" of wealth. Vonnegut describes the history of this money with a cynical precision that feels uncomfortably relevant in 2026. He traces it back to Noah Ames Rosewater and Parsons Rosewater, two brothers who profited off the Civil War. One fought; the other stayed home and made a killing.

That’s the DNA of the fortune. It’s built on opportunism and greed.

Eliot, however, is haunted by a "click" in his brain. While serving as an infantry captain, he accidentally killed three German firemen, thinking they were soldiers. This trauma—combined with the sheer absurdity of his inherited wealth—breaks him. Or maybe it fixes him. It depends on who you ask in the book. His father, Senator Liston Rosewater, represents the old guard. He’s obsessed with "merit" and thinks his son is a disgrace.

Then you have Norman Mushari. He’s the antagonist, a predatory lawyer who wants to prove Eliot is insane so he can divert the Rosewater fortune to a distant, "sane" relative. Mushari is the personification of every corporate lawyer who ever looked for a loophole to screw someone over. He’s small, he’s conniving, and he thinks Eliot’s kindness is the ultimate proof of a broken mind.

Why This Book Hits Different After Slaughterhouse-Five

Most people find their way to Vonnegut through Slaughterhouse-Five. That’s the big one. The "So it goes" one. But God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater is actually where Kilgore Trout makes his first appearance. If you aren't a Vonnegut nerd, Trout is the recurring character who writes terrible sci-fi novels with brilliant ideas.

🔗 Read more: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

In this book, Trout is Eliot’s idol.

Trout’s stories provide the philosophical backbone for Eliot’s breakdown. There’s one specific story Trout tells about a funeral for a great scientist where the mourners are all robots. It’s bleak. It’s weird. It’s classic Vonnegut. But it highlights the core question of the novel: What are people for? When machines take all the jobs and the frontier is closed, what do we do with the "discarded" humans? Eliot’s answer is simple: "God damn it, you’ve got to be kind."

The "Baptism" Scene and the Firefighters

Eliot has a weird obsession with volunteer firefighters. He sees them as the only people in America who are purely, selflessly good. They don't get paid to save lives; they just do it because it needs doing.

One of the most famous quotes in literature comes from this book, during a scene where Eliot "baptizes" two twin babies. He tells them:

"Hello, babies. Welcome to Earth. It’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It’s round and wet and crowded. At the outside, babies, you’ve got about a hundred years here. There’s only one rule that I know of, babies—'God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.'"

It’s not poetic in the traditional sense. It’s blunt. It’s sort of sweaty and desperate. But it’s the most honest advice anyone has ever given a newborn.

The Legal Battle for Sanity

The second half of the book turns into a bit of a legal thriller, albeit a very strange one. Norman Mushari is digging up dirt. He’s looking at Eliot’s drinking, his weird letters, and his refusal to live like a millionaire.

💡 You might also like: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

The climax happens in a bus station.

Eliot has a full-blown mental collapse—or a breakthrough. He sees the city of Indianapolis being consumed by a "fire storm." It’s a vision of the end of the world, or maybe just the end of his world. He winds up in a mental institution, and the fate of the Rosewater fortune hangs in the balance.

How does he win? It’s brilliant.

To prove he’s "sane" and to stop the fortune from being stolen by the distant cousins, Eliot simply acknowledges all the illegitimate children in the county—who people claimed were his because he was so nice to their mothers—as his legal heirs. He uses the very laws designed to protect wealth to redistribute it. He turns the "perpetual motion machine" against itself.

It’s a masterstroke of satirical writing. He doesn't win by being a saint; he wins by being a better lawyer than the lawyers.

Common Misconceptions About the Book

A lot of people think this is just a "socialist" book. That’s a bit of a lazy take. Honestly, Vonnegut is more interested in the soul than the economy. He’s asking what happens to the human spirit when it’s told it has no value.

- Misconception 1: Eliot is a hero. He isn't, really. He’s a mess. He’s a functional alcoholic who neglects his wife, Sylvia, until she has a nervous breakdown of her own. Vonnegut isn't saying Eliot is perfect; he's saying even a broken person can choose kindness.

- Misconception 2: The book is dated. The references to 1960s Indiana might feel old, but the talk about "automated" poverty and the "savage" nature of American greed? That’s more relevant now than it was then.

- Misconception 3: It's a comedy. Well, it's a Vonnegut comedy. Which means you'll laugh, and then you'll want to stare into the middle distance for twenty minutes thinking about your own mortality.

The Legacy of Rosewater in Modern Culture

You can see the fingerprints of God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater all over modern media. Shows like The Good Place or even the cynicism of Succession owe a debt to Eliot Rosewater’s struggle.

📖 Related: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

The idea of the "Useless Class" is a term that modern historians like Yuval Noah Harari use today. Vonnegut was writing about it sixty years ago. He saw a world where humans were being replaced by "cleverness" and "efficiency," and he hated it. He wanted a world where people were valued just because they were breathing.

If you're looking to actually get something out of this book besides a headache from the gin references, look at how you treat people who can do absolutely nothing for you. That’s the Rosewater Test. It’s easy to be nice to your boss. It’s hard to be nice to the guy screaming at a mailbox.

How to Actually Apply the "Rosewater" Philosophy Today

You don't have to give away a billion dollars to live like Eliot. Mostly because you probably don't have a billion dollars. But the core of the book is about resisting the urge to categorize people by their "utility."

- De-link worth from work. Next time you meet someone, try not to ask "What do you do?" for at least ten minutes. Talk about anything else. Their favorite bird. The last thing they ate that made them happy. Anything.

- Support the "Unproductive." In a world obsessed with side hustles and "grindset" culture, doing something purely for the joy of it—or helping someone who can't "scale" your investment—is a form of rebellion.

- Read the rest of the "Rosewater" trilogy. While not an official trilogy, Vonnegut fans usually group this with Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions. Reading them in order gives you a terrifyingly clear picture of how Vonnegut saw the American psyche disintegrating.

- Volunteer for the sake of it. Like the firefighters Eliot loved, find a way to contribute to your community that doesn't involve a tax write-off or a LinkedIn post.

The ending of the book isn't a happy one in the traditional sense. Eliot is still in a sanitarium. The world is still greedy. But for a brief moment, he broke the machine. He proved that even in a world governed by cold, hard cash, a person can choose to be a "drunk, eccentric, kind-hearted" human being instead.

And really, what more can we ask for?

If you're going to read it, grab the Dell paperback version if you can find it. There's something about the smell of those old 1970s copies that makes the satire bite just a little bit harder. Plus, the cover art back then was way weirder.

Stop worrying about being useful. Just try being kind. It’s a lot harder, but the "click" in your brain might finally stop bothering you.

Next Steps for the Vonnegut Enthusiast:

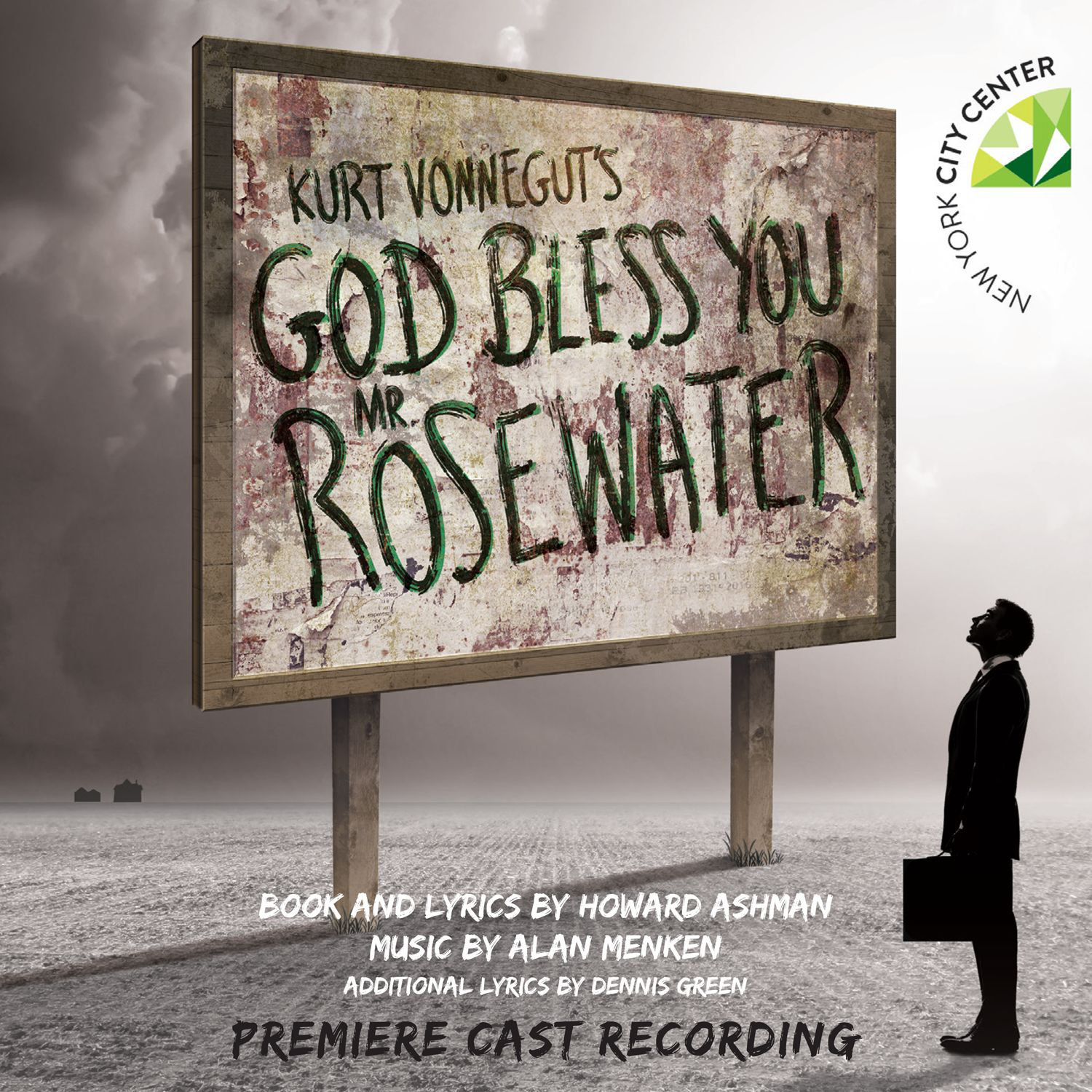

To truly grasp the scope of the Rosewater influence, your next move should be tracking down a copy of the 1982 musical adaptation. Yes, there is a musical. It was written by Howard Ashman and Alan Menken—the same duo behind The Little Shop of Horrors and The Little Mermaid. It’s a bizarre, beautiful piece of theater that captures the "kindness vs. capitalism" struggle through song. Watching or listening to it after reading the novel provides a fascinating look at how Eliot's radical empathy translates to the stage. It’s a deep dive that most casual readers miss, but it's essential for understanding the cultural footprint of the Rosewater legacy.