Politics in the late 1800s was a blood sport. Forget polite discourse or nuanced white papers. If you wanted to take down a senator or a corporate titan in 1875, you didn't write a scathing op-ed that only the elite could read. You drew him as a bloated vulture picking at the bones of the taxpayer. Gilded Age political cartoons weren't just "art." They were tactical weapons. They were the TikToks of their day—vicious, instantly recognizable, and capable of ending a career before the ink even dried.

Honestly, we tend to think of history as this dry, dusty thing. But the era of Mark Twain and John D. Rockefeller was loud. It was messy. Immigrants were flooding into New York, the wealth gap was widening into a canyon, and corruption was basically the national pastime. In this chaos, the cartoonists became the unofficial Fourth Estate. They took complex financial scandals like the Crédit Mobilier and boiled them down into a single, devastating image that a person who didn't even speak English could understand at a glance.

The Man Who Invented the Modern Takedown

Thomas Nast is the name you've probably heard if you've ever glanced at a history textbook. He’s the guy who gave us the Republican elephant and the Democratic donkey. He basically created the modern American version of Santa Claus, too. But his real legacy? He absolutely dismantled William "Boss" Tweed and the Tammany Hall machine.

Tweed once famously said, "I don't care a straw for your newspaper articles, my constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them damned pictures!" That's the whole Gilded Age political cartoons phenomenon in a nutshell. Tweed was the head of a massive political machine that stole somewhere between $30 million and $200 million from New York City. Nast didn't just report on it. He drew Tweed as a bag of money. He drew him as a giant thumb crushing the city.

The impact was visceral. When Tweed eventually fled the country to escape prosecution, he was recognized in Spain. How? Not because of a grainy photograph or a physical description in a ledger. A Spanish official recognized him from a Nast cartoon. Imagine a meme being so effective it acts as a global "Wanted" poster before the internet even existed. That is the level of power we’re talking about here.

👉 See also: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

The Evolution of the Visual Language

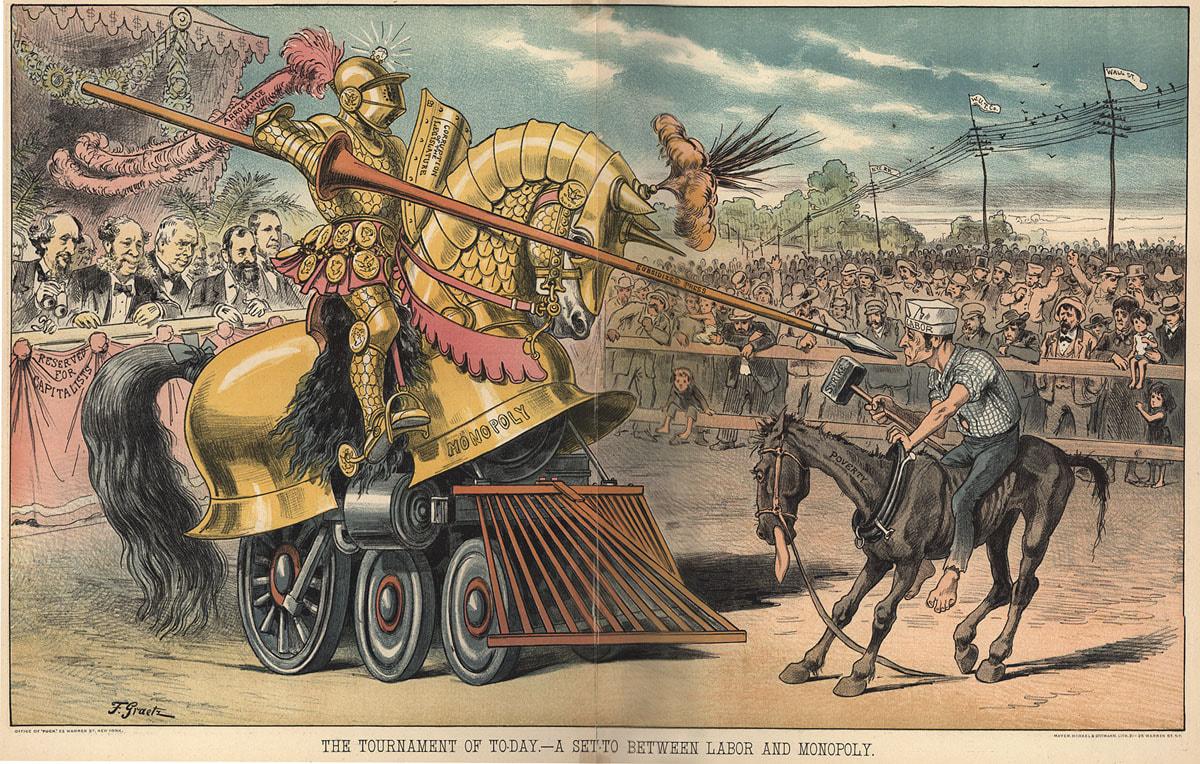

It wasn't just Nast, though. You had magazines like Puck and Judge that turned satire into a massive business. Joseph Keppler, who founded Puck, brought a more "European" style to the table. While Nast used harsh, jagged woodcut-style lines that felt like a punch to the gut, Keppler used lithography. It was colorful. It was lush. It looked like something you'd want to hang on your wall, until you realized the "beautiful" image was actually a scathing critique of monopolists.

Take Keppler's famous 1889 cartoon, "The Bosses of the Senate." You've likely seen it in a classroom. It depicts the U.S. Senate floor, but the senators are tiny, insignificant figures compared to the massive, bloated "Money Bags" looming over them. Each bag represents a different trust: Steel, Copper, Standard Oil. The door for the people is locked. The door for the monopolists is wide open. It’s not subtle. It’s a sledgehammer.

Why These Drawings Actually Worked

It’s easy to dismiss these as just funny drawings, but they functioned as a crucial bridge in a bifurcated society. In the 1880s, the literacy rate was rising, but it wasn't universal. Furthermore, for the millions of new immigrants landing at Ellis Island, the dense political jargon of the New York Times was a brick wall. But a cartoon? You don't need a PhD to understand a drawing of a giant snake labeled "Monopoly" swallowing a farmer.

- Symbols became shorthand. Once the public learned that a certain hat meant "The Trusts" or a certain chin meant "Tammany Hall," the cartoonist didn't have to explain anything anymore.

- They bypassed the brain and hit the gut. Text makes you think; images make you feel. Seeing the "Standard Oil Octopus" wrapping its tentacles around the Capitol building triggers a fear response that a 5,000-word essay on anti-trust laws just can't match.

- The technology caught up. The shift from expensive woodcuts to faster, cheaper lithography meant these magazines could be produced in high volume. For the first time, the working class could afford to buy a weekly dose of rebellion for a few cents.

The Dark Side of the Pen

We have to be real here: it wasn't all noble crusading. Gilded Age political cartoons were often incredibly racist and xenophobic. While Nast was a hero for civil rights in many ways, he was also virulently anti-Catholic and often drew Irish immigrants as ape-like thugs. The same visual shorthand used to fight corruption was used to dehumanize people who were "different."

✨ Don't miss: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

This is the nuance people often miss. These artists weren't objective journalists. They were partisans. They were hired guns for magazine publishers who had their own agendas. Sometimes that agenda was "clean up the government." Sometimes it was "keep the 'wrong' people from voting."

The "Standard Oil Octopus" and the War on Trusts

If Nast was the king of the mid-century, the turn of the century belonged to the trust-busters. This is where the imagery gets really creative. You start seeing the rise of the "industrial monster."

One of the most iconic images from this period is Udo Keppler’s (Joseph’s son) depiction of the Standard Oil Company. It’s an octopus. Its tentacles are wrapped around the U.S. Capitol, the statehouse, and its "eyes" are fixed on the White House. This image did more to galvanize the public against John D. Rockefeller than almost any legal filing by the Department of Justice.

It portrayed the corporation as a biological entity—a parasite. It wasn't just a business that was too big; it was a predator. This shifted the conversation from "is this good for the economy?" to "how do we kill the monster?"

🔗 Read more: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

The Impact on Public Policy

Did these cartoons actually change laws? Sort of. They didn't write the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, but they created the political climate that made it impossible for Congress not to pass it. Politicians are, by nature, allergic to being the butt of a joke that everyone is laughing at. When a cartoonist like Bernhard Gillam drew James G. Blaine as the "Tattooed Man"—covered in the names of various scandals—it stuck. Blaine lost the presidency in 1884 in part because he couldn't scrub those "tattoos" off his reputation in the eyes of the voters.

How to Read a Gilded Age Cartoon Today

If you’re looking at these in a museum or an archive, you’ve gotta look for the "Easter eggs." These guys were the masters of the hidden detail.

- Check the labels. In the 19th century, they loved labeling everything. If there's a rock in the background, it probably says "Civil Service Reform" on it.

- Look at the scale. If one person is giant and everyone else is small, the artist is making a point about power imbalances, not just physical size.

- The background matters. Often, the funniest or most biting commentary is happening in the "nosebleed seats" of the drawing—a small figure in the corner doing something hypocritical.

It’s actually kinda funny how little has changed. We still use the donkey and the elephant. We still use the "bloated rich guy" trope. We just do it on Twitter now with 280 characters and a GIF. The medium shifted from ink and stone to pixels and light, but the human desire to mock the powerful is exactly the same as it was in 1880.

Your Gilded Age Deep Dive: What Next?

If you're actually interested in seeing how these images shaped America, don't just look at them on a phone screen. They were meant to be large, tactile, and shared.

- Visit the Library of Congress Online Archives. They have high-resolution scans of Puck and Judge. Looking at the original colors of a Keppler lithograph is a totally different experience than seeing a black-and-white reprint.

- Track a single symbol. Pick one—like the "Labor" figure or the "Columbia" personification—and see how different artists used her to argue for or against things like women's suffrage or workers' rights.

- Compare and Contrast. Take a modern editorial cartoon from the Washington Post and put it next to a Nast. You’ll be shocked at how many of the "visual metaphors" are identical.

The Gilded Age was a time of "glittering on the outside, corrupt on the inside." The cartoonists were the ones who took a hammer to that gold plating to show everyone the rot underneath. They proved that sometimes, a well-placed caricature is more powerful than a thousand laws. If you want to understand why American politics is so visual and so aggressive today, you have to start with the ink-stained rebels of the 19th century.