Gene Pitney was the "Rockin' Chair" of 1960s pop. High-pitched. Melodramatic. Totally unique. But if you look at the history of Gene Pitney It Hurts to Be in Love, you’re looking at a piece of music history that was almost a Neil Sedaka track. Honestly, it’s one of those weird industry accidents that ended up defining a career. Pitney had this incredible, piercing tenor that could make a grocery list sound like a Shakespearean tragedy, and this song was the perfect vehicle for that specific brand of agony.

It’s 1964. The British Invasion is basically flattening everything in its path. Most American solo artists are shaking in their boots because the Beatles and the Stones are sucking up all the oxygen in the room. Then comes Pitney. He didn't look like a rebel. He looked like a guy who’d help you fix a flat tire. But when he opened his mouth to sing about the crushing weight of romance, people stopped. They listened.

The Neil Sedaka Connection and a Studio Gamble

Here’s the thing most people get wrong about this track. It wasn't written for Gene. The song was penned by Howard Greenfield and Helen Miller. Originally, Neil Sedaka recorded the whole thing. He did the vocals, the backing track was set—it was ready to go. But Sedaka was in a bit of a dispute with his label, RCA Victor, because he wanted to move toward a different sound. RCA wouldn't let him release the song on a different label, so the "master" sat there, instrumental and lonely.

Enter Gene Pitney’s team.

They bought the backing track. That’s why the song has that driving, polished Brill Building sound that was Sedaka’s hallmark. Pitney just walked into the studio and layered his vocals over it. It was a hand-me-down that fit like a tailored suit. You can hear the urgency in his voice. It’s a desperate performance. While Sedaka might have made it sound bouncy and "teen-pop," Pitney made it sound like his soul was being ripped out through his ribs. That’s the Pitney magic. He specialized in "the hurt."

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Why the 1964 Soundscape Mattered

Context is everything. In '64, the charts were a mess of genres. You had the Motown machine starting to roar, the surf rock of the Beach Boys, and the fuzzy guitars coming from London. Gene Pitney It Hurts to Be in Love managed to bridge the gap between the old-school crooner era and the high-production pop of the mid-sixties.

The song hit number 7 on the Billboard Hot 100. It stayed on the charts for months.

Why? Because it’s relatable. Everyone has had that moment where being in love feels less like a bouquet of roses and more like a chronic back ache. It’s heavy. Pitney’s voice captures the literal physical sensation of heartache. When he hits those high notes on the chorus—it hurts to be in love—it’s not just a lyric. It’s a confession.

Breaking Down the Musicality

Musically, the song is a masterclass in tension and release. It starts with that insistent drum beat and the piano riff that feels like a ticking clock. There’s no long intro. No fluff. We get straight to the point.

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

- The Verses: Pitney keeps it relatively restrained here. He’s telling a story. He’s setting the scene. He talks about how people think he’s lucky, but he’s actually miserable. It’s the classic "tears of a clown" trope but stripped of the circus vibe.

- The Bridge: This is where the pressure builds. The orchestration swells. You can hear the influence of the Wall of Sound, even though it’s not a Phil Spector production.

- The Chorus: This is the explosion. Pitney’s voice climbs into that stratosphere that few male singers of the era dared to touch. It’s thin, it’s sharp, and it’s haunting.

Some critics at the time thought Pitney was too "theatrical." They called him "The Rockville Rocket" (he was from Connecticut) and dismissed him as a teen idol. But listen to the control. Listen to the way he handles the vowel sounds. That’s not a teen idol. That’s a vocalist who understands the mechanics of emotional delivery.

The Legacy of the "Silver Fox" of Heartbreak

Gene Pitney didn't just sing songs; he wrote them too. He wrote "He's a Rebel" for the Crystals and "Hello Mary Lou" for Ricky Nelson. He knew how a song was built. This gave him an edge when interpreting other people's work like Gene Pitney It Hurts to Be in Love. He wasn't just a "voice for hire." He was a technician.

Interestingly, Pitney had more longevity in the UK than in the US. The Brits loved his eccentricity. They loved the fact that he didn't quite fit the mold of a traditional rock star. While American audiences eventually moved on to psychedelic rock and harder sounds, Pitney remained a staple of the international touring circuit until his death in 2006. He actually died while on tour in Wales, right after a show. He was a performer to the very last second.

What Modern Listeners Often Miss

If you listen to the track today on Spotify or a remastered vinyl, you might notice how "dry" the vocals are compared to modern pop. There’s no Auto-Tune. There’s very little reverb to hide behind. Every crack in his voice, every sharp intake of breath—it’s all there.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

That’s why it feels "human."

In a world of perfectly quantized beats and pitch-corrected vocals, Pitney sounds like a guy standing in a room screaming his truth. It’s messy. It’s a bit over-the-top. But it’s real. That’s the secret sauce of Gene Pitney It Hurts to Be in Love. It’s the sound of a man who has clearly spent some time staring at a ceiling at 3:00 AM wondering where it all went wrong.

The Misconception of the "Easy" 60s

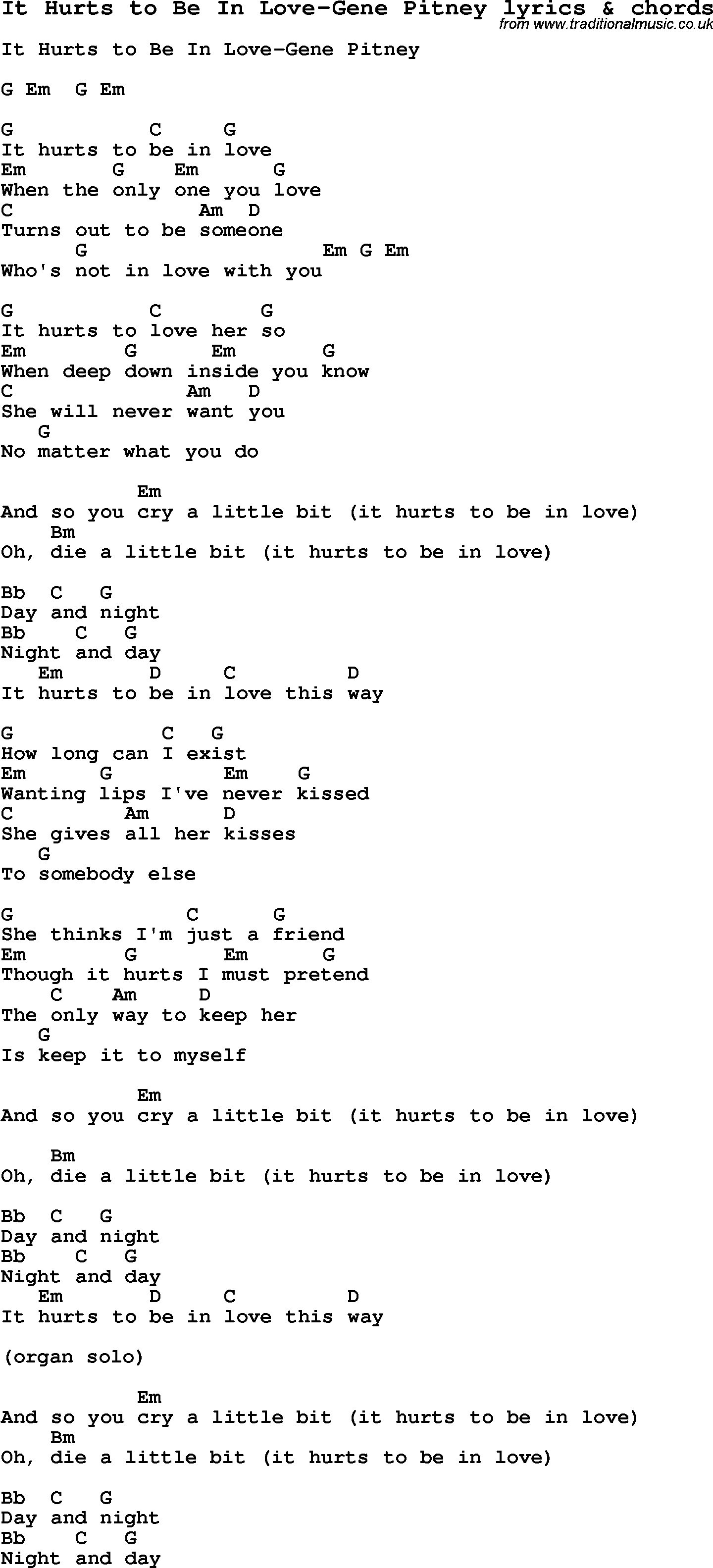

There’s this weird idea that 1960s pop was "simple." People think it was all "moon/june" rhymes and basic chords. "It Hurts to Be in Love" proves that’s nonsense. The chord progression is actually quite sophisticated. It moves through different emotional registers, shifting from a minor-key feel in the verses to a triumphant—yet still painful—major key in the chorus. It’s a psychological trick. It makes you feel the "high" of love and the "low" of the pain simultaneously.

Basically, it's a complicated song dressed up as a three-minute pop radio hit.

Actionable Steps for Music Lovers and Collectors

If you’re looking to truly appreciate this era of music, don’t just stop at the greatest hits. There’s a world of depth here.

- Seek out the mono mix. If you can find the original mono 45rpm or a mono LP, listen to it. The stereo mixes of the 60s often panned the vocals hard to one side, which ruins the impact. The mono mix hits you right in the chest.

- Compare the "Gene Pitney It Hurts to Be in Love" version to Neil Sedaka’s later recordings. Sedaka eventually did release his own versions of the song later in his career. Comparing them is a lesson in how much an artist's "DNA" changes a song. Sedaka is polished; Pitney is raw.

- Explore Pitney's songwriting credits. Check out his work for other artists. It gives you a much better perspective on why he chose the songs he chose to perform.

- Listen for the "Wrecking Crew" influence. While this was a New York Brill Building production, the session musicians of that era were the unsung heroes. The tight, punchy percussion is what keeps the song from becoming a slow ballad.

Gene Pitney was a bridge between eras. He had the dramatic flair of a 1950s opera singer and the pop sensibilities of a modern star. When you hear that opening piano line of "It Hurts to Be in Love," you aren't just hearing a song from 1964. You’re hearing a masterclass in how to turn personal agony into a chart-topping anthem. It’s a reminder that while styles change and technology evolves, the feeling of a broken heart remains exactly the same. It still hurts. And we still want to sing about it.