You’ve heard the sitar. That buzzy, hypnotic opening that feels like a trip to the Far East but was actually recorded in a studio in the American South. It’s the sound of Games People Play by Joe South, a song that hit the airwaves in late 1968 and hasn't really left our collective consciousness since.

Honestly, the track is a bit of an anomaly. It doesn't sound like a typical protest song, yet it’s one of the most searing indictments of human behavior ever to win a Grammy. It’s catchy. It’s soulful. It’s deeply cynical.

Joe South wasn't some newcomer when he released this. He was a seasoned session pro who had already played guitar on Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde and Simon & Garfunkel’s Sounds of Silence. He even provided that iconic, low-tuned tremolo intro for Aretha Franklin’s "Chain of Fools." But when he stepped up to the mic for his own debut album, Introspect, he had something specific to say about the mess the world was in.

The Psychological Roots of the Lyrics

The title isn't just a clever phrase South dreamt up while staring at the ceiling. It was actually inspired by Dr. Eric Berne’s 1964 bestseller, Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships. Berne was a psychiatrist who explored "transactional analysis"—basically, the idea that people interact through scripted, subconscious "games" to avoid real intimacy or to manipulate one another.

South took that clinical concept and dragged it through the red clay of Georgia.

💡 You might also like: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

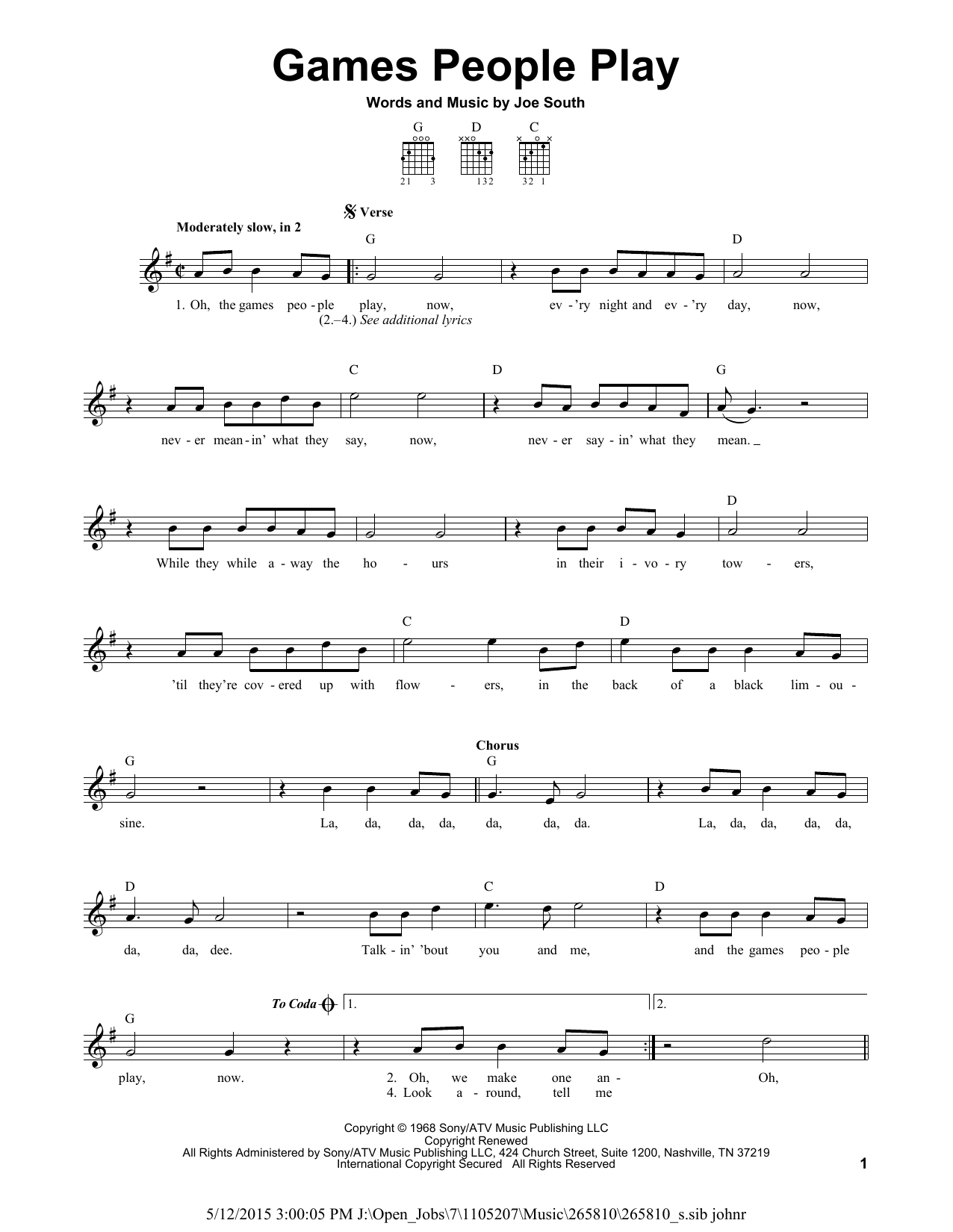

The lyrics aren't about board games. They’re about the "games" of religious hypocrisy, racial prejudice, and social climbing. When he sings about people "never meaning what they say now" or "talking 'bout you and me and the games we play," he’s calling out the phoniness of a society that preaches love while practicing hate. It’s a heavy message wrapped in a "soul-country" package that went all the way to No. 12 on the Billboard Hot 100.

That Electric Sitar Sound

If you want to know why this song stood out in 1969, look no further than the Danelectro Coral Electric Sitar.

While George Harrison was using a traditional Indian sitar to give The Beatles a psychedelic edge, Joe South used the electric version to create a gritty, rhythmic hook. It gave the track a "swampy" feel that bridged the gap between the counterculture and the mainstream.

It was experimental but accessible.

📖 Related: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

The production on the single was actually quite dense for the time. You have the sitar, a driving organ, brass sections, and backing vocals from "The Believers"—which included Joe’s brother Tommy South and his wife Barbara. The song has this building momentum, a sort of rhythmic agitation that mirrors the frustration in the lyrics.

Grammy Glory and the Aftermath

People often forget how big of a deal this song was at the 1970 Grammy Awards. South walked away with Song of the Year and Best Contemporary Song. He beat out massive hits like "Spinning Wheel" and "Raindrops Keep Fallin' on My Head."

It was a peak moment. But success with "Games People Play" was a bit of a double-edged sword for South.

He was a private, somewhat prickly guy who didn't necessarily love the spotlight. The industry wanted more hits, and while he delivered—writing the massive "(I Never Promised You A) Rose Garden" for Lynn Anderson—his personal life began to fray. When his brother Tommy committed suicide in 1971, Joe South largely retreated from the music business, struggling with drugs and the weight of his own introspection.

👉 See also: Tim Dillon: I'm Your Mother Explained (Simply)

Who Else Played the Game?

The song's longevity is proven by how many people have covered it. It’s been recorded by over 100 different artists.

- Freddy Weller took it to the top of the Country charts almost immediately.

- The Inner Circle gave it a reggae makeover in the 90s that became a global hit.

- Waylon Jennings, Della Reese, and even The Tremeloes have had a go at it.

Each version brings out a different flavor, but the core truth of the lyrics remains the same. Whether it’s played as a country ballad or a reggae dance track, the "la-da-da-da-da" chorus still feels like a weary shrug at the state of humanity.

Why It Hits Different in 2026

We live in an era of "curated" lives. Social media is essentially one giant digital version of the games Joe South was singing about sixty years ago. We still have the "ivory towers," and we still have people "covered up with flowers" (or filters) while ignoring the reality underneath.

The song asks for serenity "to remember who I am." That’s a pretty profound request for a pop song. It suggests that the biggest danger of playing these social games isn't just hurting others; it's losing your own identity in the process.

Essential Insights for Collectors

If you're looking to dive deeper into Joe South's work, don't stop at the greatest hits.

- Seek out the Mono 45: Serious audiophiles swear by the original mono single version of "Games People Play." It has a different vocal take and a punchier mix than the common stereo version found on the LP.

- Listen to Introspect: This album is a masterpiece of "Southern Gothic" pop. Tracks like "Mirror of Your Mind" and "Rose Garden" (his own version) show a writer who was way ahead of his time.

- Check the Credits: Once you start looking for Joe South’s name in the liner notes of 60s classics, you’ll see him everywhere. He was the secret weapon of the Atlanta and Muscle Shoals recording scenes.

Actionable Next Steps:

To truly appreciate the craftsmanship, listen to the original Joe South version back-to-back with the Lynn Anderson or Inner Circle covers. Pay attention to how the "sitar hook" changes the mood of the lyrics. Afterward, explore his follow-up "Walk a Mile in My Shoes" to see how he continued his streak of socially conscious songwriting before his semi-retirement from the industry.