If you look at a plant cell under a microscope, you can’t miss it. It’s that massive, clear-ish blob sitting right in the middle, pushing everything else—the nucleus, the mitochondria, the chloroplasts—to the edges like they’re an afterthought. That’s the central vacuole. Honestly, it’s easy to look at it and just think "big empty space," but that couldn't be further from the truth.

The function of the vacuole in a plant cell is basically the difference between a crisp, upright sunflower and a sad, wilted mess on the floor. It isn't just a storage locker; it’s a hydraulic press, a trash compactor, and a chemical defense system all rolled into one.

The Physics of Turgor Pressure (Or Why Plants Don’t Need Bones)

Most people don't realize that plants are basically under high pressure at all times. Think about a tire. When it’s full of air, it’s rigid. When it’s flat, it’s useless. The central vacuole does the same thing for plants using water. This is called turgor pressure.

When a plant is healthy, the vacuole absorbs water through osmosis. It swells up and presses against the cell wall. This creates an internal pressure that keeps the cell stiff. You’ve probably seen what happens when you forget to water your peace lily for three days. It droops. Why? Because the vacuoles are shrinking. They lose that internal pressure, the cell walls lose their support, and the whole structure collapses.

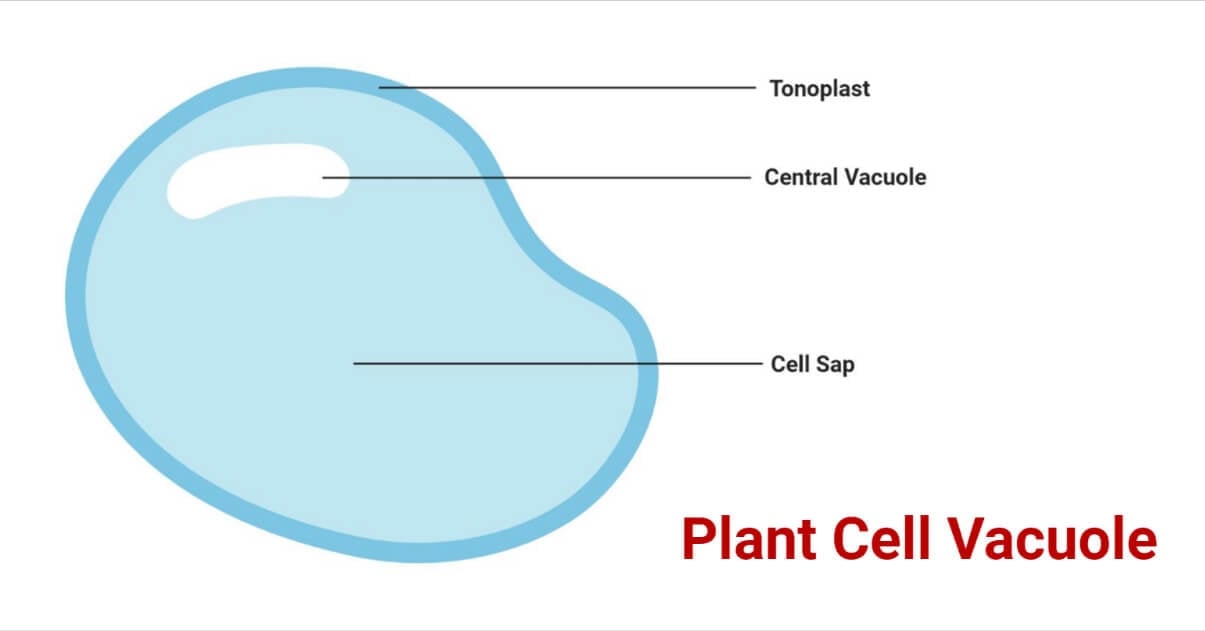

Biologist Dr. Adrienne Roeder at Cornell University has done fascinating work on how cell growth and pressure are regulated. It’s not just about drinking water; it’s about the vacuole maintaining a precise balance. If the pressure is too low, the plant wilts. If the vacuole didn't have a membrane—called the tonoplast—to regulate this, the cell would just pop or shrivel. It’s a delicate dance of solutes and solvents.

👉 See also: Doom on the MacBook Touch Bar: Why We Keep Porting 90s Games to Tiny OLED Strips

It’s a Cellular Warehouse and a Toxic Shield

Storing water is just the start. The vacuole is where the plant hides its "stuff." This includes nutrients like proteins and sugars, but it also includes the nasty stuff. Plants can’t run away from a bug that wants to eat them. They can’t bite back. So, they use chemistry.

Many plants store bitter tannins or even toxic chemicals inside the vacuole. When a herbivore bites into a leaf, the vacuole breaks, releasing these compounds. It's a "stay away" sign written in bitter flavors or actual poison.

- Pigmentation: Ever wonder why some flowers are bright purple or red? Those pigments (anthocyanins) are often stored right there in the vacuole.

- Waste Management: Unlike us, plants don't have a complex excretory system. They use the vacuole to sequester metabolic waste products that might otherwise interfere with the cell’s machinery.

- Seed Germination: In seeds, specialized vacuoles (protein bodies) store the proteins that the baby plant needs to grow before it can start photosynthesizing.

Basically, the vacuole is the most versatile organelle in the plant's toolkit. It’s remarkably efficient.

The Tonoplast: The Gatekeeper You’ve Never Heard Of

We need to talk about the tonoplast. That’s the membrane surrounding the vacuole. If the vacuole is the room, the tonoplast is the high-security door. It’s packed with proton pumps.

✨ Don't miss: I Forgot My iPhone Passcode: How to Unlock iPhone Screen Lock Without Losing Your Mind

By pumping hydrogen ions into the vacuole, the tonoplast keeps the interior acidic. This acidity is crucial for breaking down large molecules. In this way, the vacuole acts a lot like a lysosome in an animal cell—it’s a recycling center. It breaks down old proteins and organelles that aren't working anymore. It's "autophagy," which is a fancy way of saying the cell eats its own junk to stay clean.

The Function of the Vacuole in a Plant Cell vs. Animal Cells

A common mistake is thinking animal cells have the same kind of vacuole. They don't. Animals have tiny, temporary vacuoles used for transport. Plants are the ones that went "all in" on the giant central version.

Why? Because animals have skeletons. We have bones or shells to hold us up. Plants use the vacuole for structural integrity. Also, plants are stuck in one spot. They have to deal with whatever the environment throws at them—floods, droughts, or a hungry goat. Having a massive reservoir to store water and toxins is a survival necessity for a stationary organism.

What Happens When the Vacuole Fails?

When the function of the vacuole in a plant cell is compromised, the plant dies. Period. This can happen through "plasmolysis." If you put a plant in soil that’s too salty, the water gets sucked out of the vacuole and into the soil. The vacuole shrinks so much that the cell membrane actually pulls away from the cell wall. It’s a gruesome way for a cell to go.

🔗 Read more: 20 Divided by 21: Why This Decimal Is Weirder Than You Think

This is why "over-fertilizing" can actually kill your plants. You’re essentially creating an environment where the vacuole can’t do its job of holding onto water.

Real-World Nuance: It’s Not Just One Big Bag

While we usually talk about "the" central vacuole, some cells have multiple vacuoles that eventually fuse together as the cell matures. In very young, meristematic cells (the ones that are actively dividing), you might see several smaller vacuoles. As the cell grows and specializes, these merge into the giant one we see in textbooks.

It’s also worth noting that the size of the vacuole can change rapidly. It’s a dynamic organelle. It’s constantly expanding and contracting based on the plant's needs and the time of day. Some plants even use their vacuoles to help manage their "internal clock" or circadian rhythms by shifting ions back and forth.

Actionable Insights for Plant Health

Understanding vacuole function isn't just for biology tests; it’s practical for anyone growing anything.

- Monitor Turgor Daily: Don't wait for total wilt. Slight softening of leaves means the vacuoles are starting to lose pressure. Water then to avoid permanent cell damage.

- Watch the Salt: Avoid heavy synthetic fertilizers that build up salts in the soil. High salt concentrations interfere with the vacuole’s ability to draw in water via osmosis.

- Humidity Matters: In dry air, plants lose water faster than the vacuoles can keep up, leading to "leaf tip burn" where the cells at the furthest reaches of the plant's hydraulic system give up first.

- pH Balance: Since the tonoplast relies on ion exchange, keeping your soil pH in the correct range for your specific plant ensures that the vacuole can maintain its internal acidity and nutrient storage capabilities.

By respecting the hydraulic and storage needs of the central vacuole, you're directly supporting the primary mechanism that keeps a plant upright and healthy. It's the engine of plant life, hidden in plain sight.