Imagine standing in a quiet forest in Oregon in 1945. The war feels a million miles away, restricted to newsreels and ration books. Then, you find a pile of silk and paper. You touch it. Suddenly, everything explodes. This isn’t a hypothetical movie scene. It actually happened. The Japanese Fu Go balloon bombs were the world’s first intercontinental weapon system, a desperate, brilliant, and terrifyingly low-tech attempt to set the American West on fire from five thousand miles away.

History books usually ignore this. They talk about the Blitz, the Manhattan Project, or the heavy lifting in the Pacific. But the Fu Go balloon bombs represent a weird, fascinating intersection of meteorology and desperation. Japan knew they couldn't outbuild the U.S. industrial machine. They couldn't send a fleet of bombers across the Pacific without them getting shredded. So, they looked at the sky. They looked at the Jet Stream, a high-altitude wind current that scientists like Wasaburo Oishi had been studying long before the West really grasped its power.

It was a gamble. A massive, high-altitude gamble.

The Science Behind the Fu Go Balloon Bombs

The technical engineering here is honestly kind of wild when you consider the materials. We aren't talking about titanium or advanced composites. These were basically giant spheres made of washi paper—hand-crafted from mulberry bushes—glued together with potato flour paste. Some were made of rubberized silk, but the paper ones were the real workhorses. They were about 33 feet in diameter. Think about that. A three-story building made of paper, floating at 30,000 feet.

How do you keep a paper balloon at a specific altitude for three days while it crosses the largest ocean on Earth? You build a "logic" circuit out of gravity and altimeters.

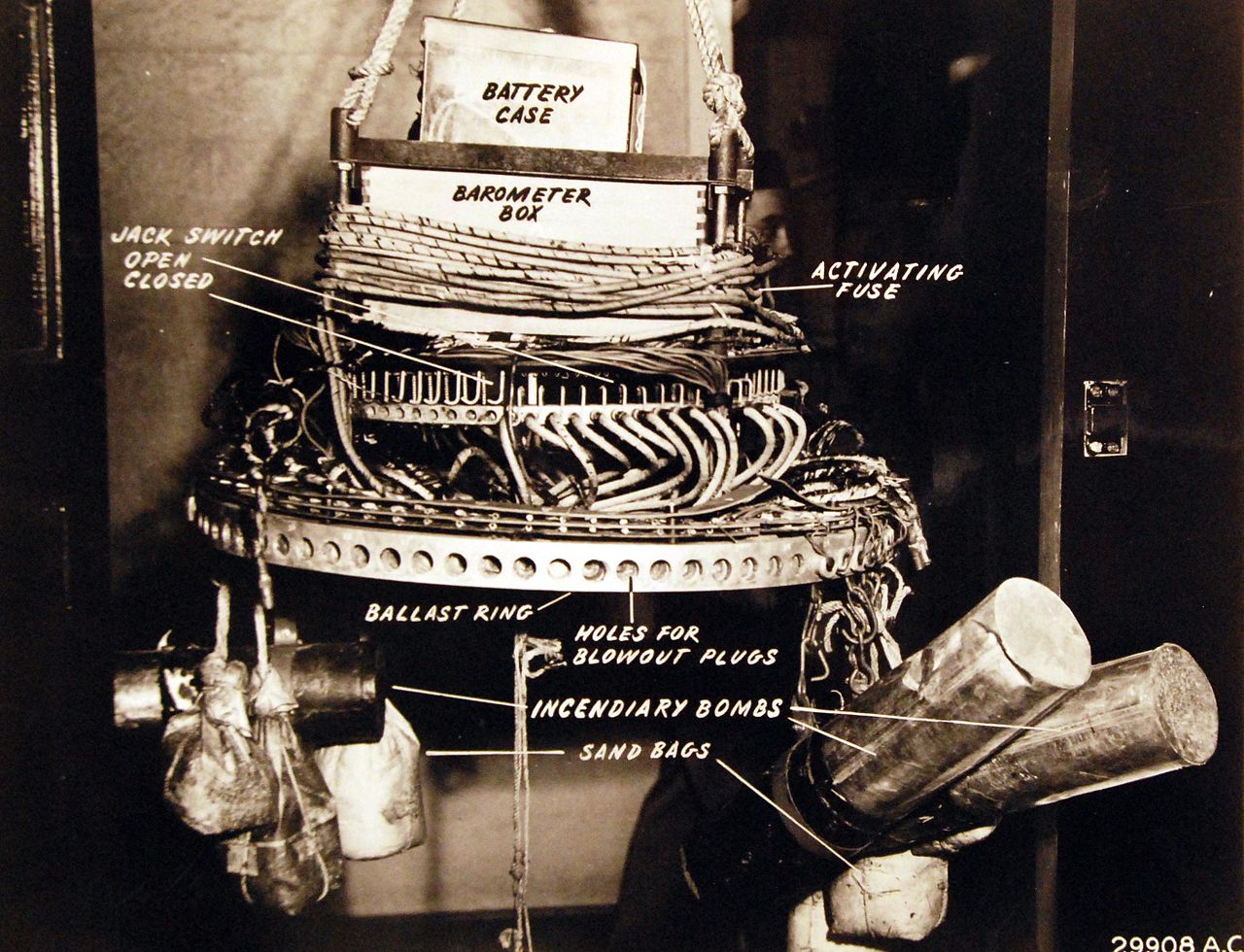

Japanese engineers, led by the Military Scientific Research Institute, developed an ingenious ballast system. If the balloon dropped below 30,000 feet, an altimeter would trigger a small electric charge, dropping a sandbag. If it got too high, a valve would vent hydrogen. This see-sawed the balloon across the Pacific. Once the ballast ran out—meaning it had presumably reached the U.S. mainland—the final release would drop the incendiary bombs and a high-explosive charge.

The goal wasn't just to kill people. It was to cause chaos. They wanted to burn down the massive forests of the Pacific Northwest, forcing the U.S. to divert thousands of troops to fight fires instead of fighting in the Pacific. It was psychological warfare as much as it was physical.

✨ Don't miss: Uncle Bob Clean Architecture: Why Your Project Is Probably a Mess (And How to Fix It)

The Secret Attack on North America

Between November 1944 and April 1945, Japan launched about 9,000 of these things. It sounds like a lot. It is a lot. But the Pacific is huge. Most of them splashed down in the ocean or popped in the upper atmosphere. However, at least 300 made it to land.

They showed up everywhere. People found remnants in Alaska, California, Arizona, and even as far east as Michigan and Iowa. One even drifted into Mexico and another into Canada. Most did nothing. They sat in the dirt, silent and forgotten, until a hiker or a farmer stumbled upon them.

But on May 5, 1945, the tragedy hit home.

In Bly, Oregon, Reverend Archie Mitchell took his pregnant wife, Elsie, and five Sunday school students on a picnic near Gearhart Mountain. While Archie was parking the car, the others found a strange object in the woods. They yelled back to him that they’d found a balloon. Archie shouted a warning, but it was too late. The bomb detonated. Elsie and all five children—Dick Patzke, Joan Patzke, Edward Engen, Jay Gifford, and Sherman Shoemaker—were killed instantly. They were the only casualties of the war on the U.S. mainland caused by enemy action.

It’s a heavy story. It also highlights why the U.S. government went into a total media blackout.

Why You Never Heard About It

The Office of Censorship took a massive risk. They told newspapers and radio stations: Do not mention the balloons. They didn't want Japan to know the bombs were reaching the target. If Japan thought the mission was a failure, they’d stop launching them. If they knew they were hitting Oregon or Michigan, they might have scaled up or, even worse, started attaching biological weapons. There was a very real fear that the Fu Go balloon bombs could be used to spread anthrax or the plague.

🔗 Read more: Lake House Computer Password: Why Your Vacation Rental Security is Probably Broken

The blackout worked.

The Japanese military, hearing nothing in the American press, assumed the balloons were falling into the sea. General Kusaba, who oversaw the project, shut it down in April 1945 because he thought it was a complete waste of resources. The silence of the American media literally saved lives by convincing the enemy they were failing.

But there was a dark side to this silence. Because the public wasn't warned, the Mitchell party had no idea what they were looking at. Had the government issued a public warning, that tragedy in Bly might have been avoided. It’s one of those impossible ethical dilemmas of wartime.

The Modern Risk: Are They Still Out There?

Here is the part that usually weirds people out. The Japanese launched 9,000. We found maybe 300. That leaves a whole lot of unexploded ordnance potentially sitting in the remote wilderness of the Pacific Northwest or the Canadian Rockies.

The materials—paper and silk—biodegrade. But the metal components? The high explosives? Those don't just go away. They become more unstable over time. In 1955, a balloon bomb was found near Edson, Alberta. In 2014, a military bomb disposal team had to detonate a remnant found by forestry workers in Lumby, British Columbia.

It's not just a history lesson. It's a lingering, albeit small, public safety concern.

💡 You might also like: How to Access Hotspot on iPhone: What Most People Get Wrong

How the Fu Go Changed Warfare

While the Fu Go balloon bombs didn't win the war or burn down the forests, they proved a concept. They proved that you could hit a continent from the other side of the world using the environment as a delivery vehicle.

It was a precursor to the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), just moving at 100 miles per hour instead of Mach 20. It showed that the "moat" of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans wasn't impenetrable anymore. Technology had bridged the gap, even if that technology was just paper and sand.

Today, we look at high-altitude surveillance balloons—like the ones that made headlines in early 2023—and we see the DNA of the Fu Go. The principle remains the same: use the upper atmosphere to bypass traditional defenses.

What to Do If You Find Something Strange in the Woods

If you’re hiking in the backcountry of the West Coast or Canada and you see something that looks like vintage machinery, rusted metal rings, or bundles of weathered cordage, don't be a hero.

- Don't touch it. This seems obvious, but curiosity is a powerful thing. Old explosives are "sweating" explosives, meaning the chemicals have separated and become incredibly sensitive to friction.

- Mark the location. Use your GPS or a flagging tape, but stay at least 100 yards away once you’ve identified it.

- Call the authorities. Contact the local police or Forest Service. They have protocols for dealing with UXO (Unexploded Ordnance) and will bring in military EOD teams if necessary.

- Educate others. If you live in an area where these have been found historically (like Southern Oregon or British Columbia), make sure kids know that "old junk" in the woods can be dangerous.

The Fu Go balloon bombs remain a haunting reminder of a time when the world was so desperate that even the wind was weaponized. Understanding them isn't just about trivia; it's about acknowledging the reach of global conflict and the strange, ingenious, and tragic ways humans try to overcome the vastness of our planet.

To dig deeper into this, you can visit the Oregon Historical Society, which maintains records and artifacts related to the Bly explosion, or check out the National Museum of the United States Air Force, which houses one of the few remaining balloon envelopes. These sites provide the best primary source evidence for just how close this "paper' threat came to changing the American home front.