Most people think they know Frances Hodgson Burnett. They’ve seen the 1993 film version of The Secret Garden with that hauntingly beautiful scenery, or maybe they remember a dusty copy of A Little Princess sitting on a grandmother's shelf. But honestly? The real world of Frances Hodgson Burnett books is way weirder, darker, and more obsessed with cold hard cash than the Disneyfied versions suggest.

She was a powerhouse. A total workaholic.

Burnett wasn't just writing "sweet stories" for kids; she was a woman who basically invented the modern celebrity author lifestyle, moving between grand estates in England and luxury apartments in New York, all while churning out prose to keep her family afloat. She wrote over fifty books and hundreds of short stories. Yet, we usually only talk about three of them.

The rags-to-riches reality behind the fiction

Burnett didn’t start at the top. Not even close. After her father died in Manchester, her family moved to Tennessee in 1865, right into the chaotic aftermath of the American Civil War. They were broke. Like, "gathering wild grapes to sell so they could buy postage stamps" broke. That desperation is the engine behind almost all Frances Hodgson Burnett books. When you read about Sara Crewe losing everything in A Little Princess, you aren't just reading a fairy tale. You’re reading Burnett’s own memories of what it feels like to have the floor fall out from under your life.

She sold her first story to Godey’s Lady’s Book when she was just eighteen. She was so worried the editors would think she was only writing for money—which she was—that she famously stated she was doing it for "the sake of the family."

The "Big Three" and why they actually work

It is impossible to discuss her legacy without hitting the heavy hitters. But let's look at them through a slightly more cynical, adult lens for a second.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886)

This book was a massive, global phenomenon. Think Harry Potter levels of hype. It’s the story of Cedric Errol, a kid from New York who finds out he’s the heir to a British earldom. It’s basically a "fish out of water" story where the fish is wearing velvet and lace. Fun fact: this book single-handedly doomed an entire generation of boys to wearing "Fauntleroy suits"—velvet jackets and wide lace collars. They hated it. The book is often dismissed now as being too sugary, but if you look closer, it’s a sharp critique of the British class system and the coldness of the aristocracy.

A Little Princess (1905)

This one is the ultimate "survival" book. Sara Crewe is a "rich girl" who becomes a servant at her own boarding school when her father dies penniless. What’s fascinating here is Sara’s mental toughness. She uses storytelling as a literal weapon against her environment. It’s sort of a psychological manual on how to keep your dignity when the world treats you like dirt.

The Secret Garden (1911)

This is the masterpiece. Period. Mary Lennox is a "disagreeable" child—Burnett’s words—who is sent to a gloomy mansion in Yorkshire. The genius of this book isn't just the garden; it's the fact that Burnett was one of the first mainstream writers to explore the "mind-body connection." She was heavily influenced by New Thought and Christian Science at the time, believing that positive thinking and nature could physically cure illness. Whether or not you buy into the mysticism, the portrayal of two lonely, angry children healing each other is objectively incredible writing.

The stuff you’ve probably never heard of

Burnett wrote for adults. A lot.

In fact, she considered herself a serious novelist for grown-ups, and books like Through One Administration or The Shuttle were huge sellers in their day. The Shuttle is particularly interesting because it deals with "International Marriages"—rich American heiresses marrying broke British aristocrats for their titles. It’s basically Downton Abbey but written while it was actually happening, and with a lot more bite.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

Then there is The Making of a Marchioness. It starts out as a somewhat standard Cinderella story about a plain, older woman named Emily Fox-Seton who works as a sort of "lady's assistant." But then, in the second half (often published as The Methods of Lady Walderhurst), it turns into a straight-up Gothic thriller involving attempted murder and a plot to steal an inheritance. It’s wild.

Why people keep coming back

There is a specific "Burnett vibe." It’s a mix of extreme comfort—warm fires, hot tea, thick blankets—and extreme peril. She understood that for a happy ending to feel earned, the "middle" has to feel genuinely hopeless.

Her prose isn't minimalist. She loves adjectives. She loves describing the exact texture of a silk dress or the smell of a damp moor. You can practically taste the "thick, rich milk" and "hot oatcakes" she describes. This sensory overload is why Frances Hodgson Burnett books are the ultimate "comfort reads" for adults today. We live in a digital, sterile world; Burnett gives us dirt, gardens, and velvet.

The complicated bits (The "Expert" View)

We have to be honest: some of her work hasn't aged perfectly. Because she was a product of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, there are moments of colonialism and classism that can make a modern reader cringe. In The Secret Garden, Mary Lennox’s initial descriptions of India and the people there are... not great.

However, scholars like Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina (who wrote an excellent biography on Burnett) point out that she was often more progressive than her peers. She portrayed Mary as a girl with agency—a girl who didn't need a prince to save her, just a shovel and some seeds.

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

How to actually read her today

If you want to move beyond the basics, don't just grab the first Penguin Classic you see.

- Start with the 1905 version of A Little Princess. It’s much more developed than the shorter 1888 version titled Sara Crewe.

- Read "The Shuttle." It’s long, but it’s the best way to understand how she viewed the power struggle between "New Money" America and "Old World" England.

- Check out her short stories. "The Land of the Blue Flower" is a weird, allegorical fable that shows her more spiritual, philosophical side.

The sheer volume of Frances Hodgson Burnett books means there is always something "new" to find. She was a woman who lived through the death of her eldest son, two messy divorces, and a constant barrage of tabloid gossip, yet she never stopped writing about the possibility of transformation.

That’s the hook.

Transformation.

The idea that a dead garden can bloom, that a beggar can be a princess, and that even the most "disagreeable" person can find a way to be loved. It's a hopeful, gritty kind of magic that doesn't rely on wands or spells, just resilience and maybe a little bit of gardening.

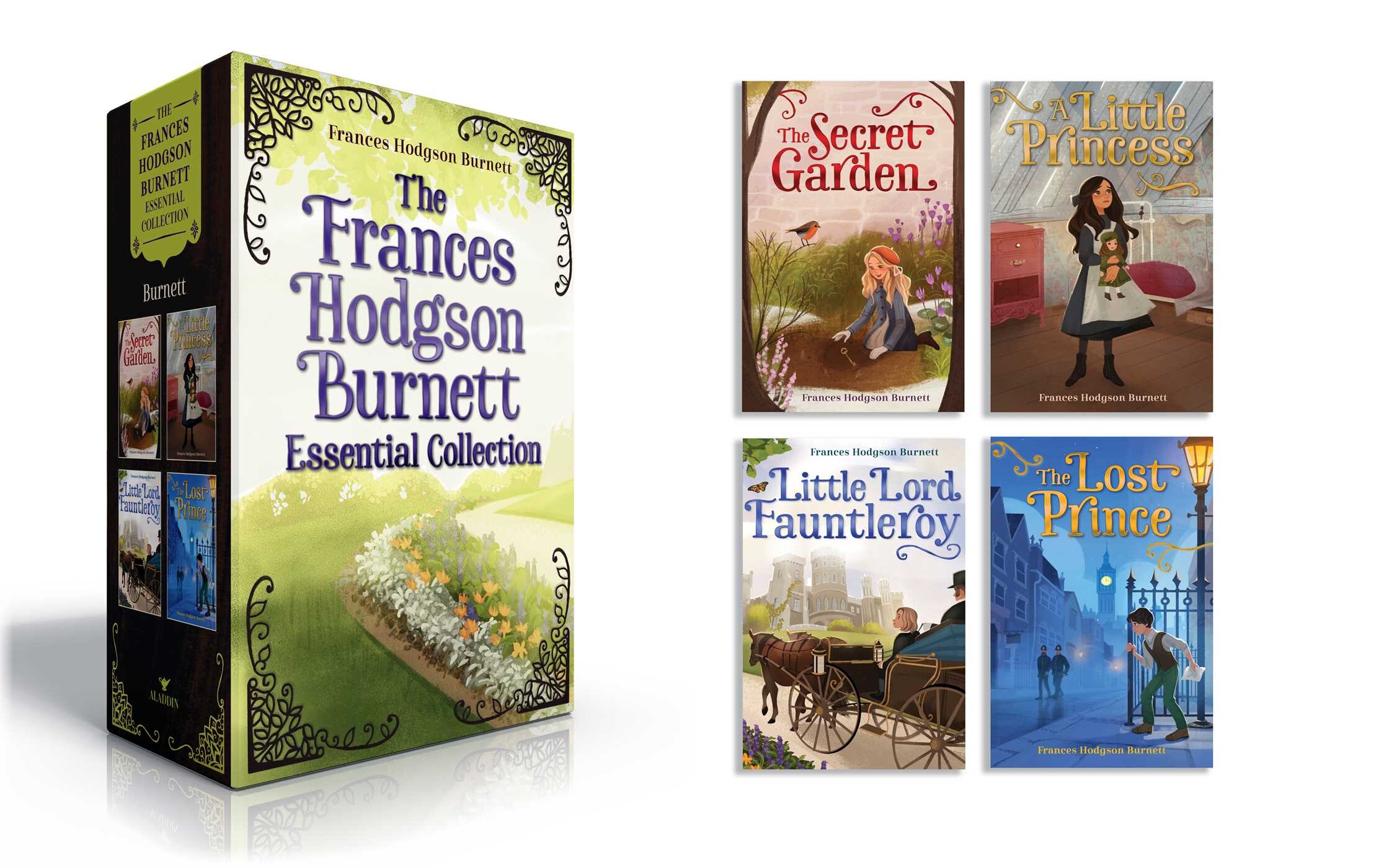

Taking Action: Building your Burnett collection

Forget the mass-market paperbacks. If you want the real experience, look for older editions with illustrations by Tasha Tudor or Charles Robinson. The visual element was always a huge part of how these stories were consumed.

Next, compare The Secret Garden to The Lost Prince. You’ll see the same themes—lonely boys, secret missions, and the power of the mind—but set against a backdrop of European political intrigue. It’s a completely different flavor but the same expert craftsmanship. Digging into her bibliography is like finding a hidden door in a wall you've walked past a thousand times. Once you go through, the world looks a lot more interesting.