If you walked into a theater in 1973 expecting a standard gothic horror flick, you were in for a massive, bloody shock. Flesh for Frankenstein isn't your grandfather’s Universal monster movie. Honestly, it’s barely even a "Frankenstein" movie in the traditional sense. Produced by Andy Warhol and directed by Paul Morrissey, this film is a gooey, campy, and strangely philosophical piece of cult cinema that remains just as divisive today as it was fifty years ago.

It’s gross. It’s funny. It’s surprisingly beautiful in a way that only 70s Technicolor can manage.

The movie, originally released as Il mostro è in tavola... barone Frankenstein in Italy, was filmed in Space-Vision 3D. This wasn't the polished, digital 3D we see in modern blockbusters. This was the kind of 3D that involved poking internal organs directly at the camera lens on the end of a long pole. If you’ve seen it, you know exactly which scenes I’m talking about. If you haven’t, well, prepare yourself for some of the most literal "in-your-face" gore ever captured on celluloid.

The Warhol Connection and Paul Morrissey’s Vision

People often call it "Andy Warhol's Frankenstein," but Warhol’s actual involvement was mostly just letting his name be used for marketing. It was Paul Morrissey who did the heavy lifting. Morrissey wanted to subvert everything. He took the basic tropes of Mary Shelley’s novel and twisted them into a critique of aristocracy, sex, and the sheer arrogance of the ruling class.

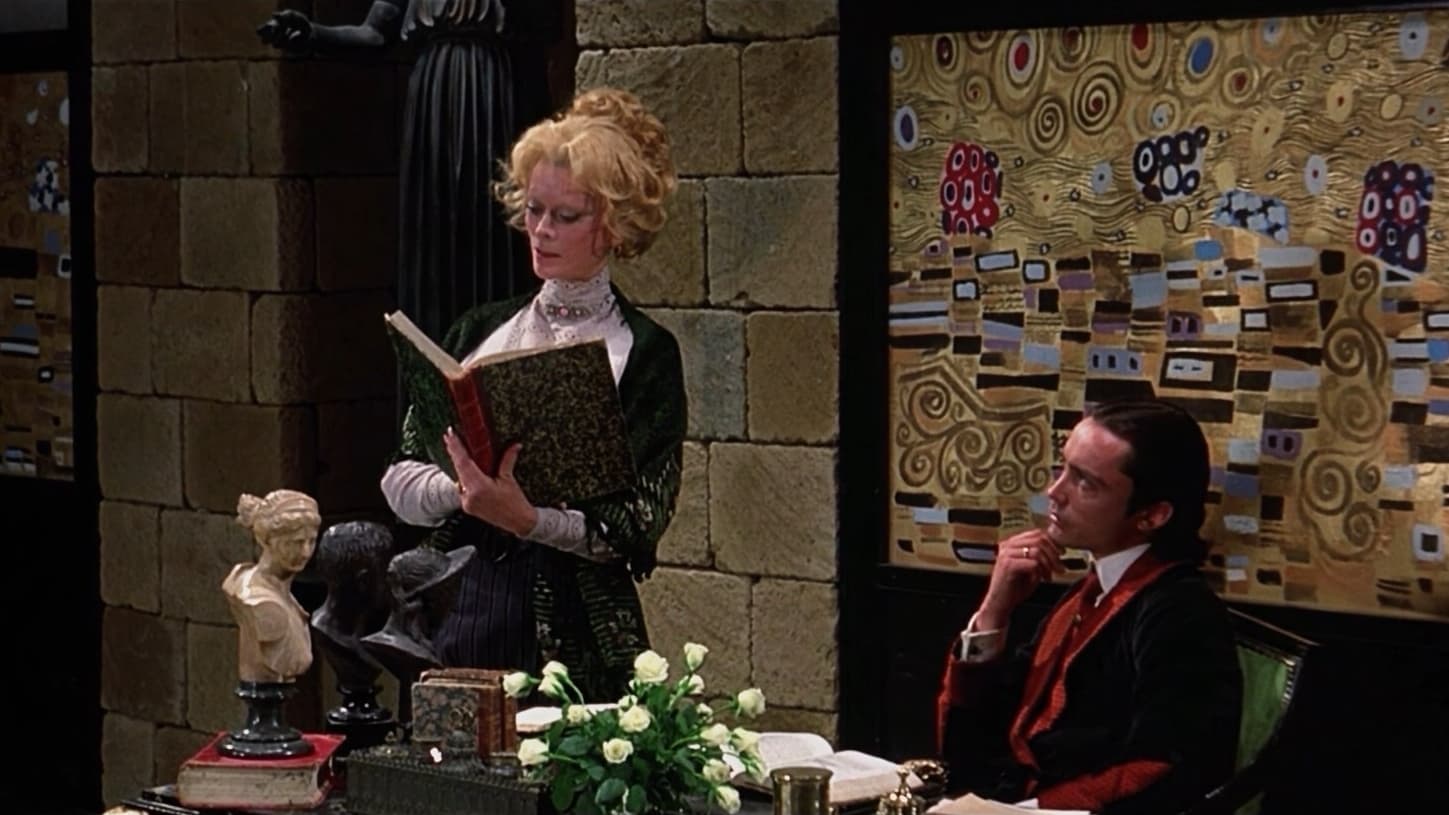

Udo Kier plays Baron von Frankenstein.

He is, quite frankly, incredible. Kier brings this frantic, high-pitched intensity to the role that makes you wonder if he’s about to have a heart attack or an orgasm—sometimes both at once. His Baron isn't trying to benefit humanity. He’s obsessed with creating a "superior" Serbian race. It’s deeply uncomfortable and intentionally transgressive.

The plot is basically a fever dream. The Baron is trying to build two perfect beings (a male and a female) to breed a new master race. The problem? He keeps picking the wrong heads. He thinks he’s grabbed the head of a sexually voracious stud for his male creation, but he actually ends up with a monk-in-training who has taken a vow of celibacy. This leads to some of the most bizarrely comedic "failed" sex scenes in cinema history.

Blood, Guts, and 3D Organs

The gore in Flesh for Frankenstein is legendary. It’s not "scary" gore, though. It’s bright, wet, and theatrical. Carlo Rambaldi, the man who would later create the animatronics for E.T. and the xenomorph head effects in Alien, handled the special effects here.

The juxtaposition is wild.

One minute you’re looking at a beautifully composed shot of a European villa, and the next, Udo Kier is elbow-deep in a torso, lecturing his assistant about the beauty of a gallbladder. The 3D gimmick was used ruthlessly. Morrissey famously said he wanted to use 3D because "the only thing people want to see in 3D is things being stuck into them."

Why the Tone Confuses People

Is it a comedy? Yes. Is it a horror movie? Also yes.

Most viewers struggle with the tone because it refuses to settle down. It’s played with a deadpan seriousness by Kier, while Joe Dallesandro (the "Warhol Superstar") plays the hero with a thick New York accent that feels wildly out of place in 18th-century Europe. It’s jarring. It’s supposed to be. Dallesandro represents a sort of raw, animalistic reality that disrupts the Baron’s cold, intellectual fantasies.

Then there’s the eroticism. The film was rated X or heavily censored in many countries upon release. It treats the human body like a collection of parts—meat to be rearranged. There’s a coldness to the sexuality that mirrors the Baron’s own detachment from life.

The Lasting Legacy of the Flesh for Frankenstein Movie

You can see the DNA of this movie in everything from The Rocky Horror Picture Show to the body horror of David Cronenberg. It pushed the boundaries of what "art-house" cinema could be by blending it with "grindhouse" sensibilities.

It’s a movie about the failure of perfection.

The Baron’s creations are physically perfect but spiritually empty or fundamentally broken. It’s a cynical take on the Enlightenment. The idea that we can use science to conquer nature is presented as a literal bloody mess.

🔗 Read more: Limp Bizkit - Behind Blue Eyes: What Really Happened with the Most Hated Cover of 2003

If you’re looking for a deep, emotional connection to a monster, go watch the 1931 Boris Karloff version. If you want a movie that feels like a decadent, drug-fueled party where someone happens to be performing surgery in the middle of the dance floor, Flesh for Frankenstein is your go-to.

Practical Tips for First-Time Viewers

If you're going to dive into this, don't watch a low-quality stream. The cinematography by Luigi Kuveiller is actually quite stunning, and a grainy bootleg ruins the effect of the saturated colors. Look for the 4K restoration by Vinegar Syndrome. They did a massive job cleaning up the negatives, and it includes the 3D version if you have the gear for it.

- Watch for the subtext: Pay attention to how the Baron talks about "the state" and "reproduction." It’s a scathing satire of fascist ideology.

- Check out the companion piece: Morrissey and Kier filmed Blood for Dracula immediately after this with much of the same cast. It’s a great double feature.

- Keep an open mind: The acting is "heightened." Don't mistake the camp for bad acting; it’s a very specific aesthetic choice.

The movie ends exactly how you think it would—in a total bloodbath where nobody really wins. It’s messy, it’s arrogant, and it’s undeniably unique.

To truly appreciate what Morrissey was doing, you have to accept that the movie hates its own characters. It invites you to laugh at their demise while simultaneously being grossed out by the viscera. It’s a tough balancing act that few films have managed to replicate since.

Next Steps for the Cinephile:

- Seek out the 4K restoration: The colors are essential to the experience.

- Compare the "Warhol" duo: Watch Flesh for Frankenstein back-to-back with Blood for Dracula to see how Kier and Dallesandro flip their character dynamics.

- Read up on Carlo Rambaldi: Seeing his early work here explains a lot about the tactile nature of his later Hollywood effects.

- Listen to the score: Claudio Gizzi’s music is surprisingly lush and romantic, which makes the on-screen carnage even funnier.