Richard Adams wasn't trying to write a cute story about bunnies. If you’ve actually sat down with the 400-plus pages of the 1972 classic, you know it’s closer to The Odyssey or The Aeneid than it is to Peter Rabbit. And at the absolute center of this bloody, dirt-under-the-fingernails epic is Fiver from Watership Down.

He’s tiny. He’s twitchy. Honestly, most of the other rabbits in the Sandleford Warren think he’s just a "nutcase." But Fiver—or Hrairoo in the Lapine language—is the reason any of them survive at all. He is the catalyst. Without his shivering fits and his visions of a field "covered with blood," the story never starts. Every single rabbit would have been gassed in their holes by land developers.

It’s weirdly relatable. We live in a world that’s constantly telling us we’re overreacting to things, but Fiver is the ultimate proof that sometimes the "crazy" person in the room is the only one actually paying attention. He represents the survival value of extreme sensitivity.

The Burden of Being Right

Fiver isn't a prophet because he wants to be. It’s a curse. In the opening chapters, his distress isn't some mystical, glowing-eyed trance; it’s a physical, agonizing panic attack. He sees the notice board placed by humans at the edge of the warren, and though he can't read the English words, he feels the impending doom of the "Thousand" (the enemies of rabbits).

The psychological depth here is staggering for a book often filed in the children’s section. Adams portrays Fiver’s second sight as a heavy, exhausting weight. Think about it. You’re the smallest guy in the room, everyone thinks you’re a liability, and you’re trying to convince the "Threarah" (the Chief Rabbit) that the entire world is about to end. It’s a lonely place to be.

Hazel, Fiver’s brother, is the only one who really listens. That relationship is the emotional spine of the book. Hazel isn't the visionary; he’s the leader who knows how to translate Fiver’s raw, terrifying intuition into a plan of action. It’s a perfect partnership. Fiver provides the "why," and Hazel provides the "how."

The Reality of Rabbit Vision

When people talk about Fiver from Watership Down, they often get caught up in the "magic" of it. But if you look at the biology, rabbits are high-strung by design. They are prey animals. Their entire existence is a series of calculated risks and sensory inputs.

👉 See also: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Adams, who was a civil servant before he was a world-famous novelist, spent a massive amount of time studying R.M. Lockley’s The Private Life of the Rabbit. He wanted the behavior to be grounded in reality. Fiver is basically a biological alarm system turned up to eleven. While the other rabbits are grazing and thinking about the present, Fiver is tuned into the subtle shifts in the environment that signal a total systemic collapse.

- He senses the "wire" (snares) before they see them.

- He feels the presence of the Black Rabbit of Inlé (the rabbit grim reaper).

- He identifies the wrongness of Cowslip’s Warren—a place where rabbits are fed by humans only to be harvested for meat.

That Cowslip’s Warren sequence is probably the most chilling part of the book. The rabbits there are healthy, huge, and "artistic," but they’ve traded their survival instincts for security. Fiver is the only one who smells the rot. He screams at Hazel that the roof of the burrow is made of bones. He’s not being literal, but he’s spiritually accurate. That’s the core of his character: he sees the truth behind the appearance of safety.

Why Fiver Isn't Just a "Victim"

It’s easy to dismiss Fiver as the weakling. He’s small. He can’t fight. He doesn’t have the muscle of Bigwig or the cleverness of Blackberry. But as the journey progresses toward the titular Watership Down, Fiver’s status shifts.

He becomes the moral and spiritual compass.

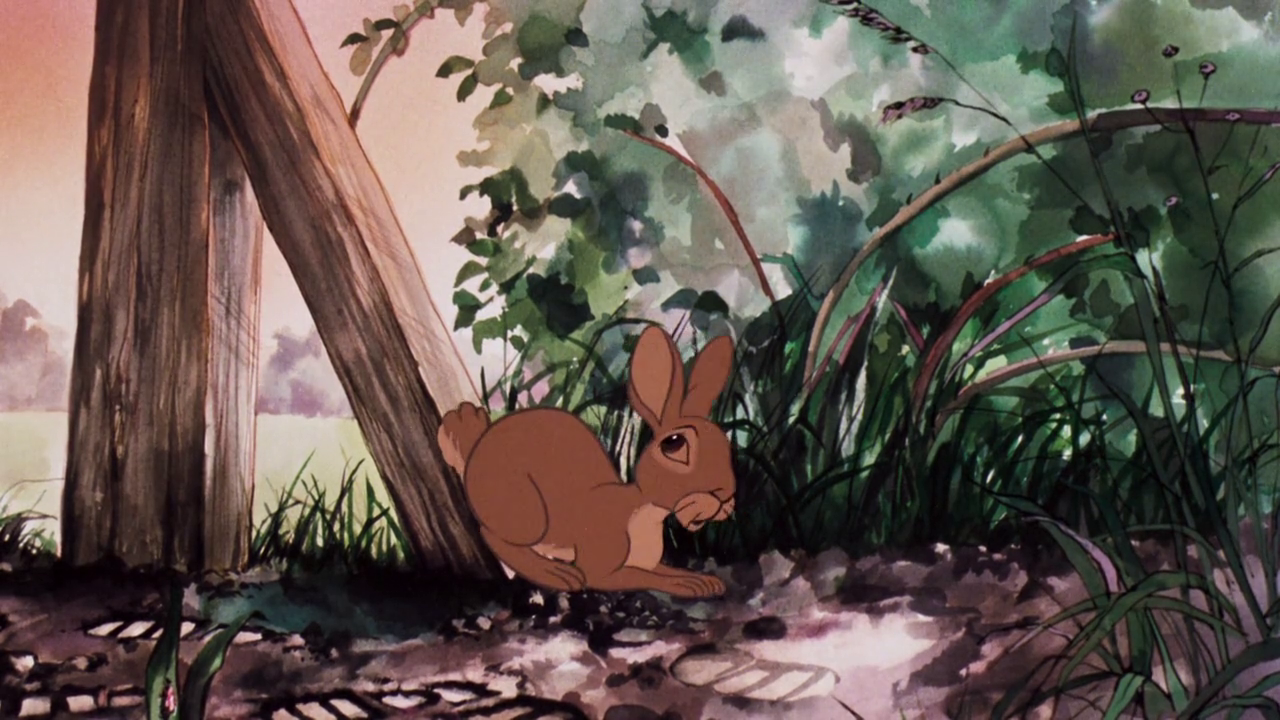

There’s a moment after the escape from Efrafa where the rabbits are exhausted and broken. General Woundwort—basically the rabbit version of a dictator—is coming for them. The situation is objectively hopeless. In the 1978 animated film, this is depicted with haunting, psychedelic imagery, but in the book, it’s more subtle. Fiver goes into a trance and essentially "dreams" the solution, leading Hazel to the idea of releasing the farm dog.

He’s a "shaman" in the truest sense. In many ancient cultures, the person who was "different" or suffered from "fits" wasn't cast out; they were made the spiritual leader. Adams taps into that archetype perfectly. Fiver is the bridge between the physical world of the hedgerow and the mythological world of El-ahrairah (the Great Rabbit Trickster).

✨ Don't miss: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

The Contrast with General Woundwort

If Fiver is the extreme of sensitivity, General Woundwort is the extreme of "strength." Woundwort is a fascinating villain because he’s not "evil" in a cartoonish way; he’s a rabbit who decided that the only way to survive is to become more dangerous than the predators. He creates a police state. He bans wandering. He silences dissent.

Woundwort represents total control. Fiver represents total vulnerability.

The irony? Woundwort’s "strength" eventually leads to the destruction of his warren because he can’t conceive of a threat he can’t bite. Fiver’s "weakness" leads to a new home because he’s willing to listen to the things that scare him. It’s a powerful message about the different types of courage. It takes one kind of courage to fight a cat; it takes another kind to tell your friends they need to leave everything they know because you have a bad feeling in your gut.

Modern Interpretations: Neurodivergence and Fiver

Looking at the character through a 2026 lens, many readers see Fiver from Watership Down as an early representation of neurodivergence or high-functioning anxiety. He processes sensory information differently than his peers. What they see as a quiet field, he sees as a tapestry of potential outcomes.

He’s often overwhelmed. He needs space. He needs a "translator" like Hazel. But he’s also indispensable. There’s a growing realization in modern psychology that "anxiety" isn't always a disorder; sometimes it’s an overactive survival mechanism that was incredibly useful when humans were still living in caves. Fiver is that ancient survival mechanism in rabbit form.

How to Apply "The Fiver Mindset" Without Losing Your Mind

You probably aren't a rabbit, and you probably aren't worried about being gassed in a hole. But the lessons from Fiver’s character are actually pretty practical if you strip away the Lapine mythology.

🔗 Read more: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

First, stop apologizing for your intuition. We are trained to look for "data" and "logic" for every decision. But intuition is often just your brain processing thousands of tiny data points that haven't quite reached your conscious mind yet. When Fiver says "something is wrong," he’s reacting to real, if subtle, stimuli.

Second, find your Hazel. If you’re a "Fiver"—someone who is highly sensitive or visionary but perhaps lacks the "muscle" to execute—you need a partner who respects your insight but can handle the logistics.

Third, recognize the "Cowslip Warrens" in your own life. These are the situations that look perfect on the outside—maybe a high-paying job or a stable relationship—but require you to ignore your instincts or suppress your true nature to stay. Fiver knew that a comfortable life in a snare isn't a life at all.

Key Takeaways from Fiver’s Journey

- Sensitivity is a survival trait. Don't let a "tough" culture convince you that being observant or cautious is a flaw.

- Trust the "shiver." If your gut says a situation is "blood-red," pay attention to the environment. Look for the "notice board" you might be missing.

- Find a community that values your specific "gift." The Sandleford Warren failed because it ignored its visionaries. Watership Down succeeded because it integrated them.

Next time you find yourself feeling "twitchy" about a big life decision, remember Fiver from Watership Down. He wasn't crazy; he was just the only one who could see the future coming. Being the first to see the danger is a lonely job, but it’s the only way the rest of the group makes it through the night.

To really understand the nuance of this character, re-read the "Nuthanger Farm" chapters. Pay attention to how Fiver reacts when Hazel is wounded. He doesn't panic then; he becomes a pillar of quiet, desperate certainty. It turns out that when the real crisis hits, the person who has been "panicking" their whole life is often the calmest one in the room. They’ve already lived through the disaster a thousand times in their head. They’re ready.